Hong Kong Med J 2014 Dec;20(6):495–503 | Epub 12 Sep 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144245

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dermoscopy for common skin problems in Chinese children using a novel Hong Kong–made dermoscope

David CK Luk, MSc, FHKAM (Paediatrics); Sam YY Lam, MB, ChB, MRCPCH; Patrick CH Cheung, FRCPCH, FHKAM (Paediatrics); Bill HB Chan, FRCPCH, FHKAM (Paediatrics)

Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr David CK Luk (davidluk98@hotmail.com)

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the dermoscopic features of

common skin problems in Chinese children.

Design: A case series with retrospective qualitative

analysis of dermoscopic features of common skin

problems in Chinese children.

Setting: A regional hospital in Hong Kong.

Participants: Dermoscopic image database, from

1 May 2013 to 31 October 2013, of 185 Chinese

children (aged 0 to 18 years).

Results: Dermoscopic features of common

paediatric skin problems in Chinese children were

identified. These features corresponded with the

known dermoscopic features reported in the western

medical literature. New dermoscopic features were

identified in café-au-lait macules.

Conclusion: Dermoscopic features of common

skin problems in Chinese children were consistent

with those reported in western medical literature.

Dermoscopy has a role in managing children with

skin problems.

New knowledge added by this

study

- This is the first research on dermoscopy in Chinese children.

- Dermoscopic features reported in western medical literature could be identified in Chinese children.

- Routine use of dermoscopy has a role in managing paediatric skin problems.

Introduction

Skin complaints are common in both community-based

and hospital paediatric practices. The range

of skin problems is diverse, including categories

like inflammatory conditions (eg eczema, psoriasis),

birthmarks (eg haemangiomas, port-wine stains,

melanocytic naevi), infectious skin diseases, and hair

and nail problems.

In many situations, the clinical diagnosis

of paediatric skin problems is straightforward

but masquerading conditions also exist.1 2 Although histopathological examination can confirm the

clinical diagnosis, skin biopsy in young children

may require special arrangements such as sedation.

In recent years, the gap between clinical and

histopathological examination of skin lesions has

been filled by various skin imaging modalities.3 4 As a simple, quick,5 non-invasive clinical technique,

dermoscopy has gained popularity in the examination

of skin in western countries.6 7 Dermoscopy refers to the examination of skin with a handheld device to reveal surface and subsurface skin structures. This is

achieved by an optical system to magnify, illuminate,

and remove light flare and reflection from the skin

surface. It provides the link between eyeball clinical

inspection and histopathological examination. With more than 1500 articles published after its

introduction in 1980s, dermoscopy has been

established as a routine skin examination technique

in many western countries.8 As dermoscopy is

extremely useful in the diagnosis of malignant

melanoma9 and is able to reduce the need for skin

biopsy,10 11 it is most widely used in the management

of pigmented skin lesions. Recently, dermoscopic

features of a wide range of non-pigmented skin

problems have also been reported.12 13 With the

uncovering of more dermoscopic features,

dermoscopy has gained importance in the diagnosis of skin lesions, and its benefits in educating medical

students and use in family practice have also been

published recently.14 15 16

Medical researches on dermoscopy in Chinese populations, however, have rarely been published.17 18 19

With the understanding that ethnicity may affect

dermoscopic findings,20 the aim of this study was to

identify dermoscopic features in Chinese children

and assess if those are in line with internationally

published features.

The clinical use and research on dermoscopy

in children worldwide had been limited by both patient

factors and equipment factors. Camera-mounted

dermoscope required lengthy setup and was not user-friendly

in busy clinics. In addition, babies and young

children might not stay still during the examination.

To ensure an efficient dermoscopic examination and

a good-quality dermoscopy image capture, a novel

device developed by the biomedical engineering team

of the Hong Kong Productivity Council was applied.

This study evaluated the dermoscopic features of

common skin problems in Chinese children using

the dermoscopy image database established with the

dermoscope.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of the dermoscopic features

of skin lesions of Chinese children (aged 0-18 years)

was performed. The study was approved by the

local Research Ethics Committee and conducted

at the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent

Medicine, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong,

using the dermoscopic image database from 1 May

2013 to 31 October 2013, which contained only

cases with symptoms and signs classical for their

respective clinical diagnoses. These images were

examined by a paediatrician trained in dermoscopy.

A two-step algorithm was used to assess dermoscopy

images with the first step aiming at differentiating

melanocytic from non-melanocytic lesions and the

second step on specific pattern analysis. The results

of the analysis were categorised according to the

clinical diagnoses.

Literature search of the MEDLINE database

was performed to identify specific dermoscopic

features for each clinical diagnosis. The key words

used in the literature search were “dermoscopy,

dermatoscopy, dermoscope, dermatoscope”.

Key words specific to individual clinical diagnosis

were used to facilitate the search. It was then

assessed if the dermoscopic features of this study

corresponded with those from published medical

literature.

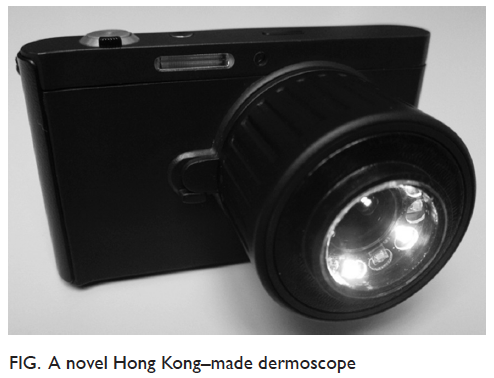

During the study period, all dermoscopy

images were captured by the novel Hong Kong–made dermoscope. It was an all-in-one pocket-size

autofocusing polarised digital dermoscope with

Wi-Fi and USB connectivity capable of capturing

dermoscopy image of all ages including young infants within 5 seconds

(Fig). An extensible optic barrel was hinged on the body

of the dermoscope so that both gross photos and 10-times magnified dermoscopy photos could be taken.

The images were then uploaded to a computerised

dermoscopy image database.

Results

Dermoscopic images of 185 Chinese children (86

boys and 99 girls) suffering from 22 skin conditions

were retrieved. The mean age of these children was

5.2 years (range, 2 days to 17 years). The top 12 diagnoses reported (in descending order of frequency)

were port-wine stain (n=42), melanocytic naevus

(n=41), haemangioma (n=30), café-au-lait macule

(CALM; n=15), sebaceous naevus (n=8), viral wart

(n=7), atopic dermatitis (n=6), alopecia areata (n=5),

cutis aplasia (n=5), psoriasis (n=4), scabies (n=3),

and molluscum contagiosum (n=3).

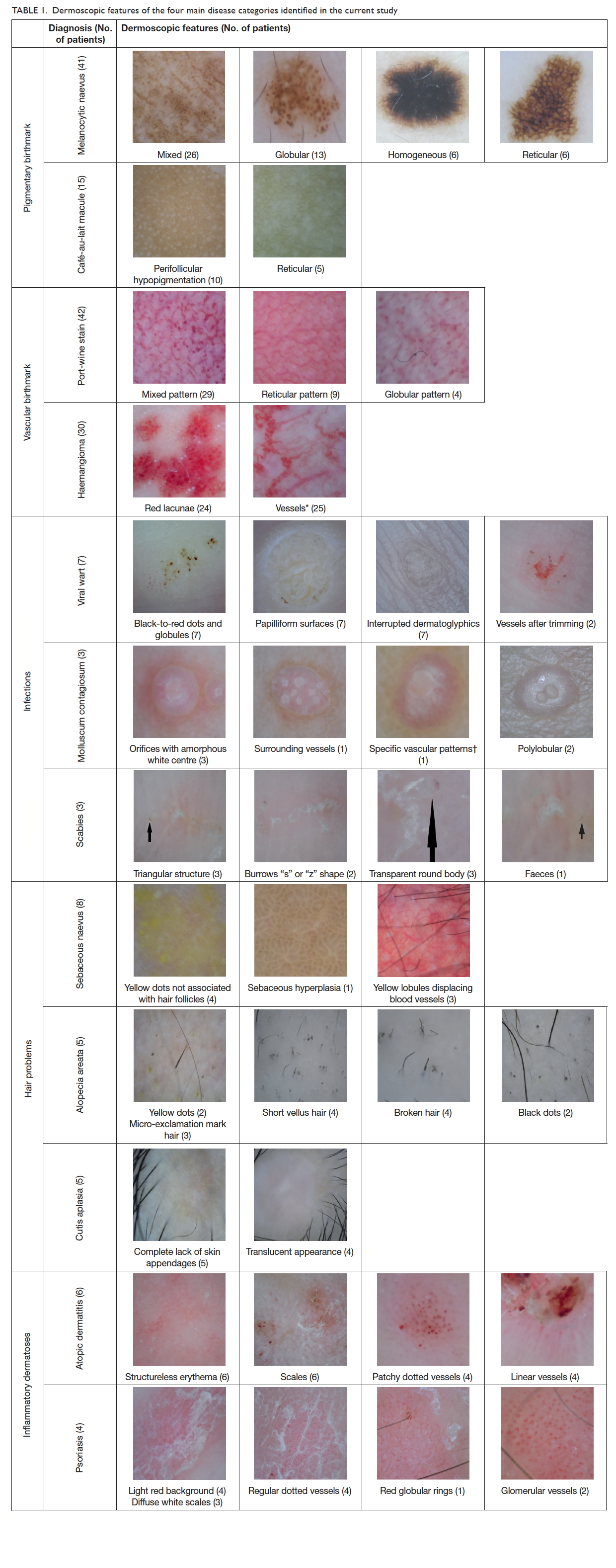

The dermoscopic features of these 12 diagnoses

were further analysed. They were grouped into four

main disease categories: birthmarks (pigmentary

and vascular), infections, hair problems, and

inflammatory dermatoses. Forty-two dermoscopic

features were identified (Table 1).

In the pigmentary birthmark category, there were

41 children with 51 melanocytic naevi (mean age, 7.3

years). The most common dermoscopic pattern of

melanocytic naevus was mixed, followed by globular,

homogeneous, and reticular. In the mixed pattern

naevi, globular-homogeneous was the commonest

(n=13), followed by globular-reticular-homogeneous

(n=6), reticular-homogeneous (n=4), and globular-reticular

(n=3). There were 15 children with CALM

(mean age, 3.5 years). All 10 children with facial

CALM showed a homogeneous brown patch with

perifollicular hypopigmentation. The five children

with CALM on neck showed a reticular pattern.

In the vascular birthmark category, there were

42 children with port-wine stains (mean age, 6.5

years) and 30 infants with infantile haemangiomas (mean

age, 6 months). For those with port-wine stains,

both globular (n=4) and reticular (n=9) vascular

patterns were identified but the most common

dermoscopic pattern was mixed pattern (n=29) with

both globular and reticular components. Among the

30 infantile haemangiomas, 25 had vessels of various

morphologies, and red lacunae were noted in 24.

None of the haemangiomas had melanocytic pattern.

In the infectious diseases category, there were

seven children with viral warts on hands or feet (mean

age, 10.5 years). Thrombosed capillaries presented

as black-to-red dots, and papilliform surfaces and

interrupted skin lines were identified in all cases. All

three children with molluscum contagiosum (mean

age, 5 years) showed orifices but vessels and specific

vascular patterns could be found in only one case.

In the three cases of scabies (mean age, 12.5 years),

triangular head, transparent body, and burrows were

present.

Patients with patchy alopecia were identified in

the hair category. Eight patients had sebaceous naevus

(mean age, 8.4 years), with four having yellow dots

not associated with hair follicles, three having yellow

lobules displacing blood vessels, and one having

sebaceous hyperplasia. In the five patients with

alopecia areata (mean age, 12 years), dermoscopic

features including yellow dots (n=2), black dots

(n=2), short vellus hair (n=4), broken hair (n=4), and

micro-exclamation mark hair (n=3) were noted. Five

patients with cutis aplasia (mean age, 3 years) were

featured by a complete lack of skin appendages (n=5)

and translucent appearance (n=4).

There were six patients with atopic dermatitis

(mean age, 6.5 years) and four patients with psoriasis

(mean age, 11 years) in the inflammatory dermatoses

category. Atopic eczema was featured by structureless

erythema (n=6), scales (n=6), and patchy dotted

vessels (n=4) while the psoriasis patients had light

red background (n=4), diffuse white scales (n=3),

regular dotted vessels (n=4), and glomerular vessels

(n=2).

Discussion

Our study documented the dermoscopic findings

of common paediatric skin conditions in Chinese

children. In the analysis of the dermoscopy images using

a two-step algorithm, the first step was differentiation

between melanocytic and non-melanocytic lesions.

This study identified typical melanocytic patterns

(globular and reticular pattern21) in melanocytic

naevi, and absence of melanocytic patterns in all

haemangiomas. This two-step algorithm analysis

of skin lesions confirmed the findings on clinical

inspection and provided a standard approach to

dermoscopic examination even in difficult cases.

Birthmarks are very common in children.

Salmon patches occur in half of the neonates22 23 and infantile haemangiomas in one tenth of premature babies,

while the prevalence of capillary malformations

(port-wine stain) has been reported to be 0.3% to

2.1%.24 25 Within the vascular birthmark category,

both port-wine stains and haemangiomas could

present as neonatal erythematous patches. As

lacunae pattern was commonly identified in

haemangiomas but not in port-wine stains, it may

serve to differentiate haemangiomas from port-wine

stains. An early diagnosis of haemangiomas facilitates

timely management as some may rapidly proliferate

or develop complications in the first few months of

life. In our series, the majority of the port-wine stain

lesions showed a mixed pattern with both globular

and reticular components (n=29/42) while reticular

(n=9/42) and globular (n=4/42) patterns were less

common. The ectatic capillary plexus was situated

deeper in the dermis in those with a reticular pattern

than those with a globular pattern; this difference

may have treatment and prognostic implications on response to laser treatment.13 As such,

laser treatment strategy aiming at the deeper dermal

layer would be required to improve treatment

results.

In the pigmentary birthmark category, both

congenital and acquired melanocytic naevi were

included. The common dermoscopic patterns

of globular, reticular, homogeneous, and mixed

reported in our series were in line with those

reported in the western medical literature.26 27 28 29 As

dermoscopy improves the detection of melanomas,30

its use was suggested in the monitoring of congenital

melanocytic naevi (CMN), especially the smaller

CMN.31 32 33 Sequential digital dermoscopy imaging

can also reduce the unnecessary excision of

suspicious pigmented skin lesions.34 This has been

emphasised in children with epidermolysis bullosa

who are at risk of developing skin cancers, and in

whom overtreatment of the fragile skin should be avoided.35

This is the first report of dermoscopic features

of CALM in medical literature. It was noted that the

dermoscopic patterns of CALM might vary according

to the location on the body. All the 10 cases of facial

CALM showed homogeneous brown patches with

perifollicular hypopigmentation while the five cases

of CALM on the neck had a faint brown reticular

pattern. As it may be difficult to differentiate CALM

from CMN in infancy by inspection,36 dermoscopy

provides a quick and non-invasive diagnostic tool to

guide subsequent management.

In the infectious disease category, all viral

warts were on the hands or feet, and all of them

showed the classical features of thrombosed

capillaries present as black-to-red dots and

globules on papilliform surfaces with interrupted

skin lines. These findings were consistent with

features reported in the medical literature.37 The

confirmation of the diagnosis of viral wart before

initiating treatment is important because acral

melanoma, which is more common in Chinese, has

been reported to be misdiagnosed as viral wart with

disastrous consequences.38 39 40 Moreover, dermoscopy

could help guide treatment by identifying residual

warty structures or confirming complete resolution

of warts.37

In our series, there were three children with

scabies who had either the classical dermoscopic

sign of ‘triangular structure’41 or the round bodies42 43

of the scabies mite. The “z”- or “s”-shaped burrows

were also well depicted on dermoscopy in two

of them. Dermoscopy is a simple, accurate, and

rapid44 technique for diagnosing scabies even in

inexperienced hands.45 In a study involving 756

patients, dermoscopic examination for scabies was

found to be 91% sensitive and 86% specific.45 It

greatly enhances treatment decisions45 and allows

fast introduction of proper treatment.42 Diagnosing

scabies in children by dermoscopy is child-friendly

as it requires no skin scrappings, thus, causing no

fear or pain.42 In addition, demonstration of scabies

mite to patient may foster treatment adherence in

both patients and asymptomatic family members.44

Molluscum contagiosum is a common skin

infection in children46 and is highly contagious47

with outbreaks reported.48 In our three children with

molluscum contagiosum, the reported dermoscopic

features included orifices with amorphous white

centre and polylobular appearance surrounded

by vessels.49 50 When the typical clinical features

of molluscum contagiosum are not apparent,

dermoscopy can be helpful for diagnosis.51

Three common causes of patchy alopecia in

children were reported in this study. For neonates

or infants with congenital patchy alopecia, the

differentiation between sebaceous naevus and

cutis aplasia may be difficult.52 In our study, the

dermoscopic features of sebaceous naevi with yellow

dots unassociated with hair follicles, sebaceous

hyperplasia, and yellow lobules displacing blood

vessels53 were demonstrated. On the other hand, cutis

aplasia showed a complete lack of skin appendages

and skin translucency.52 While no specific treatment

is usually needed for cutis aplasia, surgical excision

of sebaceous naevi is often advised with its potential

for developing into basal cell carcinoma.54

The lifetime risk of alopecia areata in the

general population is approximately 1.7% and as

many as 60% of patients with alopecia areata have

disease onset before 20 years of age.55 The clinical

features of hair loss vary with clinical subtypes.56 In

our series of five children with alopecia areata, black

dots, yellow dots, short vellus hair, broken hair, and

micro-exclamation mark hairs were noted. These

dermoscopic features may be useful clinical indicators

in alopecia areata which have both diagnostic and

prognostic values.57 58

Concerning the inflammatory dermatoses category, clinical similarities exist between atopic

dermatitis and psoriasis as both are chronic pruritic

scaly erythematous skin conditions. It is known

that characteristic dermoscopic vascular patterns

facilitate differentiation of psoriasis from atopic

dermatitis.59 In our study, the patchy dotted vessels60

and linear vessels of atopic dermatitis could be

differentiated from the red globular rings61 and

glomerular vessels62 of psoriasis.

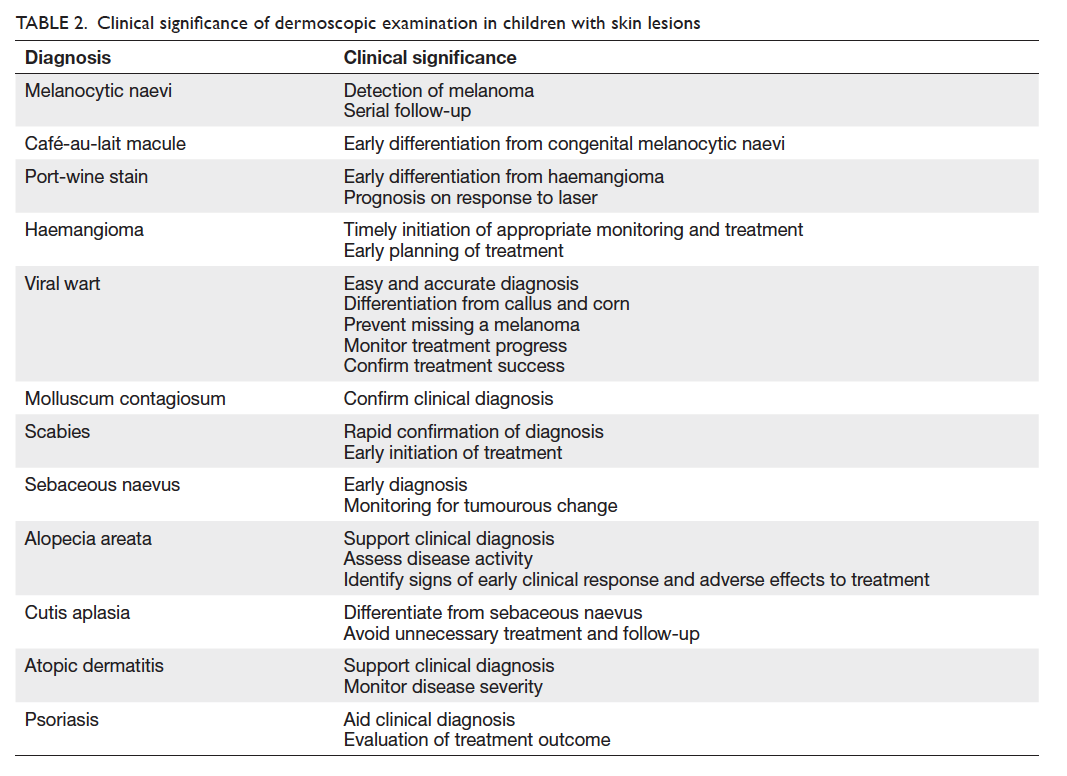

The clinical significance of dermoscopy in

children’s skin conditions is summarised in Table 2.

Although various dermoscopic features of

skin problems could be identified in this study,

it had several limitations. First, the dermoscopy

database only contained images captured during

routine clinical service when the clinical features were classical of their respective diagnosis. As such, the database was

not representative of all common skin problems in

children. In addition, with the small case numbers

for some of the diseases such as atopic dermatitis

and psoriasis, further research is required to confirm

our preliminary findings. Moreover, features of skin

diseases in children are age-dependent and phase-dependent

but these factors were not evaluated in

the present study.

Conclusion

Dermoscopy is a well-established skin examination

tool with known dermoscopic features for many diagnoses.

Our study confirmed that the dermoscopic features

reported in the medical literature could be identified

in Chinese children. While the value of dermoscopy

in diagnostic, prognostic, and disease monitoring

is being unveiled, further studies are required to

understand its role in various

paediatric skin diseases.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms Carol YB Liu and Mr Bryan MK So of Hong Kong

Productivity Council and Hong Kong Innovation

and Technology Fund for the support on the dermoscopy device for this study.

Declaration

David CK Luk acted as advisor to Hong Kong

Productivity Council on the development of

dermoscope prototype. No conflicts of interests

were declared by authors.

References

1. Ng BC, San CY, Lau EY, Yu SC, Burd A. Multidisciplinary

vascular malformations clinic in Hong Kong. Hong Kong

Med J 2013;19:116-23.

2. Hon KL, Leung TF, Cheung HM, Chan PK. Neonatal

herpes: what lessons to learn. Hong Kong Med J 2012;18:60-2.

3. Koehler MJ, Lange-Asschenfeldt S, Kaatz M. Non-invasive

imaging techniques in the diagnosis of skin diseases.

Expert Opin Med Diagn 2011;5:425-40. CrossRef

4. Sharif SA, Taydas E, Mazhar A, et al. Noninvasive clinical

assessment of port-wine stain birthmarks using current

and future optical imaging technology: a review. Br J

Dermatol 2012;167:1215-23. CrossRef

5. Jaimes N, Dusza SW, Quigley EA, et al. Influence of time

on dermoscopic diagnosis and management. Australas J

Dermatol 2013;54:96-104. CrossRef

6. Venugopal SS, Soyer HP, Menzies SW. Results of

a nationwide dermoscopy survey investigating the

prevalence, advantages and disadvantages of dermoscopy

use among Australian dermatologists. Australas J Dermatol

2011;52:14-8. CrossRef

7. Engasser HC, Warshaw EM. Dermatoscopy use by US

dermatologists: a cross-sectional survey. J Am Acad

Dermatol 2010;63:412-9, 419.e1-2.

8. Tasli L, Kaçar N, Argenziano G. A scientometric analysis

of dermoscopy literature over the past 25 years. J Eur Acad

Dermatol Venereol 2012;26:1142-8. CrossRef

9. Inoue Y, Menzies SW, Fukushima S, et al. Dots/globules on

dermoscopy in nail-apparatus melanoma. Int J Dermatol

2014;53:88-92. CrossRef

10. Argenziano G, Catricalà C, Ardigo M, et al. Dermoscopy

of patients with multiple nevi: improved management

recommendations using a comparative diagnostic

approach. Arch Dermatol 2011;147:46-9. CrossRef

11. van der Rhee JI, Bergman W, Kukutsch NA. The impact

of dermoscopy on the management of pigmented lesions

in everyday clinical practice of general dermatologists: a

prospective study. Br J Dermatol 2010;162:563-7. CrossRef

12. Haliasos EC, Kerner M, Jaimes-Lopez N, et al. Dermoscopy

for the pediatric dermatologist part I: dermoscopy of

pediatric infectious and inflammatory skin lesions and hair

disorders. Pediatr Dermatol 2013;30:163-71. CrossRef

13. Haliasos EC, Kerner M, Jaimes N, et al. Dermoscopy for

the pediatric dermatologist, part ii: dermoscopy of genetic

syndromes with cutaneous manifestations and pediatric

vascular lesions. Pediatr Dermatol 2013;30:172-81. CrossRef

14. Liebman TN, Goulart JM, Soriano R, et al. Effect of

dermoscopy education on the ability of medical students

to detect skin cancer. Arch Dermatol 2012;148:1016-22. CrossRef

15. Herschorn A. Dermoscopy for melanoma detection in

family practice [in English, French]. Can Fam Physician

2012;58:740-5, e372-8.

16. Chen LL, Liebman TN, Soriano RP, Dusza SW, Halpern

AC, Marghoob AA. One-year follow-up of dermoscopy

education on the ability of medical students to detect skin

cancer. Dermatology 2013;226:267-73. CrossRef

17. Ye Y, Zhao Y, Gong Y, et al. Non-scarring patchy alopecia

in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus differs from

that of alopecia areata. Lupus 2013;22:1439-45. CrossRef

18. Tan C, Min ZS, Xue Y, Zhu WY. Spectrum of dermoscopic

patterns in lichen planus: a case series from China. J Cutan

Med Surg 2014;18:28-32.

19. Chan G, Ho H. A study of dermoscopic features of

pigmented basal cell carcinoma in Hong Kong Chinese.

Hong Kong J Dermatol Venereol 2008;16:189-96.

20. de Moura LH, Duque-Estrada B, Abraham LS, Barcaui CB,

Sodre CT. Dermoscopy findings of alopecia areata in an

African-American patient. J Dermatol Case Rep 2008;2:52-4. CrossRef

21. Fortina AB, Zattra E, Bernardini B, Alaibac M, Peserico

A. Dermoscopic changes in melanocytic naevi in children

during digital follow-up. Acta Derm Venereol 2012;92:427-9. CrossRef

22. Boon LM, Enjolras O, Mulliken JB. Vascular malformations.

In: Irvine AD, Hoeger PH, Yan AC, editors. Harper’s

textbook of pediatric dermatology. 3rd ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011: 112.1-112.24. CrossRef

23. Leung AK, Barankin B, Hon KL. Persistent salmon patch

on the forehead and glabellum in a Chinese adult. Case Rep

Med 2014;2014:139174.

24. Jacobs AH, Walton RG. The incidence of birthmarks in the

neonate. Pediatrics 1976;58:218-22.

25. Hidano A, Purwoko R, Jitsukawa K. Statistical survey of

skin changes in Japanese neonates. Pediatr Dermatol

1986;3:140-4. CrossRef

26. Aguilera P, Puig S, Guilabert A, et al. Prevalence study

of nevi in children from Barcelona. Dermoscopy,

constitutional and environmental factors. Dermatology

2009;218:203-14. CrossRef

27. Belloni Fortina A, Zattra E, Romano I, Bernardini B,

Alaibac M. Clinical and dermoscopic features of nevi in

preschool children in Padua. Dermatology 2010;220:53;

author reply 54. CrossRef

28. Scope A, Dusza SW, Marghoob AA, et al. Clinical and

dermoscopic stability and volatility of melanocytic nevi

in a population-based cohort of children in Framingham

school system. J Invest Dermatol 2011;131:1615-21. CrossRef

29. Zalaudek I, Schmid K, Marghoob AA, et al. Frequency of

dermoscopic nevus subtypes by age and body site: a cross-sectional

study. Arch Dermatol 2011;147:663-70. CrossRef

30. Haliasos HC, Zalaudek I, Malvehy J, et al. Dermoscopy

of benign and malignant neoplasms in the pediatric

population. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2010;29:218-31. CrossRef

31. Nehal KS, Oliveria SA, Marghoob AA, et al. Use of and

beliefs about dermoscopy in the management of patients

with pigmented lesions: a survey of dermatology residency

programmes in the United States. Melanoma Res

2002;12:601-5. CrossRef

32. Marghoob AA. Congenital melanocytic nevi. In: Marghoob

AA, Malvehy J, Braun RP, editors. Atlas of dermoscopy. London: Informa Healthcare; 2012: 147-58.

33. Rocha CR, Grazziotin TC, Rey MC, Luzzatto L, Bonamigo

RR. Congenital agminated melanocytic nevus—case

report. An Bras Dermatol 2013;88(6 Suppl 1):170-2. CrossRef

34. Gulia A, Massone C. Advances in dermoscopy for detecting

melanocytic lesions. F1000 Med Rep 2012;4:11.

35. de Queiroz Fuscaldi LA, Buçard AM, Alvarez CD, Barcaui

CB. Epidermolysis bullosa nevi: report of a case and review

of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol 2011;3:235-9. CrossRef

36. Bishop JA. Melanocytic naevi and melanoma. In: Irvine

AD, Hoeger PH, Yan AC, editors. Harper’s textbook of

pediatric dermatology. 3rd ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell;

2011: 109.1-109.28. CrossRef

37. Bae JM, Kang H, Kim HO, Park YM. Differential diagnosis

of plantar wart from corn, callus and healed wart with the

aid of dermoscopy. Br J Dermatol 2009;160:220-2. CrossRef

38. Dalmau J, Abellaneda C, Puig S, Zaballos P, Malvehy J. Acral

melanoma simulating warts: dermoscopic clues to prevent

missing a melanoma. Dermatol Surg 2006;32:1072-8. CrossRef

39. Rosen T. Acral lentiginous melanoma misdiagnosed

as verruca plantaris: a case report. Dermatol Online J

2006;12:3.

40. Burd A, Bhat S. An update on the management of

cutaneous melanoma. Hong Kong J Dermatol Venereol

2008;16:143-8.

41. Prins C, Stucki L, French L, Saurat JH, Braun RP.

Dermoscopy for the in vivo detection of sarcoptes scabiei.

Dermatology 2004;208:241-3. CrossRef

42. Kamińska-Winciorek G. Entomodermoscopy in scabies—is it a safe and friendly screening test for scabies in children?

Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2012;20:117-9.

43. Executive Committee of Guideline for the Diagnosis, Ishii

N. Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of scabies in

Japan (second edition). J Dermatol 2008;35:378-93.

44. Fox G. Diagnosis of scabies by dermoscopy. BMJ Case Rep

2009;2009.

45. Dupuy A, Dehen L, Bourrat E, et al. Accuracy of standard

dermoscopy for diagnosing scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol

2007;56:53-62. CrossRef

46. Netchiporouk E, Cohen BA. Recognizing and managing

eczematous id reactions to molluscum contagiosum virus

in children. Pediatrics 2012;129:e1072-5. CrossRef

47. Marsal JR, Cruz I, Teixido C, et al. Efficacy and tolerance

of the topical application of potassium hydroxide (10%

and 15%) in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum:

randomized clinical trial: research protocol. BMC Infect

Dis 2011;11:278. CrossRef

48. Oren B, Wende SO. An outbreak of molluscum

contagiosum in a kibbutz. Infection 1991;19:159-61. CrossRef

49. Zaballos P, Ara M, Puig S, Malvehy J. Dermoscopy of

molluscum contagiosum: a useful tool for clinical diagnosis

in adulthood. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006;20:482-3. CrossRef

50. Morales A, Puig S, Malvehy J, Zaballos P. Dermoscopy of

molluscum contagiosum. Arch Dermatol 2005;141:1644. CrossRef

51. Mun JH, Ko HC, Kim BS, Kim MB. Dermoscopy of giant

molluscum contagiosum. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;69:

e287-8. CrossRef

52. Neri I, Savoia F, Giacomini F, Raone B, Aprile S, Patrizi

A. Usefulness of dermatoscopy for the early diagnosis of

sebaceous naevus and differentiation from aplasia cutis

congenita. Clin Exp Dermatol 2009;34:e50-2. CrossRef

53. Kim NH, Zell DS, Kolm I, Oliviero M, Rabinovitz HS. The

dermoscopic differential diagnosis of yellow lobularlike

structures. Arch Dermatol 2008;144:962. CrossRef

54. Bomsztyk ED, Garzon MC, Ascherman JA. Postauricular

cerebriform sebaceous nevus: case report and literature

review. Ann Plast Surg 2008;61:637-9. CrossRef

55. Hon KL, Leung AK. Alopecia areata. Recent Pat Inflamm

Allergy Drug Discov 2011;5:98-107. CrossRef

56. Finner AM. Alopecia areata: clinical presentation,

diagnosis, and unusual cases. Dermatol Ther 2011;24:348-54. CrossRef

57. Rudnicka L, Rakowska A, Olszewska M. Trichoscopy: how

it may help the clinician. Dermatol Clin 2013;31:29-41.

58. Inui S, Nakajima T, Nakagawa K, Itami S. Clinical

significance of dermoscopy in alopecia areata: analysis of

300 cases. Int J Dermatol 2008;47:688-93. CrossRef

59. Lallas A, Apalla Z, Tzellos T, Lefaki I. Photoletter to the

editor: dermoscopy in clinically atypical psoriasis. J

Dermatol Case Rep 2012;6:61-2. CrossRef

60. Lallas A, Kyrgidis A, Tzellos TG. Accuracy of dermoscopic

criteria for the diagnosis of psoriasis, dermatitis, lichen

planus and pityriasis rosea. Br J Dermatol 2012;166:1198-205. CrossRef

61. Vázquez-López F, Zaballos P, Fueyo-Casado A, Sánchez-Martín J. A dermoscopy subpattern of plaque-type

psoriasis: red globular rings. Arch Dermatol 2007;143:1612. CrossRef

62. Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Musumeci ML, Massimino D,

Nasca MR. Cutaneous vascular patterns in psoriasis. Int J

Dermatol 2010;49:249-56. CrossRef