DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144327

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REVIEW ARTICLE CME

Use of cephalosporins in patients with immediate penicillin hypersensitivity: cross-reactivity revisited

QU Lee, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Paediatrics)

Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Princess Margaret

Hospital, Laichikok, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr QU Lee (leequnui@gmail.com)

Abstract

A 10% cross-reactivity rate is commonly cited

between penicillins and cephalosporins. However,

this figure originated from studies in the 1960s and

1970s which included first-generation cephalosporins

with similar side-chains to penicillins. Cephalosporins

were frequently contaminated by trace amount

of penicillins at that time. The side-chain

hypothesis for beta-lactam hypersensitivity is

supported by abundant scientific evidence. Newer

generations of cephalosporins possess side-chains

that are dissimilar to those of penicillins, leading

to low cross-reactivity. In the assessment of cross-reactivity

between penicillins and cephalosporins,

one has to take into account the background beta-lactam

hypersensitivity, which occurs in up to 10%

of patients. Cross-reactivity based on skin testing

or in-vitro test occurs in up to 50% and 69% of

cases, respectively. Clinical reactivity and drug

challenge test suggest an average cross-reactivity

rate of only 4.3%. For third- and fourth-generation

cephalosporins, the rate is probably less than 1%.

Recent international guidelines are in keeping with

a low cross-reactivity rate. Despite that, the medical

community in Hong Kong remains unnecessarily

skeptical. Use of cephalosporins in patients with

penicillin hypersensitivity begins with detailed history

and physical examination. Clinicians can choose

a cephalosporin with a different side-chain. Skin

test for penicillin is not predictive of cephalosporin

hypersensitivity, while cephalosporin skin test is

not sensitive. Drug provocation test by experienced

personnel remains the best way to exclude or

confirm the diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity and to

find a safe alternative for future use. A personalised

approach to cross-reactivity is advocated.

The ten per cent myth about beta-lactam

cross-reactivity

Penicillins and cephalosporins are two groups of

widely prescribed antibiotics. They belong to the

class of beta-lactam (BL) antibiotics because both

possess the same BL nucleus. Allergic reactions are

common side-effects of BL antibiotics. Studies in the

1960s and 1970s frequently estimated 10% cross-reactivity

between penicillins and cephalosporins.1 2

However, at least two recent reviews showed much

lower cross-reactivity.3 4 Notably, cross-reactivity is

higher between penicillins and first- and second-generation

cephalosporins compared with third- and

fourth-generation cephalosporins.5 The latter

two groups are considered safe alternatives for

patients with penicillin hypersensitivity.6 The 10%

cross-reactivity rate has recently been questioned as

a medical myth.4 7 Yet until 2005, an influential drug reference such as the British National Formulary

(BNF) abided by the “10% rule”.8 Faced with such

recommendation, an ordinary physician naturally

avoids all BL antibiotics in patients with a history

suggestive of penicillin hypersensitivity.9 The

implications are far-reaching as physicians often

resort to expensive, broad-spectrum antibiotics,

which may induce antibiotic resistance by selecting

out resistant organisms.10 In order to minimise

unnecessary exposure to expensive broad-spectrum

antibiotics with higher toxicities and to preserve

patients’ right to receive commonly prescribed

antibiotics, a better understanding of BL cross-reactivity

is needed. In the following discussion,

the author will review the use of cephalosporins

in patients with immediate hypersensitivity to

penicillins. Mechanism and epidemiology of cross-reactivity

will be discussed, followed by a suggestion

for a pragmatic approach.

By definition, ‘cross-reaction’ between two

substances is “the interaction of an antigen with an

antibody formed against a different antigen with

which the first antigen shares identical or closely

related antigenic determinants”.11 Hence, antigenic

similarity forms the basis of cross-reactivity. Public

hospitals often suggest avoiding all cephalosporins

indiscriminately for patients with penicillin

hypersensitivity, as exemplified by a recent antibiotic

guideline.12 What remains unsettled is how far

the BL nucleus also acts as a common antigenic

determinant. In other words, does structural

similarity in the drug nucleus translate into clinically

relevant allergic reaction?

Mechanism of beta-lactam hypersensitivity

The BL nucleus is probably the only structure

common to penicillins and cephalosporins. What

differentiates between them is that penicillins

possess a 5-membered thiazolidine ring attached

to the BL nucleus while cephalosporins have a

6-membered dihydrothiazine ring. Secondly, while

penicillins have a single 6-positioned side-chain,

cephalosporins have a 3-positioned as well as a

7-positioned side-chain.3

When a BL antibiotic is absorbed into the body,

the BL nucleus undergoes spontaneous opening.

Covalent bonding between the drug and endogenous

protein results in a hapten-protein conjugate.

In case of penicillins, stable protein conjugates

formed include penicilloyl (major) determinants

and other minor determinants.13 For cephalosporin,

however, haptenic determinants are less clear.14

Once inside the body, cephalosporins undergo rapid

fragmentation of the BL nucleus and dihydrothiazine

rings. The resulting unstable metabolites do not

allow haptenisation of proteins.15 In subjects with

BL hypersensitivity, the hapten-protein conjugate

has the capability to activate T-cells and the ensuing

B-cell response. Specific immunoglobulin (Ig) E

antibodies produced by B-cells become attached to

the surface of effector cells such as mast cells and

basophils. Subsequent exposure to the same drug

induces formation of hapten-protein conjugates.

Immediate hypersensitivity is the result of cross-linking

of adjacent surface IgE molecules by the

hapten-protein conjugates that culminates in rapid

degranulation of preformed inflammatory mediators

such as histamine and tryptase.16

Mechanism of cross-reactivity and the side-chain hypothesis

Early cephalosporins before 1980s were

contaminated with trace amounts of penicillin

during the manufacturing process by the

cephalosporium mould. That partly accounted for

the higher cross-reactivity rate between penicillins

and first-generation cephalosporins.14 Cross-reactivity

within penicillins is based on common

antigenic determinants. Antibody binding against

basic structures such as BL ring or penicilloyl

frequently results in higher cross-reactivity rate.

More complex motifs, such as side-chains found

only in certain sub-groups, are associated with

lower cross-reactivity. An in-vitro experiment

has identified two types of T-cells responsible for

penicillin hypersensitivity. The restricted type

is immunologically reactive against a combined

penicilloyl and side-chain structure but exhibits

little cross-reactivity with penicillins with different

side-chains such as amoxicillin or ampicillin. The

broad type does react against different penicillins,

but not against cephalosporins.17

Epitopes (antibody-binding sites) on

penicillin molecules may involve the BL nucleus,

the thiazolidine ring, the side-chain or even the

new antigenic determinant. Side-chain antigenic

determinants account for 42% to 92% of the

penicillin hypersensitivity.18 19 Epitopes on cephalosporin molecules are even more heterogeneous than

penicillin, and involve the whole molecule.20 R1 side-chain

and BL fragment protein conjugates appear to be the major determinants of cephalosporin

hypersensitivity.21 R2 side-chain makes little contribution to cephalosporin hypersensitivity, as it disappears when the BL ring is opened.22

Human studies have provided insight into the

role of similarity in the R1 side-chains in causing

BL cross-reactivity.15 For instance, the 2-amino-2-phenylacetic acid side-chain in ampicillin is also present in first- or second-generation cephalosporins

like cephalexin and cefaclor, respectively, but is

absent in third- or fourth-generation cephalosporins.

Similarly, the same 2-amino-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)

acetic acid side-chain is present in amoxicillin

and cefadroxil but not in new generations of

cephalosporins.16 In another study on selective

amoxicillin hypersensitivity, Miranda et al23 have

shown that oral challenge with cephadroxil, a first-generation

cephalosporin that shared the same side-chain

mentioned above, resulted in a cross-reactivity

of 38%. On the other hand, use of cefamandole, a

second-generation cephalosporin with a different

side-chain from amoxicillin and cephadroxil, did

not result in any cross-reactivity.23 Notwithstanding,

other authors do not accord with the side-chain

hypothesis.24 Fine structure within the side-chain

such as methylene group has also been suggested as

an antigenic determinant common to penicillins and

cephalosporins.25

Background and co-existing drug hypersensitivity

When dealing with potential cross-reactivity

between penicillins and cephalosporins, one should

take into account the background hypersensitivity

rates in unselected population, which range between

0.7% and 10% for penicillins.26 However, among

patients with a history of penicillin allergy, only 10%

to 20% exhibit positive allergic reaction to skin test or

challenge test.27 28 A non-urticarial, maculopapular skin rash is the most common allergic reaction with a

frequency of 1% to 2%. The frequency of anaphylaxis

per penicillin course is 0.01% to 0.05%.29 Similarly,

background hypersensitivity rates for cephalosporins

range between 1% and 10%, while anaphylaxis

occurs in less than 0.02%.30 In other words, patients

with penicillin hypersensitivity may develop non–cross-reacting allergic response to cephalosporins

by coincidence. They are also at increased risk of non-BL hypersensitivity, with a reported rate of 16%

to 23%.31 32 A caveat is that, as local prevalence data are lacking, epidemiological data can only be applied to the Hong Kong situation by extrapolation.

Cross-reactivity based on cephalosporin skin testing

Skin test is an in-vivo method used to diagnose

IgE-mediated allergic response. Substantial cross-reactivity

in terms of skin testing exists between penicillins and first-generation cephalosporins. In the

1970s, Assem and Vickers33 studied 24 patients with

penicillin hypersensitivity of which 11 (46%) showed

positive intradermal test to cephaloridine; however,

this reaction was not observed in any of the patients

without penicillin hypersensitivity.33 Dash2 studied 100 patients with clinical reaction to penicillin

and demonstrated positive cephalosporin skin test

in 11 (11%) patients. However, seven (9.3%) of 75

control subjects without penicillin hypersensitivity

also tested positive.2 In another study in the 1980s,

Sullivan et al34 recruited 74 patients with penicillin

hypersensitivity confirmed by positive skin prick

test (SPT). Of these, 38 (50%) also exhibited a

positive SPT to cephalothin, another first-generation

cephalosporin.34 Audicana et al35 studied 34 patients allergic to penicillin and found that five (14%) had

positive skin test to cephalexin, a first-generation cephalosporin, but none to ceftazidime, a third-generation

cephalosporin. Romano et al36 studied 128 adult subjects with a history of immediate

penicillin hypersensitivity; positive cephalosporin skin test was observed in 11% of them. Of the 128 subjects, 101 (94 skin test negative and 7 skin test positive for cephalosporins) who accepted the challenge could tolerate oral cefuroxime axetil and intramuscular ceftriaxone.36 Although controlled trial is not possible, the implication is that cephalosporins can be safely given to patients with a history of penicillin hypersensitivity but who have

negative cephalosporin skin test.

Cross-reactivity based on in-vitro tests

Substantial in-vitro cross-reactivity also

exists between penicillins and first-generation

cephalosporins. In an early study in 1960s, Abraham

et al37 were able to demonstrate haemagglutination

antibody against cephalothin (titre of 1:8 or greater)

in 22 (69%) of 32 patients who had been given

penicillin but denied a history of cephalothin

therapy. A subsequent adsorption study using

penicilloic acid-solid phase by Zhao et al25 further

identified cross-reacting specific IgE antibodies

against both benzylpenicillin and cephalothin.

Recently, Liu et al38 employed radioallergosorbent

test to identify specific IgE antibodies against

penicillins and cephalosporins in 420 subjects with

penicillin hypersensitivity; cross-reacting specific

IgE antibodies occurred in 22.6% of the subjects.

Specific cephalosporin IgE antibodies were present in

27.1% of those with specific penicillin IgE antibodies,

compared with 14.6% in those without specific

penicillin IgE antibodies.38 However, in the absence

of cross-linking, demonstration of antibodies cannot

be equated with clinical reactivity.2

Clinical reaction to cephalosporins in patients with a history of penicillin hypersensitivity

As skin test and in-vitro test are often inadequate

for confirmation of cephalosporin hypersensitivity,

one has to rely on a provocation test or the result

of drug exposure. In an early review of 701 patients

with a history of penicillin hypersensitivity, Petz39

reported an 8.1% reactivity rate to first- or second-generation

cephalosporins, compared with 1.9% among those without penicillin hypersensitivity. In

another cohort study in the 1980s by Solley et al,40

178 patients with a history of penicillin allergy were

given cephalosporins. Positive reaction resulted in

two patients, equivalent to a clinical cross-reactivity

rate of 1.1%.40 Goodman et al41 reviewed the medical records of 413 patients with a self-reported history of penicillin allergy who underwent anaesthetic

procedures that included antibiotic therapy. Only one patient (0.24%) probably developed cross-reactivity

to cephalexin, a first-generation cephalosporin.41

Despite the retrospective nature and the lack of confirmatory tests, the low clinical cross-reactivity

is reassuring.

Fonacier et al42 reviewed 83 patients with

penicillin hypersensitivity who were subsequently

given cephalosporins. Seven (8.4%) of them

developed an adverse drug reaction. A definite

history of penicillin hypersensitivity was found in

six (85.7%) of the seven patients. Eleven (13.3%)

patients with penicillin hypersensitivity also

reported hypersensitivity reaction to other drugs

such as non-BL antibiotics and codeine. Regarding

the types of cephalosporin, clinical cross-reactivity

rates between penicillin and first-, second-, third-,

and fourth-generation cephalosporins are 4.6%,

50%, 10.5% and 0%, respectively. Small sample size

and potential recall bias undermine the reliability of

the study. The role of side-chain is highlighted by a

4-fold increase in the cross-reactivity rate between

penicillins and cephalosporins with similar amino-benzyl ring side-chain.

In a large prospective study by Atanasković-Marković et al43 that included 644 children with a

history of hypersensitivity reaction to penicillins,

rate of cross-reactivity to cephalosporins was

31.5%. If the generations of cephalosporins were

taken into account, the cross-reactivity rate with

aminopenicillins differed by 100-fold, ranging from

0.3% to 0.7% in third-generation cephalosporins to

around 32.4% to 38.5% in first- or second-generation

cephalosporins, respectively. This, again, illustrates

the relevance of side-chain in cross-reactivity. An

interesting corollary is that, in patients with negative

skin test to penicillins or cephalosporins, 0% to

1.8% of patients showed positive drug challenge to

the test drug. Hence the false-negative rate of skin

test is quite low. On the other hand, as patients with

positive skin test were not further challenged with

drugs to confirm clinical hypersensitivity, the true-positive

rate cannot be ascertained.

A 5-year retrospective study by Apter et al32

reviewed 534 810 patients in the United Kingdom

who received a penicillin followed by cephalosporin

of which 64% were tested with first-generation

cephalosporins. The authors compared 3920 patients

with allergy-like events (ALE) within 30 days of

receiving penicillin with 530 890 patients without

ALE. Among 3920 patients with ALE after receiving

penicillin, 1% cross-reacted with cephalosporins. The

unadjusted risk ratios for ALE after the subsequent

cephalosporin and sulphonamide challenges were

10.0 (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.4-13.6) and

7.2 (95% CI, 3.8-13.5), respectively, suggesting that

patients allergic to penicillin may have an increased

tendency for drug hypersensitivity via a mechanism

other than cross-reactivity.

In another retrospective study, Daulat et al44

reviewed medical records of 606 patients with a

history of penicillin allergy who were subsequently

given a cephalosporin. Confirmatory penicillin

skin testing was not reported. Clinical allergy

occurred in only one patient given cefazolin, a first-generation

cephalosporin. This is tantamount to

a cross-reactivity rate of 0.165%. As drug allergy

was suspected from diagnostic coding only, true

penicillin allergy, and hence cephalosporin cross-reactivity,

might have been higher.

In a landmark meta-analysis in 2007, Pichichero

and Casey15 reviewed nine studies that compared

allergic reaction rate to cephalosporins in patients

with or without penicillin allergy. Among 47 284

patients with a history of penicillin allergy alone, the

odds ratio (OR) for cephalosporin cross-reactivity

in general was 2.63 (95% CI, 2.11-3.28; P<0.00001).

However, the increased cross-reactivity rate was

mainly due to first-generation cephalosporins, as

the corresponding ORs for first-, second-, and third-generation

cephalosporins were 4.79 (95% CI, 3.71-6.17; P<0.00001), 1.13 (95% CI, 0.61-2.12; P=0.70),

and 0.45 (95% CI, 0.18-1.13; P=0.09), respectively.

There was actually a trend towards decreased risk of

cross-reactivity to third-generation cephalosporins,

although the result did not reach statistical

significance.

Clinical reaction to cephalosporins in patients with penicillin hypersensitivity confirmed by investigations

In a cohort study by Solley et al,40 none of the 27

patients with a history of penicillin allergy and

a positive penicillin skin test developed clinical

reactivity to cephalosporins. On the contrary, two

of the 151 patients with allergic history but negative

penicillin skin test reacted to cephalosporins, putting

to doubt the value of penicillin skin test in predicting

cross-reactivity to cephalosporins.40 In another

small cohort study by Blanca et al,45 19 patients with

confirmed penicillin hypersensitivity were given

parenteral cephamandole, a second-generation

cephalosporin, followed by oral cephaloridine, a

first-generation cephalosporin, if the former was

tolerated. Two (10.5%) of the 19 patients cross-reacted

with cephamandole while all the remaining

17 patients tolerated cephaloridine.

Sastre et al24 subjected 16 patients with

selective amoxicillin hypersensitivity confirmed

by skin test or drug challenge with cephadroxil, a

first-generation cephalosporin. Two (12%) were

found to be cross-reactors.24 Novalbos et al46

recruited 41 patients with a history of penicillin

hypersensitivity confirmed by either skin test or

drug challenge. Patients were then challenged with

three cephalosporins (cephazoline, cefuroxime and

ceftriaxone) with side-chains which were different

from that of penicillin. None of them cross-reacted

with the cephalosporins.46 Hameed and Robinson47

recruited 158 patients with positive penicillin

test. Seven (4.4%) of them developed immediate

hypersensitivity when given cephalosporins. None of

the cephalosporins was from the third generation.47

There is a lack of published reports on anaphylactic

reaction to cephalosporins in children with a history

of anaphylaxis to penicillins, and only a few such

reports in adults have been published.47

Macy and Burchette48 studied 83 patients with a

history of adverse reaction to penicillin confirmed by

skin test. Post–skin test exposure to cephalosporins in

42 resulted in adverse reaction in one, amounting to

2.4% cross-reactivity rate. The corresponding figure

for non-BL was eight (10.8%) out of 74, suggesting

that in patients allergic to penicillin, cross-reactivity

for non-BLs may be even higher than that for BLs.48 This

study and the one by Apter et al32 have significant

implications for practitioners who routinely employ

non-BL antibiotics for patients with penicillin

hypersensitivity.

In a preoperative assessment clinic, Park et

al49 recruited 1072 patients with a history of BL

allergy for penicillin skin testing. Among the 999

patients who underwent the skin test, 43 had a

positive skin test for penicillin and three of those 43

eventually received cefazolin. None developed cross-reactivity.49 Ahmed et al50 reviewed 173 children

with a history of penicillin hypersensitivity, with or

without a skin test, who underwent cephalosporin

challenge. None among those with positive skin test

showed reactivity. However, one (0.7%) of the 152

patients with negative skin test had an immediate

allergic reaction after cephalexin, underscoring the

lack of predictive power of the penicillin skin test.50

In a meta-analysis by Pichichero and Casey,15

1831 patients with a history of penicillin allergy

also received penicillin skin test. Compared with

patients with negative skin test, the OR for cross-reactivity

to any cephalosporin for patients with

positive results was 1.48 (95% CI, 0.64-3.41; P=0.36).

Corresponding ORs for first-, second-, and third-generation

cephalosporins were 4.13 (95% CI, 0.70-24.51; P=0.11), 1.33 (95% CI, 0.32-5.52; P=0.69),

and 0.75 (95% CI, 0.15-3.66; P=0.72), respectively.15

There was a trend towards increased risk for first-generation

cephalosporins, although the result did not reach statistical significance.

Studies on cephalosporin drug challenge in

patients with a history of penicillin hypersensitivity

have several inherent limitations. Firstly, retrospective

studies are subjected to recall bias. Secondly,

the so-called ‘positive reaction’ may include ‘nocebo

effects’, ie untoward effects after administration of an

inert substance, which may occur in around 27% of

subjects.51 Thirdly, as most studies excluded patients

with positive penicillin skin test, investigators had

no way to tell whether these patients could actually

tolerate cephalosporins. Lastly, most studies of

cephalosporin challenge were performed in an open,

uncontrolled manner. Patients with penicillin allergy

who may have underlying multiple drug allergy

syndrome will be missed in the absence of a control

arm, such as non-BL group.52

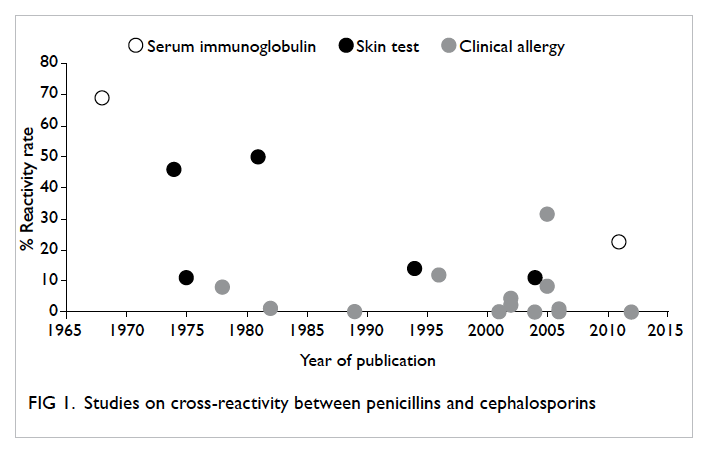

Ten per cent cross-reactivity: an over-estimation

Review of published studies, as described above,

shows that cross-reactivity between penicillins and

cephalosporins, if restricted to clinical reaction

or positive drug challenge, varies between 0% and

31.5% (Fig 1). Among the 14 studies that included a total of 6464 patients with penicillin hypersensitivity,

279 showed clinical reactivity or positive challenge

to cephalosporins, resulting in an average cross-reactivity

rate of 4.32%. Corresponding figures for patients with a history of penicillin allergy alone

and those confirmed by investigations are 4.34% and

3.76%, respectively. Studies reporting rates higher

than 10% are mainly those involving first- or second-generation

cephalosporins, especially when in-vitro or skin tests were employed. It must be emphasised

that although cross-reactivity is substantial with first-generation

cephalosporins (up to 32%), it is less than 1% for third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins.

A probable reason for the low cross-reactivity

stems from the fact that, despite having the same

BL nucleus, penicillins and cephalosporins are

immunologically different. If the BL nucleus is

the common antigenic determinant, one should

expect a very high cross-reactivity. However, this

is not the case because the BL ring opens in the

process of metabolism to form major or minor

determinants. Secondly, newer generations of

cephalosporin do not share similar side-chains with

penicillins, hence cross-reactivity will, generally,

not occur. Thirdly, among patients with alleged

penicillin hypersensitivity, less than 10% show

genuine hypersensitivity. The majority of cases may

suffer from transient adverse reaction followed by

subsequent tolerance to cephalosporins.7

Despite current recognition of the low cross-reactivity

rate, international guidelines are not

unanimous in their recommendations regarding

the use of cephalosporins in patients with penicillin

hypersensitivity. A recent practice parameter from

a Joint Task Force in the United States stated that

“most patients with a history of penicillin allergy

tolerate cephalosporins”.10 If patients with positive

penicillin skin test are given cephalosporins,

around 2% may cross-react, including some with

anaphylactic reactions. If a clinician chooses not to

skin test a patient with a history of penicillin allergy

but directly prescribe a cephalosporin, the chance

of developing a reaction is probably less than 1%.

In treating otitis media in children with penicillin

allergy, the American Academy of Pediatrics simply

suggested prescribing, rather than avoiding, either

second- or third-generation cephalosporins.53 Basing

on dissimilarity in chemical structures, the Academy

considered cross-reactivity between penicillin and

second- or third-generation cephalosporins to be

‘highly unlikely’.

A relatively conservative approach is adopted

by the Infectious Diseases Society of America

(IDSA). In the 2012 clinical practice guideline for

bacterial rhinosinusitis, the IDSA recommended

third-generation cephalosporins only for patients

with non–type I penicillin allergy. Non-BL antibiotics

were recommended for those with type I penicillin

allergy.54 Even more conservative is the British

Medical Association; in the 2014 edition, the BNF

advised against using cephalosporins in patients

with penicillin hypersensitivity. Nevertheless, if no

other alternatives are available, third- and fourth-generation

cephalosporins can be used, albeit with

caution.55

Skepticism still lingers within the medical community

in Hong Kong. For instance, a recent public

hospital antibiotic guideline does not differentiate

between different generations of cephalosporins,

but treats all cephalosporins as having the potential

to cross-react with penicillins.56 The IMPACT

guideline in Hong Kong has aptly pointed out a deep-rooted

preoccupation with cross-reactivity among

the medical profession. The guideline suggests that

“second, third and fourth generation cephalosporins

have negligible cross-reactivity with penicillin”.

However, it also raises a common concern that

contra-indications indicated in product inserts have

resulted in “medico-legal implications when using

cephalosporins in patients with penicillin allergy”.57

This concern is understandable but unfounded, for

two reasons. Firstly, a legal case appealed to the New

Jersey Supreme Court in 1998 has come to the final

decision that product inserts alone do not establish

a standard of care.3 Secondly, a review of the inserts

shows that, rather than contra-indicating the use

of cephalosporins, pharmaceutical companies only

issue words of caution in patients with penicillin

allergy.58 59

Pragmatic approach to cross-reactivity

For patients with suspected penicillin

hypersensitivity, one should begin with careful

history and physical examination to establish the

likelihood of adverse drug reaction. Clinicians will

not do justice by simply avoiding all cephalosporins

in patients with so-called penicillin hypersensitivity.

Injudicious use of non-BL antibiotics without

precaution is falsely reassuring and will expose

patients with allergic tendency to further drug

hypersensitivity.

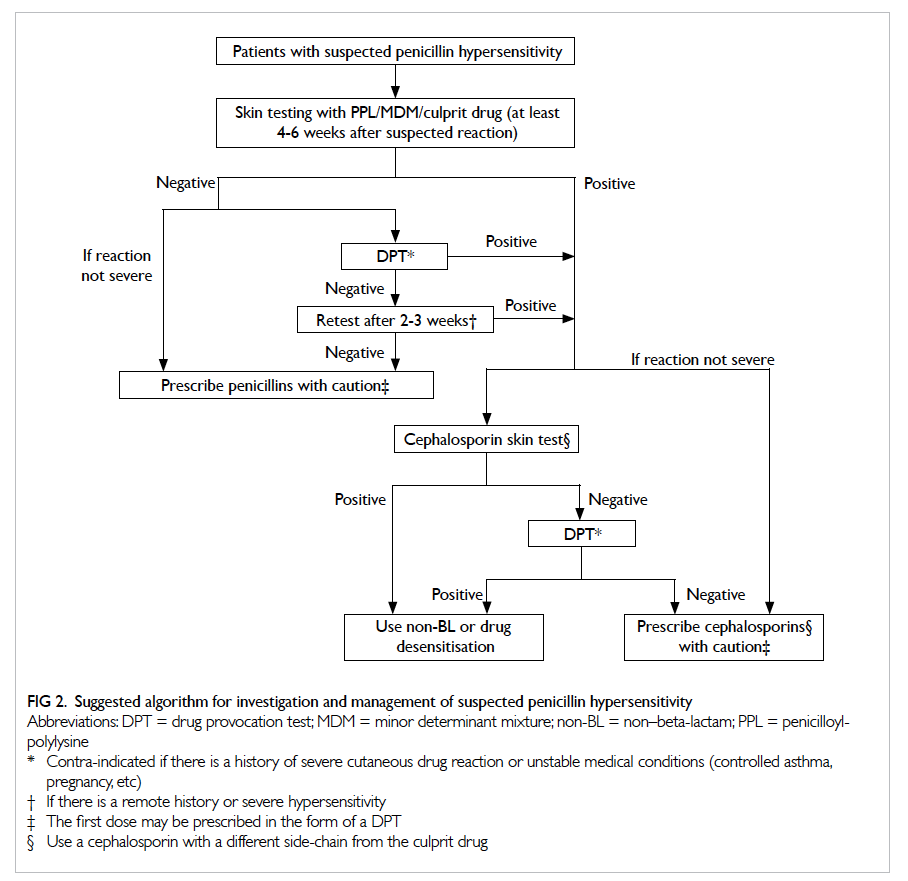

Allergological investigations should preferably

be done 4 to 6 weeks after resolution of adverse

drug reaction.60 One should start from skin testing

to confirm penicillin hypersensitivity. Ideally, skin

test reagents should include penicilloyl polylysine

(PPL) and minor determinant mixture (MDM).

Unfortunately, the two major manufacturers,

Allergopharma (Hamburg, Germany) and Hollister-Stier (Spokane, WA, US) ceased production of PPL

and MDM in 2004. Although Diater (Madrid, Spain)

has launched the production of PPL and MDM

since 2003, the reagents have not gained widespread

popularity in Hong Kong.61 Besides, diagnosis of

selective reaction to a single BL requires a long

algorithm, which begins testing with PPL and MDM,

followed by the culprit drug.5 This may be tedious

and time-consuming in daily clinical practice. For

pragmatic purposes, it is often the culprit drug and/or a potentially safe alternative that will be tested

and prescribed. Non-irritating concentration of the

culprit drug should be employed for skin testing.62

Patients with negative penicillin skin test may

undergo supervised drug provocation test (DPT) of

the culprit drug.3 The aim of DPT is to exclude or

confirm the diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity and to

find a safe alternative for future use. Drug provocation

test generally has a high negative predictive value of

94% to 98%. A caveat is that anaphylactic reactions

can still occur among a few cross-reacting patients.

Hence, DPT must be performed by experienced

personnel in a setting with resuscitation facilities.60

Patients with remote or severe hypersensitivity may

be re-tested 2 to 4 weeks later to exclude a small but

possible risk of re-sensitisation after initial negative

testing. Contra-indications to DPT include a history

of severe cutaneous drug reactions (eg Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis),

severe anaphylaxis or certain medical conditions

(eg uncontrolled asthma or pregnancy).63 In the

absence of severe or recent immediate penicillin

hypersensitivity, patients may choose to receive

penicillin directly without skin testing.10 To further

ensure drug safety, the first dose may be divided into

incremental steps similar to DPT.

Patients who have a history of severe penicillin

hypersensitivity, a positive penicillin skin test or DPT

may resort to cephalosporins. However, a positive

penicillin skin test does not predict cross-reactivity

with cephalosporin.30 50 Clinicians may perform

skin tests using a cephalosporin with a different side-chain to guide clinical use.10 Unfortunately, the diagnostic accuracy of cephalosporin skin test is difficult to establish.5 Studies generally have shown low sensitivity and positive predictive value.64 65 Nevertheless, skin test for BL hypersensitivity is still

considered ‘good’ by the International Consensus in 2014.60 Patients with negative cephalosporin skin test should pass a DPT before finally receiving a cephalosporin. Patients who fail the DPT may be given a non-BL antibiotic or undergo desensitisation, if the cephalosporin is essential.60 A suggested algorithm for investigation and management of suspected immediate penicillin hypersensitivity is

summarised in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Suggested algorithm for investigation and management of suspected penicillin hypersensitivity

Conclusion

The available evidence to date does not support

the notion of a 10% cross-reactivity rate between

penicillins and cephalosporins. Above all, 10% is

an oversimplified and indiscriminate generalisation

of cross-reactivity. Scientific evidence supports the

side-chain hypothesis and a low cross-reactivity rate.

Clinicians should adopt a personalised approach

towards BL cross-reactivity. Finally, future research

on the local prevalence of BL hypersensitivity and

cross-reactivity is needed.

Declaration

No conflicts of interests were declared by the author.

References

1. Petz LD, Fudenberg HH. Coombs-positive hemolytic

anemia caused by penicillin administration. N Engl J Med

1966;274:171-8. CrossRef

2. Dash CH. Penicillin allergy and the cephalosporins. J

Antimicrob Chemother 1975;1(3 Suppl):107-18. CrossRef

3. DePestel DD, Benninger MS, Danziger L, et al.

Cephalosporin use in treatment of patients with penicillin

allergies. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2008;48:530-40. CrossRef

4. Campagna JD, Bond MC, Schabelman E, Hayes BD. The

use of cephalosporins in penicillin-allergic patients: a

literature review. J Emerg Med 2012;42:612-20. CrossRef

5. Torres MJ, Blanca M, Fernandez J, et al. Diagnosis of

immediate allergic reactions to beta-lactam antibiotics.

Allergy 2003;58:961-72. CrossRef

6. Prematta T, Shah S, Ishmael FT. Physician approaches to

beta-lactam use in patients with penicillin hypersensitivity.

Allergy Asthma Proc 2012;33:145-51. CrossRef

7. Herbert ME, Brewster GS, Lanctot-Herbert M. Medical

myth: ten percent of patients who are allergic to penicillin

will have serious reactions if exposed to cephalosporins.

West J Med 2000;172:341. CrossRef

8. British Medical Association and the Royal Pharmaceutical

Society of Great Britain. British National Formulary BNF

49 March 2005. London: BMJ Books; 2005.

9. Solensky R, Earl HS, Gruchalla RS. Clinical approach to

penicillin-allergic patients: a survey. Ann Allergy Asthma

Immunol 2000;84:329-33. CrossRef

10. Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters; American

Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; American

College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; Joint Council

of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Drug allergy: an

updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol

2010;105:259-73. CrossRef

11. Cross reaction. In: Anderson DM, editor. Dorland’s

illustrated medical dictionary. 31st ed. Philadelphia: W.B.

Saunders; 2007.

12. Kowloon West Cluster Antibiotic Subcommittee. KWC

Antimicrobial Therapy Guide 2012, Second Edition [cited

2014 June 5]. Available from: https://gateway.ha.org.hk/f5-w-687474703a2f2f706d682e686f6d65$$/sites/mg/General/KWC%20Antimicrobial%20Thearpy%20

Guide%202012.pdf. Accessed Jun 2014.

13. Park B, Sanderson J, Naisbitt D. Drugs as haptens,

antigens, and immunogens. In: Pichler WJ, editor. Drug

hypersensitivity. Basel: Karger; 2007: 55-65. CrossRef

14. Kelkar PS, Li JT. Cephalosporin allergy. N Engl J Med

2001;345:804-9. CrossRef

15. Pichichero ME, Casey JR. Safe use of selected

cephalosporins in penicillin-allergic patients: a meta-analysis.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007;136:340-7. CrossRef

16. Torres M, Mayorga C, Blanca M. Urticaria and anaphylaxis

due to betalactams (penicillins and cephalosporins). In:

Pichler WJ, editor. Drug hypersensitivity. Basel: Karger;

2007: 190-203. CrossRef

17. Mauri-Hellweg D, Zanni M, Frei E, et al. Cross-reactivity

of T cell lines and clones to beta-lactam antibiotics. J

Immunol 1996;157:1071-9.

18. Mayorga C, Obispo T, Jimeno L, et al. Epitope mapping

of beta-lactam antibiotics with the use of monoclonal

antibodies. Toxicology 1995;97:225-34. CrossRef

19. Torres MJ, Romano A, Mayorga C, et al. Diagnostic

evaluation of a large group of patients with immediate

allergy to penicillins: the role of skin testing. Allergy

2001;56:850-6. CrossRef

20. Pham NH, Baldo BA. beta-Lactam drug allergens: fine

structural recognition patterns of cephalosporin-reactive

IgE antibodies. J Mol Recognit 1996;9:287-96. CrossRef

21. Sánchez-Sancho F, Perez-Inestrosa E, Suau R, et al.

Synthesis, characterization and immunochemical

evaluation of cephalosporin antigenic determinants. J Mol

Recognit 2003;16:148-56. CrossRef

22. Blanca M, Romano A, Torres MJ, et al. Update on the

evaluation of hypersensitivity reactions to betalactams.

Allergy 2009;64:183-93. CrossRef

23. Miranda A, Blanca M, Vega JM, et al. Cross-reactivity

between a penicillin and a cephalosporin with the same

side chain. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1996;98:671-7. CrossRef

24. Sastre J, Quijano LD, Novalbos A, et al. Clinical cross-reactivity

between amoxicillin and cephadroxil in patients

allergic to amoxicillin and with good tolerance of penicillin.

Allergy 1996;51:383-6. CrossRef

25. Zhao Z, Baldo BA, Rimmer J. beta-Lactam allergenic

determinants: fine structural recognition of a cross-reacting

determinant on benzylpenicillin and cephalothin.

Clin Exp Allergy 2002;32:1644-50. CrossRef

26. Idsoe O, Guthe T, Willcox RR, de Weck AL. Nature and

extent of penicillin side-reactions, with particular reference

to fatalities from anaphylactic shock. Bull World Health

Organ 1968;38:159-88.

27. Graff-Lonnevig V, Hedlin G, Lindfors A. Penicillin

allergy—a rare paediatric condition? Arch Dis Child

1988;63:1342-6. CrossRef

28. Park MA, Li JT. Diagnosis and management of penicillin

allergy. Mayo Clin Proc 2005;80:405-10. CrossRef

29. Shepherd GM. Allergy to β-lactam antibiotics. Immunol

Allergy Clin N Am 1991;11:611-33.

30. Annè S, Reisman RE. Risk of administering cephalosporin

antibiotics to patients with histories of penicillin allergy.

Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1995;74:167-70.

31. Khoury L, Warrington R. The multiple drug allergy

syndrome: a matched-control retrospective study in

patients allergic to penicillin. J Allergy Clin Immunol

1996;98:462-4. CrossRef

32. Apter AJ, Kinman JL, Bilker WB, et al. Is there cross-reactivity

between penicillins and cephalosporins? Am J

Med 2006;119:354.e11-9.

33. Assem ES, Vickers MR. Tests for penicillin allergy in man.

II. The immunological cross-reaction between penicillins

and cephalosporins. Immunology 1974;27:255-69.

34. Sullivan TJ, Wedner HJ, Shatz GS, Yecies LD, Parker CW.

Skin testing to detect penicillin allergy. J Allergy Clin

Immunol 1981;68:171-80. CrossRef

35. Audicana M, Bernaola G, Urrutia I, et al. Allergic reactions

to betalactams: studies in a group of patients allergic

to penicillin and evaluation of cross-reactivity with

cephalosporin. Allergy 1994;49:108-13. CrossRef

36. Romano A, Guéant-Rodriguez RM, Viola M, Pettinato

R, Guéant JL. Cross-reactivity and tolerability of

cephalosporins in patients with immediate hypersensitivity

to penicillins. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:16-22. CrossRef

37. Abraham GN, Petz LD, Fudenberg HH.

Immunohaematological cross-allergenicity between

penicillin and cephalothin in humans. Clin Exp Immunol

1968;3:343-57.

38. Liu XD, Gao N, Qiao HL. Cephalosporin and penicillin

cross-reactivity in patients allergic to penicillins. Int J Clin

Pharmacol Ther 2011;49:206-16. CrossRef

39. Petz LD. Immunologic cross-reactivity between penicillins

and cephalosporins: a review. J Infect Dis 1978;137

Suppl:S74-S79. CrossRef

40. Solley GO, Gleich GJ, Van Dellen RG. Penicillin allergy:

clinical experience with a battery of skin-test reagents. J

Allergy Clin Immunol 1982;69:238-44. CrossRef

41. Goodman EJ, Morgan MJ, Johnson PA, Nichols BA, Denk

N, Gold BB. Cephalosporins can be given to penicillin-allergic

patients who do not exhibit an anaphylactic

response. J Clin Anesth 2001;13:561-4. CrossRef

42. Fonacier L, Hirschberg R, Gerson S. Adverse drug reactions

to a cephalosporins in hospitalized patients with a history

of penicillin allergy. Allergy Asthma Proc 2005;26:135-41.

43. Atanasković-Marković M, Velicković TC, Gavrović-Jankulović M, Vucković O, Nestorović B. Immediate allergic reactions to cephalosporins and penicillins and

their cross-reactivity in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol

2005;16:341-7. CrossRef

44. Daulat S, Solensky R, Earl HS, Casey W, Gruchalla RS.

Safety of cephalosporin administration to patients with

histories of penicillin allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol

2004;113:1220-2. CrossRef

45. Blanca M, Fernandez J, Miranda A, et al. Cross-reactivity

between penicillins and cephalosporins: clinical and

immunologic studies. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1989;83:381-5. CrossRef

46. Novalbos A, Sastre J, Cuesta J, et al. Lack of allergic cross-reactivity

to cephalosporins among patients allergic to

penicillins. Clin Exp Allergy 2001;31:438-43. CrossRef

47. Hameed TK, Robinson JL. Review of the use of

cephalosporins in children with anaphylactic reactions

from penicillins. Can J Infect Dis 2002;13:253-8.

48. Macy E, Burchette RJ. Oral antibiotic adverse reactions

after penicillin skin testing: multi-year follow-up. Allergy

2002;57:1151-8. CrossRef

49. Park M, Markus P, Matesic D, Li JT. Safety and effectiveness

of a preoperative allergy clinic in decreasing vancomycin

use in patients with a history of penicillin allergy. Ann

Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006;97:681-7. CrossRef

50. Ahmed KA, Fox SJ, Frigas E, Park MA. Clinical outcome

in the use of cephalosporins in pediatric patients with a

history of penicillin allergy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol

2012;158:405-10. CrossRef

51. Liccardi G, Senna G, Russo M, et al. Evaluation of the

nocebo effect during oral challenge in patients with

adverse drug reactions. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol

2004;14:104-7.

52. American Academy of Allergy Asthma & Immunology.

Work group report: cephalosporin administration to

patients with a history of penicillin allergy May, 2009 [cited

2014 April 6]. Available from: https://www.aaaai.org/Aaaai/media/MediaLibrary/PDF%20Documents/Practice%20and%20Parameters/Cephalosporin-administration-2009.

pdf. Accessed Apr 2014.

53. Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T, et al. The

diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics

2013;131:e964-99. CrossRef

54. Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, et al. IDSA clinical

practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in

children and adults. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54:e72-e112. CrossRef

55. British Medical Association and the Royal Pharmaceutical

Society of Great Britain. British National Formulary BNF

66 September 2013. London: BMJ Books; 2014.

56. Ching B. Hospital Authority guideline on known drug

allergy checking. Hong Kong: Hospital Authority; 2013.

57. Reducing bacterial resistance with IMPACT—Interhospital

Multi-disciplinary Programme on Antimicrobial

ChemoTherapy. 4th ed. Hong Kong: Centre for Health

Protection; 2012.

58. Ceftriaxone for Injection, USP [package insert] Lake

Forest, IL: Hospira; [updated Dec 2010; cited 2014 June

22]. Available from: http://www.hospira.com/Images/EN-2726_32-91495_1.pdf. Accessed Jun 2014.

59. Cefotaxime for Injection, USP [package insert]

Bridgewater, NJ: Sanofi; [updated Feb 2014; cited 2014 June

22]. Available from: http://products.sanofi.us/claforan/claforan.pdf. Accessed Jun 2014.

60. Demoly P, Adkinson NF, Brockow K, et al. International

Consensus on drug allergy. Allergy 2014;69:420-37. CrossRef

61. Romano A, Viola M, Bousquet PJ, et al. A comparison of the

performance of two penicillin reagent kits in the diagnosis

of beta-lactam hypersensitivity. Allergy 2007;62:53-8. CrossRef

62. Brockow K, Garvey LH, Aberer W, et al. Skin test

concentrations for systemically administered drugs—an

ENDA/EAACI Drug Allergy Interest Group position

paper. Allergy 2013;68:702-12. CrossRef

63. Aberer W, Bircher A, Romano A, et al. Drug provocation

testing in the diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity reactions:

general considerations. Allergy 2003;58:854-63. CrossRef

64. Romano A, Gaeta F, Valluzzi RL, Alonzi C, Viola M,

Bousquet PJ. Diagnosing hypersensitivity reactions to

cephalosporins in children. Pediatrics 2008;122:521-7. CrossRef

65. Yoon SY, Park SY, Kim S, et al. Validation of the

cephalosporin intradermal skin test for predicting

immediate hypersensitivity: a prospective study with drug

challenge. Allergy 2013;68:938-44. CrossRef