Hong Kong Med J 2015 Feb;21(1):30–7 | Epub 7 Nov 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134185

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Effectiveness of a new standardised Urinary

Continence Physiotherapy Programme for

community-dwelling older women in Hong Kong

BS Leong, MSc, BScPT1,2; Nicola W Mok, PhD1

1 Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, Hong Kong Polytechnic

University, Hunghom, Hong Kong

2 Elderly Health Service, Department of Health, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Nicola W Mok (nicola.mok@polyu.edu.hk)

Abstract

Objective: To examine the effectiveness of a

standardised Urinary Continence Physiotherapy

Programme for older Chinese women with stress,

urge, or mixed urinary incontinence.

Design: A controlled trial.

Setting: Six elderly community health centres in

Hong Kong.

Participants: A total of 55 women aged over 65

years with mild-to-moderate urinary incontinence.

Interventions: Participants were randomly assigned

to the intervention group (n=27) where they received

eight sessions of Urinary Continence Physiotherapy

Programme for 12 weeks. This group received

education about urinary incontinence, pelvic floor

muscle training with manual palpation and verbal

feedback, and behavioural therapy. The control

group (n=28) was given advice and an educational

pamphlet on urinary incontinence.

Results:

There was significant improvement in

urinary symptoms in the intervention group,

especially in the first 5 weeks. Compared with the

control group, participants receiving the intervention

showed significant reduction in urinary incontinence

episodes per week with a mean difference of -6.4

(95% confidence interval, -8.9 to -3.9; t= –5.3;

P<0.001) and significant improvement of quality of

life with a mean difference of -3.93 (95% confidence

interval, -5.08 to -2.78; t= –6.9; P<0.001) measured

by Incontinence Impact Questionnaire Short Form

modified Chinese (Taiwan) version. The subjective

perception of improvement, measured by an 11-point visual analogue scale, was markedly better

in the intervention group (mean, 8.7; standard

deviation, 1.0; 95% confidence interval, 8.4-9.1) than in the control group (mean, 1.4; standard

deviation, 0.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-1.7;

t=33.9; P<0.001). The mean treatment satisfaction in

the intervention group was 9.5 (standard deviation,

0.8) as measured by an 11-point visual analogue

scale.

Conclusions: This study demonstrated that the

Urinary Continence Physiotherapy Programme was

effective in alleviating urinary symptoms among older Chinese women with mild-to-moderate

heterogeneous urinary incontinence.

New knowledge added by this

study

- This standardised Urinary Continence Physiotherapy Programme is effective in improving various types of urinary incontinence of mild-to-moderate severity.

- The superior exercise compliance and treatment outcome in this study are likely attributed to the palpation and verbal feedback provided by physiotherapists during pelvic floor muscle training.

- A standardised urinary continence programme consisting of education, supervised pelvic floor muscle training with palpation, and behavioural therapy is an effective first-line management for various types of urinary incontinence in a community setting.

Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI), defined as “the

complaint of any involuntary leakage of urine”,1 is

a major clinical problem, and a significant cause of

disability and dependency in the aged population.

It is a condition with heterogeneous pathology and

commonly classified as stress urinary incontinence

(SUI), urge urinary incontinence (UUI), and mixed

urinary incontinence (MUI) depending on the

symptom behaviour. While the prevalence of UI in

older women, globally, is estimated to range from

15% to 30%,2 the reported prevalence rate of UI in

Hong Kong ranges from 20% to 52%.3 It has been

acknowledged that UI is associated with profound

adverse impact on the quality of life (QoL) of the

sufferers.3 4 The impact of UI is so substantial that

community-dwelling elderly with UI reported

inferior physical and mental health, worse self-perceived

health status, greater disability, and more

depressive symptoms.5 In addition, the extent of the

impact was shown to be associated with the severity

of UI. Therefore, it is important to investigate a safe

and effective treatment strategy in this population,

especially in a community setting.

Conservative management has been

recommended as the first-line management for UI.

It is acknowledged that a variety of conservative

management strategies which require patient’s active

participation shows promising results for patients

with UI. These include pelvic floor muscle training

(PFMT),6 7 vaginal cones,8 bladder training (BT),9 and

even combination of PFMT and general lumbopelvic

mobilisation exercises.10 A recent Cochrane review7

suggested that PFMT, the ‘knack’ manoeuvre (a

voluntary counterbracing type of contraction

during physical stress), and BT are effective

strategies in the management of UI in general. In

particular, a combination of PFMT and BT was

shown to have superior outcome than BT alone

for the management of UUI and MUI.9 However,

to date, there is insufficient conclusive evidence

on the best approach for PFMT.11 In addition, the

applicability and effectiveness of PFMT and BT for

treating UI have not been properly evaluated in the

elderly Chinese population, especially in randomised

controlled studies. The aim of this study was to

evaluate the effectiveness of a Urinary Continence

Physiotherapy Programme (UCPP), which is a

comprehensive programme involving education and

exercise (PFMT and BT) components for managing

SUI, UUI, and MUI in older Chinese women in a

community setting.

Methods

A total of 60 subjects were recruited for screening

by convenience sampling from six Elderly Health

Centres (EHCs), Department of Health, Hong Kong.

Inclusion criteria were Chinese females aged 65

years or older who had a clinical diagnosis of SUI,

UUI, or MUI (with reference to the definition from

International Continence Society1) of a mild-to-moderate

severity (based on the scoring system by

Lagro-Janssen et al12) which is made by the EHC

medical officers in-charge. Exclusion criteria were

active urinary tract infection, patients on diuretic

medication, presence of bladder pathology or

dysfunction due to genitourinary fistula, tumour,

pelvic irradiation, neurological or other chronic

conditions (eg diabetes mellitus, Parkinson’s disease),

previous anti-incontinence surgery, significant

cognitive impairment assessed by the Cantonese

version of Mini-Mental State Examination Score

(CMMSE13 with cutoffs of: ≤18 for illiterate

subjects, ≤20 for those who had had 1 to 2 years of

schooling, ≤22 for those who had had more than 2

years of schooling out of a maximum score of 30),

obesity (body mass index [BMI] of >30 kg/m2), and use

of concomitant treatments during the trial.

Randomisation was performed prior to the

study by an off-site investigator using a computerised

randomisation programme with allocation

concealment by sequentially numbered, opaque, and

sealed envelopes. After taking consent, grouping

of the individual participants was revealed to the

principal investigator by phone. Overall, 55 eligible

participants were assigned to the intervention

(n=27) or control (n=28) groups. The trial period

lasted for 12 weeks. The study was approved by the

Institutional Medical Research Ethics Committee

and was conducted in accordance with the

Declaration of Helsinki.14

Intervention protocol

One physiotherapist was responsible for delivering

assessment and treatment to all subjects during the

trial period of 12 weeks, and she was not blinded to

the intervention.

The intervention group received a 30-minute

individual training session at a pre-decided time

of the day, once weekly for the first 4 weeks; and

then once bi-weekly for the remaining 8 weeks. A

total of eight treatment sessions were given to each

recipient. There were three major components in

the UCPP: education (anatomy of the pelvic floor

muscle [PFM] and urinary tract, urinary continence

mechanism, and bladder care), PFMT with the aid

of vaginal palpation, and BT. Pelvic floor muscle

training included Kegel exercise programme

and neuromuscular re-education (the ‘knack’).15

Bladder training involved strategies to increase

the time interval between voids by a combination

of progressive void schedules, urge suppression,

distraction, self-monitoring, and reinforcement.

Four stages of Kegel’s PFMT programme

were adopted in this study, including (1) muscle

awareness, (2) strengthening, (3) endurance, and (4)

habit building and muscle utilisation.16 The exercise

regimen was designed to progressively strengthen

both type I and type II muscle fibres of the pelvic floor.

In the first 2 weeks (muscle awareness phase), one

set of 10 (week 1) and 15 (week 2) slow submaximal

contractions for 5 seconds each and five fast

maximal contractions with a 10-second relaxation

between contractions was performed in lying down

position. In the strengthening phase (weeks 3 to 4),

the muscle-strengthening element was reinforced

by gradually increasing the number of submaximal

contractions to 25 per session with an increment

of five repetitions per week in gravity-dependent

position including sitting and standing. The number

of fast maximal contractions (5) remained the same

as in the awareness phase. In the endurance phase

(weeks 5 to 8), the training was more focused on

improving the performance of slow and sustained

contractions of PFMs by increasing the contraction

time to 10 seconds with submaximal contraction

while keeping the exercise position and number of

both submaximal and maximal contractions as in

week 4. In the habit-building and muscle utilisation

phase (weeks 9 to 12), the learnt neuromuscular

re-education technique (the ‘knack’) and urge

suppression strategies were reinforced. In this period,

one set of 30 slow submaximal contractions for 10

seconds each and 10 fast maximal contractions with

a 10-second relaxation between contractions was

practised. Participants were asked to perform three

sets of the above-mentioned exercise at specific

periods as part of the home programme.

The control group was given advice and received an educational

pamphlet with information about management of UI

at baseline. Participants were given an appointment

for a follow-up visit in 12 weeks.

Outcome measures

A number of indicators were employed to assess

different aspects of outcomes. First, the number

of UI episodes in the previous 7 days (UI7) was

examined using a weekly bladder diary log sheet,

which was also the primary outcome measure of this

study. Information for UI7 was collected at baseline

and then weekly until the end of the programme

(12 weeks). Second, a validated condition-specific

QoL assessment tool—Incontinence Impact

Questionnaire Short Form (IIQ-7) Chinese (Taiwan)

version17—was used to study the impact of UI on

QoL and its change with the intervention after

minor modifications were made to align with the

local culture. Content validation was made by a

panel of doctors who reviewed the instrument

and determined if the questions satisfied the

content domain. Seven items were included in

the questionnaire to examine if the subjects were

suffering from urine leakage under those specific

situations. The questionnaire was administered by

the same physiotherapist and the subjects were asked

to choose the most appropriate response to those 7

items on a 4-point ordinal scale, with 0 meaning

“not at all affected”, 1 “slightly affected”, 2 “moderately

affected”, and 3 “greatly affected”. The maximum score

of 21 indicated a great impact of UI on QoL. Third,

subjective perception of improvement was assessed

with a 10-cm visual analogue scale (VAS) rated from

0 to 10, with 0 suggesting “no improvement” and 10

“complete relief” at the end of the intervention period.

Fourth, another VAS was used to assess subjects’

satisfaction to treatment (on a 0 to 10 rating), with

0 being “totally dissatisfied” and 10 “totally satisfied”.

The IIQ-7 was collected at baseline and at the end

of the programme. Compliance with treatment in

the intervention group was evaluated from two

perspectives: attendance and compliance with home

exercises. Attendance was reviewed by calculating

the proportion of sessions that were attended by

an individual. Compliance with home exercises was

also reviewed by calculating the reported frequency

of exercises being executed. Any drawbacks and

adverse effects during the intervention period were

also monitored.

Statistical analysis

The sample size calculation based on the power

estimation and results of a similar study,18 with a power of 0.8 and α = 0.05 and an attrition rate of 30%, revealed that a recruitment sample of 60

participants (30 participants in each group) was

required. Statistical analysis was performed with the

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Windows

version 13.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US). Any

missing data were treated with “the last observation

carried forward” approach. Independent t tests (for

parametric data) or Mann-Whitney test (for nonparametric

or non-normally distributed data) and

Chi squared tests (for nominal/ordinal data) were

used to compare the demographic data and outcome

variables between the intervention and control

groups at baseline. Pairwise comparisons with the

P value adjusted using Bonferroni correction was

used to examine for the differences in UI7 between

week 1 and the subsequent time points during the

intervention period (eg between week 1 and 2, week

1 and 3, etc). The results were presented as mean

(standard deviation [SD]).

Results

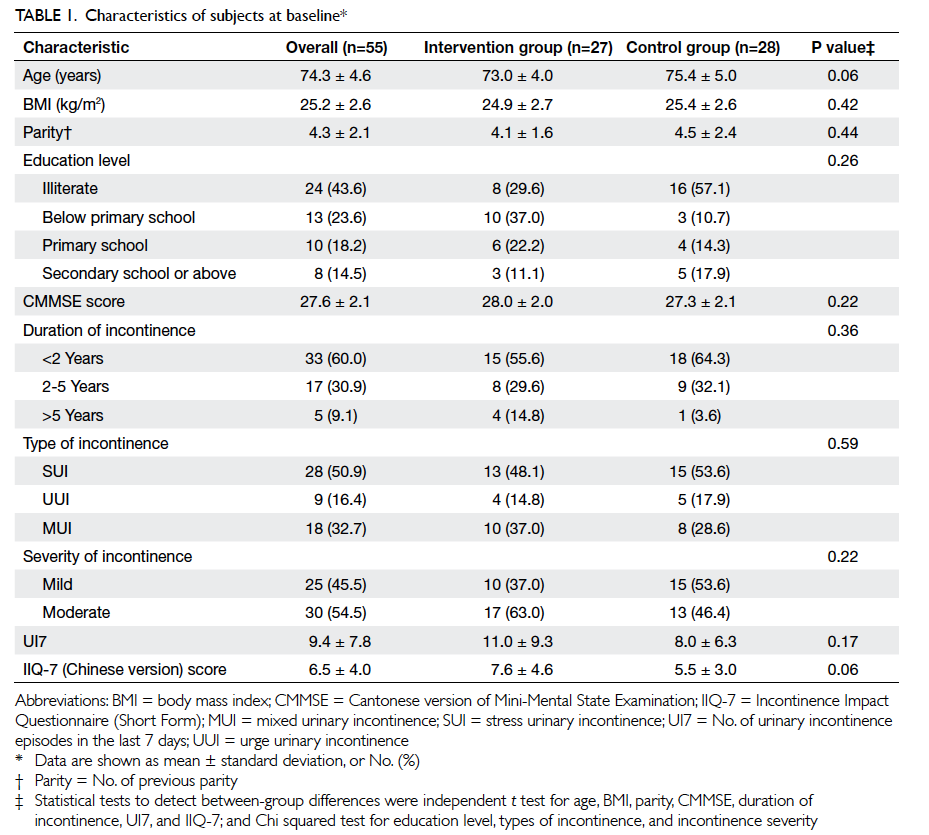

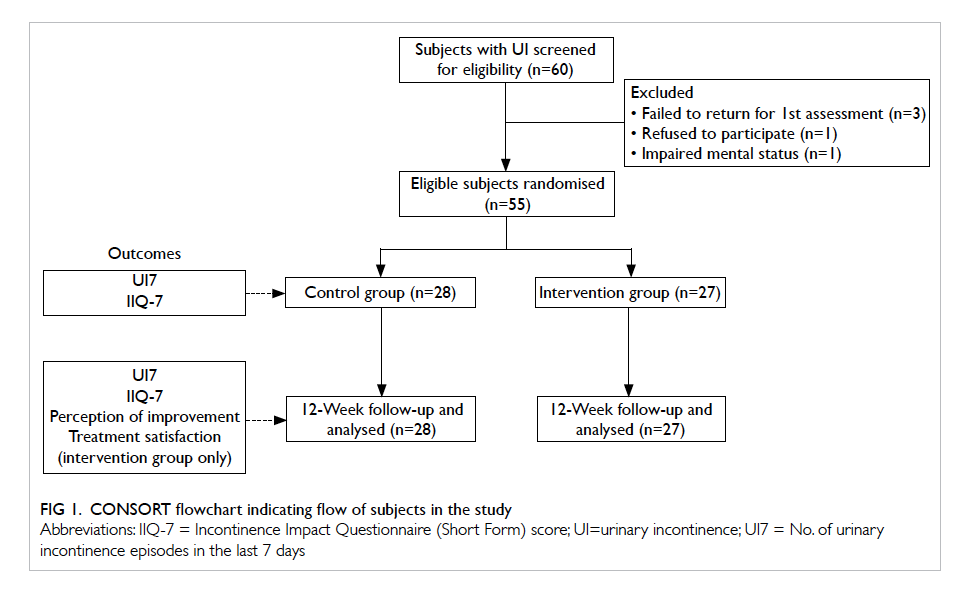

The demographics and baseline measurements for the participants are shown in Table 1. Of the 60

participants recruited for screening, three did not turn up for assessment, one declined to participate

in the study, and one was excluded due to impaired mental status (Fig 1). The majority of the participants were in their 70s with a mean (± SD) age of 74.3

± 4.6 years. There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of age, BMI, parity,

education level, mental status (CMMSE), and the characteristics of UI at baseline.

Number of urinary incontinence episodes in 7 days

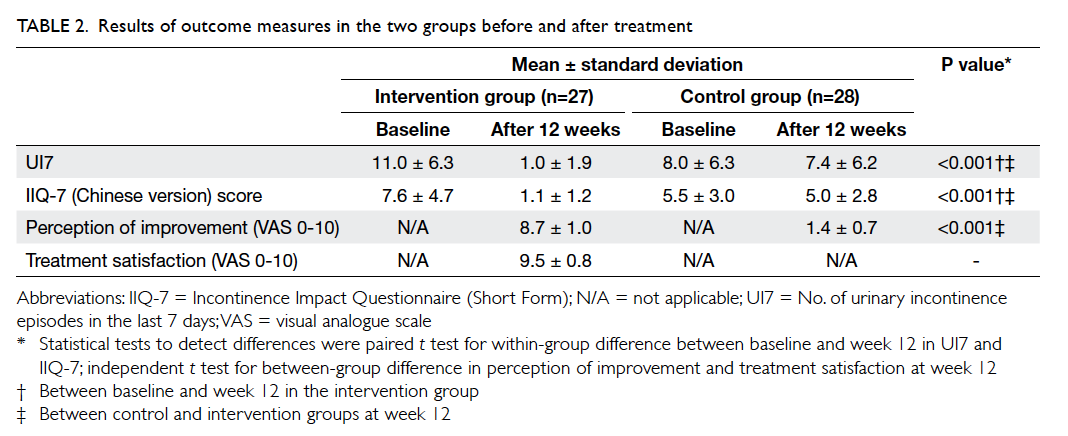

There was a significant interaction between time and groups in UI7 (F(1,53) = 33.14; P<0.001). A significant

reduction in UI7 was noted only in the intervention group. There was significant difference between the

control and intervention groups (t = –5.3; P<0.001) at 12 weeks with a mean difference of -6.4 (95% confidence interval [CI], -8.9 to -3.9). The mean numbers of UI7 for intervention and control groups were 1.0 ± 1.9 (95% CI, 0.3-1.7) and 7.4 ± 6.2

(95% CI, 5.0-9.8), respectively, at 12 weeks (Table 2). When comparing the percentage reduction ([pre-treatment frequency – post-treatment frequency] / [pre-treatment frequency] x 100%) in UI7, the intervention group demonstrated a mean of more than 90% reduction versus 7.2% in the control group.

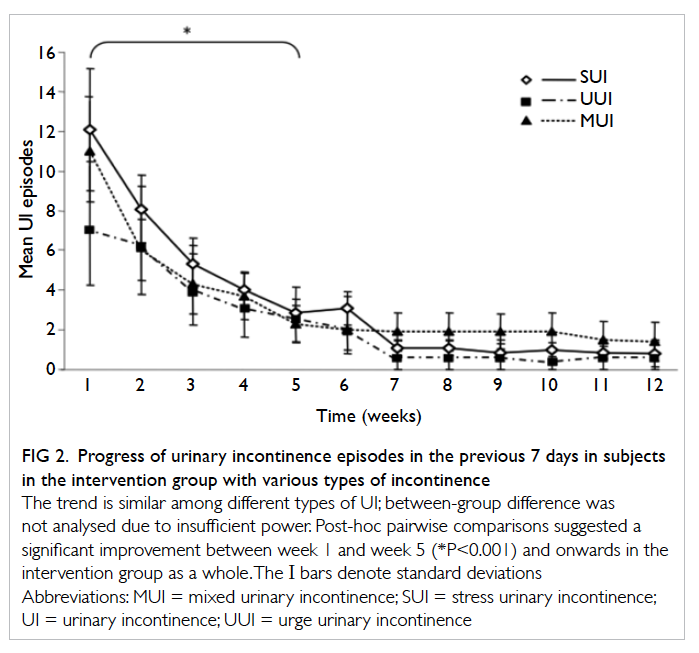

A similar trend of improvement was shown in subjects with SUI, UUI, and MUI; however, statistical analysis was not performed due to insufficient power (Fig 2). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons (a total of 11) suggested a significant improvement from week 1 to week 5 and onwards (P<0.001) in the intervention group.

Figure 2. Progress of urinary incontinence episodes in the previous 7 days in subjects in the intervention group with various types of incontinence

Incontinence Impact Questionnaire Short

Form modified Chinese (Taiwan) version

A significant interaction between time and groups

was noted (F(1,53) = 54.56; P<0.001). As IIQ-7 was

non-normally distributed, Mann-Whitney test was

used and revealed a significant reduction of IIQ-7 (ie

improvement in QoL) only in the intervention group

(P<0.001), with a mean difference of -3.9 (95% CI,

-5.1 to -2.8) at 12 weeks (Table 2).

Perception of improvement, treatment

satisfaction, attendance, exercise compliance,

and attrition rate

The results of the subjective perception of

improvement and level of satisfaction with treatment

after 12 weeks are shown in Table 2. The majority

of the participants in the intervention group were

satisfied with the interventions and perceived a

subjective improvement. The mean attendance and

exercise compliance rates in the intervention group

were 97.7% ± 5.0% and 99.4% ± 1.9%, respectively.

The attrition rate was zero in both groups during the

whole study period. No adverse effect or discomfort

was reported during the intervention period.

Discussion

In line with results from previous studies, this study

further confirms that PFMT is an effective and

safe treatment for women suffering from various

types of UI. However, we observed a mean of >90%

reduction in UI episodes which is noticeably higher

than that reported in previous similar studies (32%

to 73% reduction).18 19 Although recommendation

of PFMT for women with UI is strongly supported by previous research findings,7 the best approach of

PFMT programme continues to remain unclear.11

One possible explanation for the superior outcome

in this study might be the combination of a few

effective features in this programme, including

programme duration of 12 weeks with gradual

exercise progression, combination of PFMT and

BT, manual vaginal palpation, and one-on-one

supervised training session. First, the design of this

UCPP incorporated some important concepts of

exercise therapy. The training period of this study

was 12 weeks, which could optimise the effect of

the neural adaptation (recruitment of efficient

motor units and frequency of excitation) and muscle

hypertrophy according to the recommendations

made by the American College of Sports Medicine.20

In addition, a recent systematic review7 also revealed

that implementation of PFMT programme for at

least 3 months (ie around 12 weeks) is more likely to

result in greater treatment effect versus that lasting

for <12 weeks. This programme also adopted the

concepts raised by Kegel16 in which the progression

of the exercise regimen is designed according

to different stages, namely muscle awareness,

strengthening, endurance, habit building, and

muscle utilisation. Previous studies suggested

a negative correlation between increased PFM

strength and UI symptoms.21 22 The improvement

of UI7 at the end of the UCPP might be a direct

result of the muscle training programme, although

PFM strength was not measured in this study.

Theoretically, skeletal muscle strengthening should

be facilitated by using additional resistance20 and,

therefore, it is questionable whether muscle strength

could be increased by UCPP using only maximal

voluntary contractions. However, a previous study

has indicated muscle strength improvement with

daily practice of voluntary PFM contraction without

resistance,20 and absence of extra improvement in

UI patient groups with intravaginal resistance as

compared with the group without resistance.23

Second, a combination of PFMT and BT

was used in this UCPP. Although PFMT has been

recommended as first-line management, even for

women with UUI and MUI,7 there is some evidence

suggesting superior outcome with combined PFMT

and BT in this population.9 The result of this study

confirmed these suggestions as a similar pattern of

improvement was observed across the three groups

(UUI, SUI, and MUI), although statistical analysis of

the difference between subgroups was not performed

due to the small sample size.

Third, vaginal palpation was used to facilitate

and ensure correct PFM contraction. It was reported

that approximately 30% of women are unable to

perform isolated pelvic floor contractions with only

written or verbal instructions.21 We consider the

extra proprioceptive cue and specific verbal feedback

are an integral part of the PFMT, and consider these

to play a crucial role, especially in the initial (muscle

awareness) stage. Ensuring feedback may also

increase exercise adherence and compliance, apart

from improving the treatment outcomes.

Fourth, the exercise sessions were conducted on

a one-on-one basis for 30 minutes each. It has been

reported that the amount of contact with health care

professionals is positively correlated with reported

cure and improvement (eg perception of change and

incontinence-specific QoL) in patients with UI.11

It is argued that women receiving more attention

may overestimate their improvement to please the

treatment provider (ie experimenter effect),11 and it

is strongly suggested to include more ‘objective’ data

such as leakage episode outcomes in all PFMT trials.

The result of this study revealed improvement in UI7

as well as other subjective measures (IIQ-7, perception

of improvement, and treatment satisfaction), which

could be considered as additional evidence base.11

The subjects’ compliance with the treatment

programme was excellent, as reflected by the high

compliance rate with exercise regimens, high

attendance rate, and zero dropouts; the dropout

rates reported in previous studies were relatively

high, ranging from 12% to 41%.6 18 24 A possible

explanation for such good compliance might be the

significant improvement in the early stage of the

protocol, which in turn increased the participants’

motivation for and confidence in adhering with

the PFMT programme. Regular meetings (weekly

or bi-weekly) with the same physiotherapist, who

offered continuity of care, could be another possible

explanation for the favourable compliance.

Study limitations

The main limitations in this study were: (1) potential

selection bias due to use of convenience sampling,

(2) absence of assessor blinding, (3) possibility of

over-reporting, and (4) the use of the modified IIQ-7

Chinese (Taiwan) version. It has been acknowledged

that convenient sampling might not be

representative of the whole population suffering from

UI. On the other hand, our subject group might have

similar care-seeking behaviour as the client group in

clinical practice. Although statistically insignificant,

the data showed a small difference in some aspects

of the demographic characteristics. In general, the

control group tended to be slightly older (75.4 years

vs 73.0 years), more likely to be illiterate, and have

milder severity, and shorter duration of UI versus

the intervention group. As these slight differences in

the demographics might induce confounding, their

effects warrant further investigation. Nevertheless,

interpretation of the results of this study deserves

some caution. In this study, five participants

recruited for screening did not join the programme

due to various reasons (one denied, three failed

to turn up, and one due to impaired mental status). Although the specific reason for the

absence of three participants was not investigated,

the possibility of self-selection bias should be

considered. In addition, all involved parties (the

assessor, treatment provider, and the participants)

were not blinded to the intervention, as opposed to

the ideal experimental setup. However, it is widely

acknowledged that given the nature of the treatment

programme, it is difficult and often impossible to

blind the treatment provider and participants during

treatment.11 Due to resource limitation, it was not

possible to include an independent, blinded assessor

for outcome assessment. We were well aware of the

possible ‘experimenter effect’, and therefore used

UI7 as our primary outcome measure which is

considered a more objective measure to minimise

the possible effect of over-reporting of subjective

improvement,11 although its ‘objectivity’ remains

controversial. In addition, a significant proportion of

participants (approximately 44%) required assistance

for completing the outcome questionnaires due to

illiteracy. This could possibly lead to over-reporting

of improvement. Furthermore, the possibility of

over-reporting of compliance by participants using

self-reported weekly exercise diary should not be

overlooked. There is, however, no better measure

available to monitor the performance of this type of

exercise accurately. A recent randomised controlled

trial25 reported that severity of SUI symptoms at

baseline and extent of PFM strength improvement,

rather than exercise adherence, were correlated

with symptom reduction for women with SUI.

The result suggested a complex interaction between

subject’s health condition, exercise compliance

and treatment effectiveness, which warrant further

investigation. Therefore, we intended not to account

the improvement observed in our intervention group

to the high self-reported compliance rate. Finally,

a modified Chinese (Taiwan) version of IIQ-7 was

used in this study. We are aware of the fact that this

version has not been properly validated. However,

we do not believe this affects our results as the

modification was minor and the version was highly

comparable with the Hong Kong version which was

validated subsequent to the current study.

This study examined the immediate

effectiveness of the verbally instructed UCPP just

after cessation of supervised training. No follow-up

data were collected. It is recommended that the long-term

effectiveness of UCPP be explored, especially in

the light of fairly extensive literature which reported

poor long-term adherence and relapse at 3 to 5 years

following pelvic floor rehabilitation programme.26

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that a structured 12-week

programme of PFMT with gradual exercise

progression, BT with urgency suppression, and

enhanced education is likely to improve episodes of

urinary leakage and QoL in older Chinese women

with various kinds of UI in a community setting.

References

1. Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of

terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from

the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International

Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn 2002;21:167-78. CrossRef

2. Klausner AP, Vapnek JM. Urinary incontinence in the

geriatric population. Mt Sinai J Med 2003;70:54-61.

3. Pang MW, Leung HY, Chan LW, Yip SK. The impact of

urinary incontinence on quality of life among women in

Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2005;11:158-63.

4. Cheung RY, Chan S, Yiu AK, Lee LL, Chung TK. Quality

of life in women with urinary incontinence is impaired and

comparable to women with chronic diseases. Hong Kong

Med J 2012;18:214-20.

5. Aguilar-Navarro S, Navarrete-Reyes AP, Grados-Chavarria

BH, Garcia-Lara JM, Amieva H, Avila-Funes JA. The

severity of urinary incontinence decreases health-related

quality of life among community-dwelling elderly. J

Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2012;67:1266-71. CrossRef

6. Fan HL, Chan SS, Law TS, Cheung RY, Chung TK. Pelvic

floor muscle training improves quality of life of women

with urinary incontinence: a prospective study. Aust N Z J

Obstet Gynaecol 2013;53:298-304. CrossRef

7. Dumoulin C, Hay-Smith J. Pelvic floor muscle training

versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for

urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev 2010;(1):CD005654.

8. Pereira VS, de Melo MV, Correia GN, Driusso P. Long-term

effects of pelvic floor muscle training with vaginal cone

in post-menopausal women with urinary incontinence:

a randomized controlled trial. Neurourol Urodyn

2013;32:48-52. CrossRef

9. Wallace SA, Roe B, Williams K, Palmer M. Bladder training

for urinary incontinence in adults. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev 2004;(1):CD001308.

10. Kim H, Yoshida H, Suzuki T. The effects of multidimensional

exercise treatment on community-dwelling elderly

Japanese women with stress, urge, and mixed urinary

incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs

Stud 2011;48:1165-72. CrossRef

11. Hay-Smith EJ, Herderschee R, Dumoulin C, Herbison GP.

Comparisons of approaches to pelvic floor muscle training

for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database

Syst Rev 2011;(12):CD009508.

12. Lagro-Janssen TL, Debruyne FM, Smits AJ, van Weel C.

Controlled trial of pelvic floor exercises in the treatment

of urinary stress incontinence in general practice. Br J Gen

Pract 1991;41:445-9.

13. Chiu HF, Lee HC, Chung WS, Kwong PK. Reliability and

validity of the Cantonese version of Mini-Mental State

Examination: a preliminary study. J Hong Kong Coll Psych

1994;4:25-8.

14. World Medical Association. World Medical Association

Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical

research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013;310:2191-4. CrossRef

15. Miller JM, Sampselle C, Ashton-Miller J, Hong GR,

DeLancey JO. Clarification and confirmation of the Knack

maneuver: the effect of volitional pelvic floor muscle

contraction to preempt expected stress incontinence. Int

Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2008;19:773-82. CrossRef

16. Kegel AH. Physiologic therapy for urinary stress

incontinence. J Am Med Assoc 1951;146:915-7. CrossRef

17. Tsai CH. The effectiveness of a pelvic floor muscle

rehabilitation program in managing urinary tract

incontinence among Taiwanese middle age and older

women [dissertation]. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh;

2001.

18. Castro RA, Arruda RM, Zanetti MR, Santos PD, Sartori

MG, Girao MJ. Single-blind, randomized, controlled trial of

pelvic floor muscle training, electrical stimulation, vaginal

cones, and no active treatment in the management of stress

urinary incontinence. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2008;63:465-72. CrossRef

19. Zahariou A, Karamouti M, Georgantzis D, Papaioannou P.

Are there any UPP changes in women with stress urinary

incontinence after pelvic floor muscle exercises? Urol Int

2008;80:270-4. CrossRef

20. Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, et al. American

College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity

and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining

cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness

in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing

exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43:1334-59. CrossRef

21. Bø K. Pelvic floor muscle strength and response to pelvic

floor muscle training for stress urinary incontinence.

Neurourol Urodyn 2003;22:654-8. CrossRef

22. Dannecker C, Wolf V, Raab R, Hepp H, Anthuber C. EMG-biofeedback

assisted pelvic floor muscle training is an

effective therapy of stress urinary or mixed incontinence: a

7-year experience with 390 patients. Arch Gynecol Obstet

2005;273:93-7. CrossRef

23. Herbison GP, Dean N. Weighted vaginal cones for

urinary incontinence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2013;(7):CD002114.

24. Hay-Smith EJ, Bø Berghmans LC, Hendriks HJ, de Bie RA,

van Waalwijk van Doorn ES. Pelvic floor muscle training

for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database

Syst Rev 2001;(1):CD001407.

25. Hung HC, Chih SY, Lin HH, Tsauo JY. Exercise adherence

to pelvic floor muscle strengthening is not a significant

predictor of symptom reduction for women with urinary

incontinence. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93:1795-800. CrossRef

26. Bø K, Hilde G. Does it work in the long term?—A systematic

review on pelvic floor muscle training for female stress

urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 2013;32:215-23. CrossRef

Find HKMJ in MEDLINE: