Hong Kong Med J 2015 Feb;21(1):5–9 | Epub 2 Jan 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144376

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Disease spectrum and treatment patterns in a local male infertility clinic

KL Ho, FRCSEd (Urol), FHKAM (Surgery); James HL Tsu, FRCSEd (Urol), FHKAM (Surgery); PC Tam, FRCSEd (Urol), FHKAM (Surgery); MK Yiu, FRCS (Edin), FHKAM (Surgery)

Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, The University of Hong Kong,

Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KL Ho (hokwanlun@gmail.com)

Abstract

Objective: To review disease spectrum and

treatment patterns in a local male infertility clinic.

Design: Case series.

Setting: Male infertility clinic in a teaching hospital

in Hong Kong.

Patients: Patients who were seen as new cases in

a local male infertility clinic between January 2008

and December 2012.

Intervention: Infertility assessment and counselling

on treatment options.

Main outcome measures: Disease spectrum and

treatment patterns.

Results: A total of 387 new patients were assessed

in the male infertility clinic. The mean age of the

patients and their female partners was 37.2 and

32.1 years, respectively. The median duration of

infertility was 3 years. Among the patients, 36.2%

had azoospermia, 8.0% had congenital absence

of vas deferens, and 48.3% of patients had other

abnormalities in semen parameters. The commonest

causes of male infertility were unknown (idiopathic),

clinically significant varicoceles, congenital absence

of vas deferens, mumps after puberty, and erectile or

ejaculatory dysfunction. Overall, 66.1% of patients

chose assisted reproductive treatment and 12.4% of

patients preferred surgical correction of reversible

male infertility conditions. Altogether 36.7% of

patients required either surgical sperm retrieval or

correction of male infertility conditions.

Conclusions: The present study provided important

local data on the disease spectrum and treatment

patterns in a male infertility clinic. The incidences of

azoospermia and congenital absence of vas deferens

were much higher than those reported in the

contemporary literature. A significant proportion of

patients required either surgical sperm retrieval or

correction of reversible male infertility conditions.

New knowledge added by this

study

- The present study provided important local data on the disease spectrum and treatment patterns in a male infertility clinic.

- The incidences of azoospermia and congenital absence of vas deferens in the present study were much higher than those reported in the contemporary literature.

- The present study may help to increase public awareness of the contribution of male factors in infertility assessment and treatment.

- The study provides a background for future research into azoospermia and congenital absence of vas deferens in the locality.

Introduction

Infertility is defined by the inability to conceive after

1 year of regular unprotected sexual intercourse, and

it affects 15% of couples worldwide.1 Male factors

contribute to about 50% of infertile couples. Clinically

significant varicocele is present in 40% of infertile

men and is the commonest surgically reversible

condition. As many as 10% to 15% of infertile men

have azoospermia.2 According to the report of the

Council on Human Reproductive Technology in 2012,

male factor infertility contributes to 50% of women

receiving reproductive technology treatment.3 Local

data on male factor infertility, however, have been

scarce. The objective of the present article was to

review the disease spectrum and treatment patterns

in a local male infertility clinic.

Methods

All consecutive new patients seen in a local teaching

hospital (Queen Mary Hospital) male infertility

clinic from January 2008 to December 2012 were

included in this retrospective study. The clinical

records were reviewed and the demographics of the

patients and their female partners, aetiologies of

male factor infertility, semen analyses, and treatment

were analysed.

All patients underwent two separate semen

analyses and hormonal profiles (including morning

serum testosterone, and follicle-stimulating and

luteinising hormones) before being seen in the clinic.

A detailed urological and reproductive history was

taken, followed by a focused physical examination.

The fertility history was ascertained and female

factors of age and gynaecological history

were taken into consideration. Clinical diagnoses

were made and possible aetiologies were postulated

based on the above information. The patients’ semen

results were classified as azoospermia (no sperms

were identified after examination of the post-centrifugation

pellet), abnormal (in concentration,

motility, morphology, or any combination according

to the contemporary World Health Organization

standards4), or normal. The exact analysis of semen

parameters was beyond the scope of the present

study. Patients with azoospermia were classified

clinically as having obstructive (normal-sized testes

and hormonal profiles) and non-obstructive (small

testes and elevated follicle-stimulating hormones)

disorder. Genetic studies, including karyotyping

and Y chromosome microdeletion, were offered to

patients with non-obstructive azoospermia or severe

oligospermia. Only grade 2 (palpable) or 3 (visible)

varicoceles when standing were considered clinically

significant in the assessment. Diagnosis of congenital

absence of vas deferens was made by physical

examination and occasionally supplemented with

transrectal ultrasound for unclear cases. For patients

with a history of mumps after puberty and no other

identifiable causes of male infertility, mumps was

quoted as the main cause. Depending on the clinical

scenarios, the couples were counselled on different

treatment options, including surgical or assisted

reproductive treatments (ART), donor insemination,

adoption, and conservative treatment.

Results

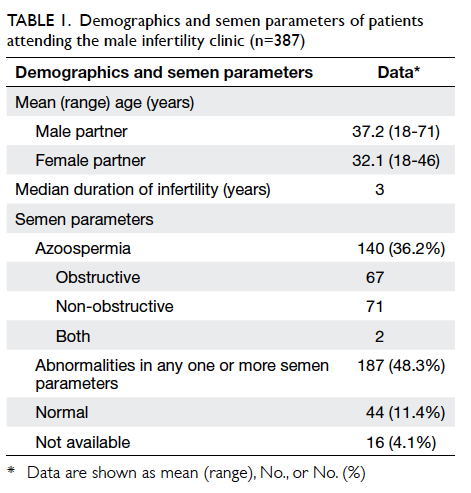

From January 2008 to December 2012, 387 patients

had been seen in the male infertility clinic as new

cases. The mean age of the patients and their female

partners was 37.2 and 32.1 years, respectively. The

median duration of infertility was 3 years. Of the

patients, 140 (36.2%) had azoospermia, of whom 67

and 71 patients had obstructive and non-obstructive

causes, respectively, and two had both components

of azoospermia. A total of 187 (48.3%) patients had

abnormalities in one or more semen parameters

(Table 1).

Table 1. Demographics and semen parameters of patients attending the male infertility clinic (n=387)

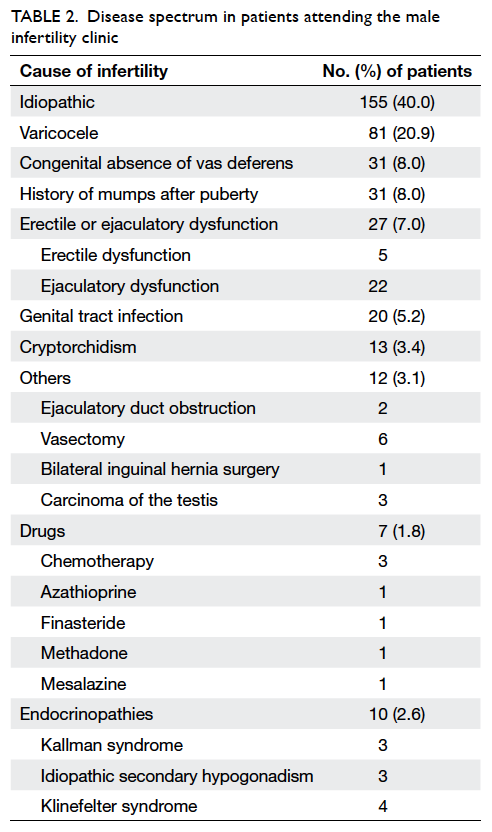

The commonest causes of male factor infertility

were unknown (idiopathic), clinically significant varicoceles,

congenital absence of vas deferens, mumps after

puberty, and erectile or ejaculatory dysfunction

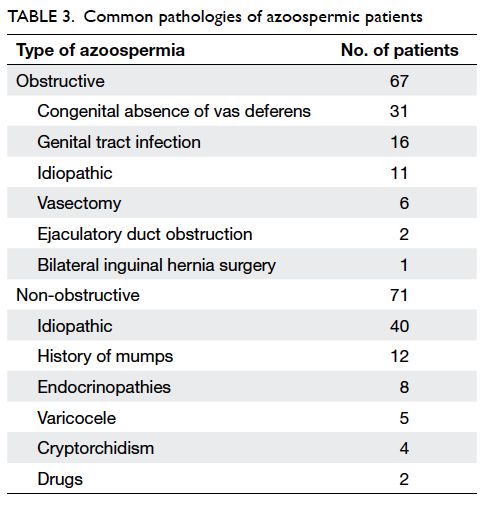

(Table 2). For patients with obstructive azoospermia,

common pathologies included congenital absence of

vas deferens and genital tract infection. For patients

with non-obstructive azoospermia, no causes were

identified in most patients. A history of mumps and

endocrinopathies were implicated in some non-obstructive

azoospermic patients (Table 3).

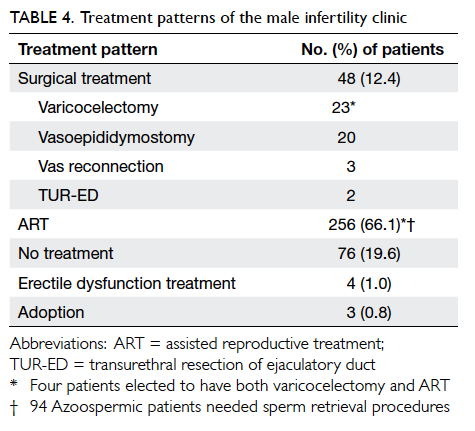

Most patients (66.1%) sought ART. Of these

patients, 94 azoospermic patients (56 patients with

non-obstructive azoospermia, 37 with obstructive

azoospermia, and one with both components)

required sperm retrieval procedures. Besides, 12.4% patients chose surgical treatments for

reversible causes of male infertility. The procedures

included varicocelectomy, vas reconnection, and

vasoepididymostomy. Four patients with varicoceles

and severe oligospermia or azoospermia proceeded

to varicocelectomy and employed ART as backup

treatment. Also, 19.6% patients elected to have

no further treatment of infertility (Table 4).

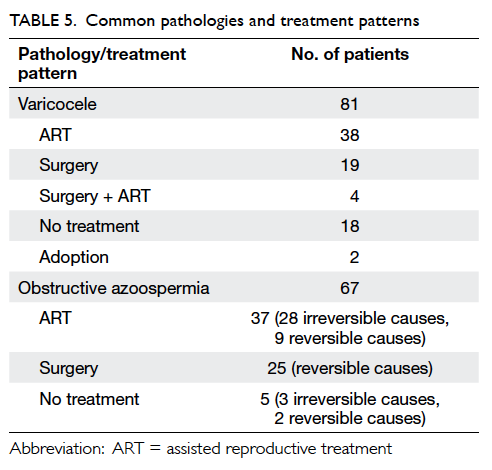

Of 81 patients who had clinically significant

varicoceles and abnormal semen parameters, 23

proceeded to surgery and 38 chose ART. Of 67 patients

who had obstructive azoospermia, 37 proceeded to

ART; 28 of these patients had congenital absence of

vas deferens that was irreversible, requiring sperm

retrieval and ART. For the other patients with

reversible causes of obstructive azoospermia, nine

preferred sperm retrieval and ART, while 25 elected

to have surgical treatments (Table 5).

Discussion

Infertility has remained a worldwide problem in the

past two decades.5 Traditionally, the female partner

has shouldered the major burden of infertility

assessment and treatment. With recent advances

in male infertility treatment6 and increasing public

awareness, there is a growing demand for assessment

and treatment of men with fertility issues.

When the infertility clinic at Queen Mary

Hospital was first established, it consisted of a joint

clinic assessment both by urologists specialising

in male infertility treatment and by gynaecologists

specialising in ART. Due to the long waiting list

at the conjoint clinic, the male infertility clinic

has since separated out. All infertile couples with

clinically suspected male infertility factors—such as

gross abnormalities in semen parameters, or erectile

or ejaculatory dysfunction—are referred to the male

infertility clinic for prompt assessment.

The median duration of infertility in this study

was 3 years before the infertile couples attended

for assessment. Upon referral, a large proportion

(36.2%) of patients had azoospermia. This figure was

much higher than the commonly quoted figures in

the current literature, where azoospermia was found

in 1% of all men and 10% to 15% of infertile men.7 8 9

The much higher figure in the present study was

probably related to referral bias. Male partners with

milder forms of abnormalities in semen parameters

might not have been referred for assessment.

These couples with an azoospermic male partner

would have benefited from earlier intervention

instead of wasting precious time attempting natural

conception. The present study illustrates the importance

of a premarital, or at least a pre-pregnancy,

checkup. Simple semen analysis would have identified

male partners with azoospermia or severe deficits

of semen parameters for early assessment, fertility

treatment, counselling, and potential intervention.

Besides, 11.4% of patients had normal

semen parameters and fell into the category of

unexplained infertility.10 After common female

factors have been ruled out, there are still many

possible causes of infertility, ranging from the

couple’s miscomprehension of the female fertility

window and coital behaviours to abnormal sperm

function.11

Clinically significant varicocele was the

commonest identifiable cause of male infertility

in the present study. This was concurrent with the

contemporary literature.12 Controversies over the

best treatment of varicoceles in infertile couples have

been met with a meta-analysis13 and randomised

controlled trials14 15 favouring surgery in terms of

pregnancy outcomes. Varicocelectomy is offered to

patients according to the criteria of the American

Society for Reproductive Medicine,12 namely,

documented history of infertility, grade 2 or above

varicocele, abnormalities in semen parameters,

and reversible female factors. In our institution,

the microsurgical subinguinal approach is used for

its lower risks of recurrence and hydrocele.16 In the

present study, 38 patients with varicoceles chose

ART, while 23 patients chose surgery. The decision

to proceed to ART versus varicocelectomy was made

after thorough counselling of the involved couples.

Factors considered included the female partner’s age,

semen quality, risks of surgery versus ART, expertise

of the surgeons and ART centre staff, and the

respective treatment outcome audits. Both male and

female partners were strongly encouraged to attend

counselling together and arrive at the decision that is

most agreeable to both parties.

A significant proportion of patients in the study

had azoospermia, of which 47.9% had obstructive

causes. Congenital absence of vas deferens was the

commonest cause of obstructive azoospermia, which

constituted 8.0% of the study population. This was

higher than the 1% to 2% of infertile men reported in

the literature.7 9 The incidence of congenital absence of

vas deferens is not well reported in Chinese men with

infertility. One of the reasons for the high incidence

in this study could be referral bias, which led to a

very high incidence of azoospermia in our study

population. Hence, the proportional percentage of

congenital absence of vas deferens was much higher

than is usually quoted. Sperm retrieval and ART

was offered as the only solutions for childbearing.

In Caucasians, congenital absence of vas deferens

is associated with cystic fibrosis transmembrane

conductance regulator (CFTR) gene mutations of

cystic fibrosis,17 and routine genetic study is offered

to patients and their female partners. Recent data

in Chinese patients with congenital absence of vas

deferens showed different CFTR gene mutations,18

which might lead to the development of a mild

genital form of cystic fibrosis. Cystic fibrosis is very

rare in Asian populations, but genetic counselling

for patients with congenital absence of vas deferens

is still advised by most authorities. Unfortunately,

genetic study is not available at Queen Mary

Hospital, and the huge number of possible CFTR

gene mutations (>1500) makes targeted examination

in Chinese patients a big challenge.

Of 256 patients who proceeded to ART, 94

with azoospermia needed some sort of sperm

retrieval procedures. For patients with congenital

absence of vas deferens and markedly distended

epididymal tubules, percutaneous epididymal sperm

aspiration provided a simple and reliable method

of sperm retrieval. For patients with obstructive

azoospermia secondary to infection or idiopathic

causes, microsurgical epididymal sperm aspiration

was employed to retrieve the maximum number

of sperms with the least blood contamination.

Sometimes extensive adhesiolysis needed to be

performed to expose distended epididymal tubules.

Non-obstructive azoospermia was the most difficult

condition to treat. Conventional testicular sperm

extraction (TESE) involves multiple random testis

biopsies and can fail to find focal seminiferous tubules

harbouring active spermatogenesis. This method

involves excision of more testicular tissues and is

associated with more postoperative intra-testicular

haematoma and scarring.19 Microdissection

TESE (MicroTESE) involves identifying the

spermatogenically active regions of the testes by

direct examination of larger seminiferous tubules

under high magnification.20 This method is targeted

and involves retrieval of the maximum number of

sperms with the least testicular tissue loss. However,

MicroTESE is time-consuming and involves a steep

learning curve.21 Even in the hands of experts, the

procedure takes an average of 1.8 and 2.7 hours for

successful and unsuccessful cases, respectively.

Of 36 patients with reversible causes of

obstructive azoospermia (Table 5), 25 (69.4%)

chose surgical treatment, nine proceeded to ART, and

two preferred conservative treatment. In the era

of ART, surgical treatment remains a valuable

armamentarium in the management of reversible

obstructive azoospermia.1 At Queen Mary Hospital,

microsurgical intussusception vasoepididymostomy

was offered to patients with epididymal obstruction

secondary to infection or idiopathic causes.22 The

choice between surgical treatment and ART was

made after thorough consideration of the female

partner’s age, surgical expertise and ART success

rates, and the infertile couple’s wishes.

Within this study population, 142 (36.7%)

patients needed either surgical sperm retrieval

and ART or surgical correction of reversible male

infertility conditions.

Conclusions

The present study describes the disease spectrum

of a local male infertility clinic. The incidence of

azoospermia and congenital absence of vas deferens

was much higher than that described in the current

literature. There was high demand for sperm

retrieval or surgical correction services in this group

of patients.

References

1. Lee R, Li PS, Schlegel PN, Goldstein M. Reassessing

reconstruction in the management of obstructive

azoospermia: reconstruction or sperm acquisition? Urol

Clin North Am 2008;35:289-301. CrossRef

2. Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive

Medicine in collaboration with Society for Male

Reproduction and Urology. The management of infertility

due to obstructive azoospermia. Fertil Steril 2008;90(5

Suppl):S121-4. CrossRef

3. Infertility diagnosis by age of patients receiving RT

procedures (other than DI and AIH) in 2012. Council on

Human Reproductive Technology. Available from: http://www.chrt.org.hk/english/publications/files/table17_2012.pdf. Accessed Aug 2014.

4. Cooper TG, Noonan E, von Eckardstein S, et al. World

Health Organization reference values for human semen

characteristics. Hum Reprod Update 2010;16:231-45. CrossRef

5. Mascarenhas MN, Flaxman SR, Boerma T, Vanderpoel

S, Stevens GA. National, regional, and global trends in

infertility prevalence since 1990: a systematic analysis of

277 health surveys. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001356. CrossRef

6. Male Infertility Best Practice Policy Committee of the

American Urological Association; Practice Committee of

the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Report

on optimal evaluation of the infertile male. Fertil Steril

2006;86(5 Suppl 1):S202-9. CrossRef

7. Wosnitzer M, Goldstein M, Hardy MP. Review of

azoospermia. Spermatogenesis 2014;4:e28218. CrossRef

8. Berookhim BM, Schlegel PN. Azoospermia due to

spermatogenic failure. Urol Clin North Am 2014;41:97-113. CrossRef

9. Wosnitzer MS, Goldstein M. Obstructive azoospermia.

Urol Clin North Am 2014;41:83-95. CrossRef

10. Hamada A, Esteves SC, Agarwal A. Unexplained male

infertility—looking beyond routine semen analysis. Eur

Urol Rev 2012;7:90-6.

11. Agarwal A, Bragais FM, Sabanegh E. Assessing sperm

function. Urol Clin North Am 2008;35:157-71, vii. CrossRef

12. Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive

Medicine. Report on varicocele and infertility. Fertil Steril

2008;90(5 Suppl):S247-9. CrossRef

13. Marmar JL, Agarwal A, Prabakaran S, et al. Reassessing the

value of varicocelectomy as a treatment for male subfertility

with a new meta-analysis. Fertil Steril 2007;88:639-48. CrossRef

14. Abdel-Meguid TA, Al-Sayyad A, Tayib A, Farsi HM. Does

varicocele repair improve male infertility? An evidence-based

perspective from a randomized, controlled trial. Eur

Urol 2011;59:455-61. CrossRef

15. Mansour Ghanaie M, Asgari SA, Dadrass N, Allahkhah A,

Iran-Pour E, Safarinejad MR. Effects of varicocele repair

on spontaneous first trimester miscarriage: a randomized

clinical trial. Urol J 2012;9:505-13.

16. Leung L, Ho KL, Tam PC, Yiu MK. Subinguinal

microsurgical varicocelectomy for male factor subfertility:

ten-year experience. Hong Kong Med J 2013;19:334-40. CrossRef

17. Esteves SC, Miyaoka R, Agarwal A. Sperm retrieval

techniques for assisted reproduction. Int Braz J Urol

2011;37:570-83. CrossRef

18. Lu S, Yang X, Cui Y, et al. Different cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator mutations in Chinese men with congenital bilateral absence of vas deferens and other acquired obstructive azoospermia. Urology 2013;82:824-8. CrossRef

19. Okada H, Dobashi M, Yamazaki T, et al. Conventional

versus microdissection testicular sperm extraction for

nonobstructive azoospermia. J Urol 2002;168:1063-7. CrossRef

20. Schlegel PN. Testicular sperm extraction: microdissection

improves sperm yield with minimal tissue excision. Hum

Reprod 1999;14:131-5. CrossRef

21. Dabaja AA, Schlegel PN. Microdissection testicular sperm

extraction: an update. Asian J Androl 2013;15:35-9. CrossRef

22. Ho KL, Wong MH, Tam PC. Microsurgical

vasoepididymostomy for obstructive azoospermia. Hong

Kong Med J 2009;15:452-7.

Find HKMJ in MEDLINE: