Hong

Kong Med J 2014 Oct;20(5):366–70 | Epub 1

Aug 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144232

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Limitation of radiological T3 subclassification

of

rectal cancer due to paucity of mesorectal fat in

Chinese patients

Esther MF Wong, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology)1;

Bill MH Lai, MB, BS, FRCR1; Vincent KP Fung, MB, BS,

FRCR1; Hester YS Cheung, FRACS, FHKAM (Surgery)2;

WT Ng, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology)3; Ada LY Law, FHKCR,

FHKAM (Radiology)3; Alta YT Lai, MB, BS1;

Jennifer LS Khoo, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology)1

1Department of Radiology,

Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

2Department of Surgery,

Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

3Department of Oncology,

Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Esther MF Wong (esthermfwong@gmail.com)

Abstract

Objectives: To describe

the thickness of mesorectal

fat in local Chinese population and its impact on

rectal cancer staging.

Design: Case series.

Setting: Two local

regional hospitals in Hong Kong.

Patients: Consecutive

patients referred for

multidisciplinary board meetings from January to

October 2012 were selected.

Main outcome measures:

Reports of cases

that had undergone staging magnetic resonance

imaging for histologically proven rectal cancer

were retrospectively retrieved and reviewed by

two radiologists. All magnetic resonance imaging

examinations were acquired with 1.5T magnetic

resonance imaging. Measurements were made

by agreement between the two radiologists. The

distance in mm was obtained in the axial plane at

levels of 5 cm, 7.5 cm, and 10 cm from the anal verge.

Four readings were obtained at each level, namely,

anterior, left lateral, posterior, and right lateral

positions.

Results: A total of 25

patients (16 males, 9 females)

with a median age of 69 (range, 38-84) years were

included in the study. Mean thickness of the

mesorectal fat at 5 cm, 7.5 cm, and 10 cm from

the anal verge was 3.1 mm (standard deviation, 3.0

mm), 9.8 mm (5.3 mm), and 11.8 mm (4.2 mm),

respectively. The proportions of patients with mean mesorectal

fat thickness of <15 mm were

100%, 84%, and 75% at 5 cm, 7.5 cm, and 10 cm

from the anal verge, respectively. The thickness of

mesorectal fat was the least anteriorly, and <15 mm at all

three arbitrary levels (P<0.001).

Conclusion: The

thickness of mesorectal fat was

<15 mm in the majority of patients and

in most positions. Tumours invading 10 mm

beyond the serosa on magnetic resonance imaging

may paradoxically threaten the circumferential

resection margin in Chinese patients. Use of T3

subclassification of rectal cancer in Chinese patients

may be limited.

New knowledge added by this

study

- Paucity of mesorectal fat in Chinese populations: tumours invading 10 mm beyond the serosa on magnetic resonance imaging may threaten the circumferential resection margin in the majority of patients.

- The mesorectal fat is thinnest in the anterior portion. Tumours in the anterior wall have a higher chance of infiltrating the mesorectal fascia versus those located in other positions.

- The T3 subclassification of rectal cancer should be used with caution in Chinese patients.

Introduction

Rectal cancer is associated with a high

risk of distant

metastases as well as local recurrence. The reported

local recurrence rate after surgical treatment was

up to 32% in some older literatures.1

Recently,

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has emerged as a powerful local

staging tool which also helps to

guide subsequent management plan.2

3 The status of

circumferential resection margin (CRM), presence of

lymph node metastasis, and location of the tumour,

all of which can be predicted on MRI, are important

prognostic factors for pelvic disease recurrence after treatment

with curative intent (local failure).4

5 6

The depth of extramural penetration of the

tumour has been shown to be an independent

prognostic factor.7

According to the European

Society for Medical Oncology guidelines,8

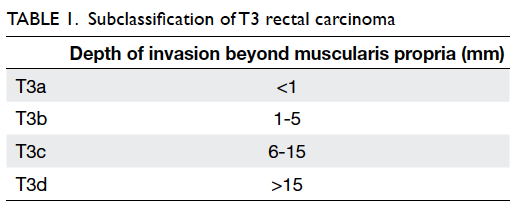

T3 disease

is subclassified into T3a, T3b, T3c, and T3d based

on the depth of invasion beyond the muscularis

propria (Table

1). Magnetic resonance imaging is

also highly accurate in predicting the actual depth of

this invasion.9 Currently,

patients with disease more

advanced than T3b are recommended to receive

induction therapy prior to surgery.

Another factor that potentially affects the

disease status is the thickness of the mesorectal

fat which, for the sake of this discussion, shall be

defined as the distance between the serosa and

mesorectal fascia. The word ‘perirectal fat’ is used

interchangeably with ‘mesorectal fat’. We are of

the opinion that the word ‘mesorectal fat’ better

conceptualises compartmentalised fat within the

mesorectal fascia and is, thus, selected for use in this

article.

In our experience, the mesorectal fat is

rather

thin in Chinese patients. It is not uncommon to

encounter early T3 (T3a/b) disease with threatened

CRM as predicted on MRI. The less the mesorectal

fat thickness, the less the depth of extramural

invasion it takes to infiltrate the CRM.

This study aimed to measure the amount of

mesorectal fat in the local population. The use and

limitation of T3 subclassification in the Chinese

population will be discussed.

Methods

A total of 25 consecutive staging MRIs done

for patients referred for rectal carcinoma

multidisciplinary meetings at a local regional hospital from

January to October 2012

were retrospectively reviewed by two radiologists

with special interest in abdominal imaging.

All MRI examinations were acquired with

1.5T MRIs in two local centres using Siemens

Magnetom Avanto (Erlangen, Germany) MRI

machines. Measurements were made with mutual

agreement between the two reviewing radiologists.

The thickness of mesorectal fat was defined as the

distance from the serosa to the mesorectal fascia in

the axial plane. The distance in mm was obtained

in the true axial plane at levels of 5 cm, 7.5 cm, and

10 cm from the anal verge. Measurements were

performed primarily on T2 sequence, supplemented

by T1 sequence if the acquired T2 images were

unsatisfactory. As this study involved two hospitals,

the scanning parameter was not identical. However,

such difference was not assumed to attribute to error of any

source in terms of calibre measurement.

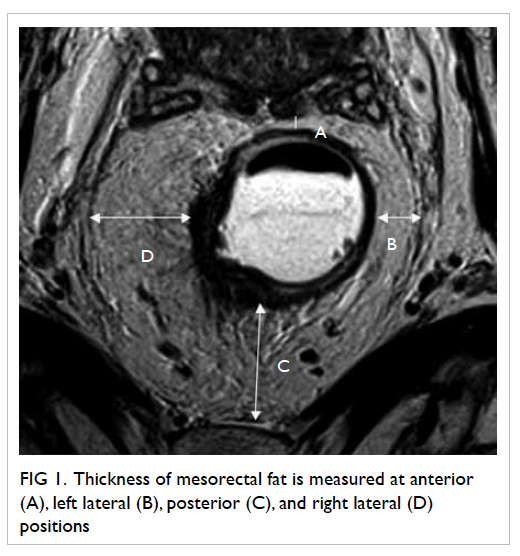

Four readings were obtained at each level,

namely, anterior, left lateral, posterior, and right

lateral positions (Fig

1).

Figure 1. Thickness of mesorectal fat is measured at anterior (A), left lateral (B), posterior (C) and right lateral (D) positions

Patients with bulky primary or secondary

pelvic

tumours (>3 cm in diameter) were excluded from

the study, as these might potentially cause significant

distortion of the anatomy and configuration of the

mesorectum.

Statistical analysis was performed with the

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Windows

version 15.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US). One-sample

Student’s t test was performed for analysis of

mean thickness.

Results

A total of 25 patients (16 males, 9

females) with a median age of 69 (range, 38-84) years were

included

in the study. The rectosigmoid junctions were

reached at the level of 10 cm above the anal verge

for four patients and were, thus, excluded from

calculation for the respective level.

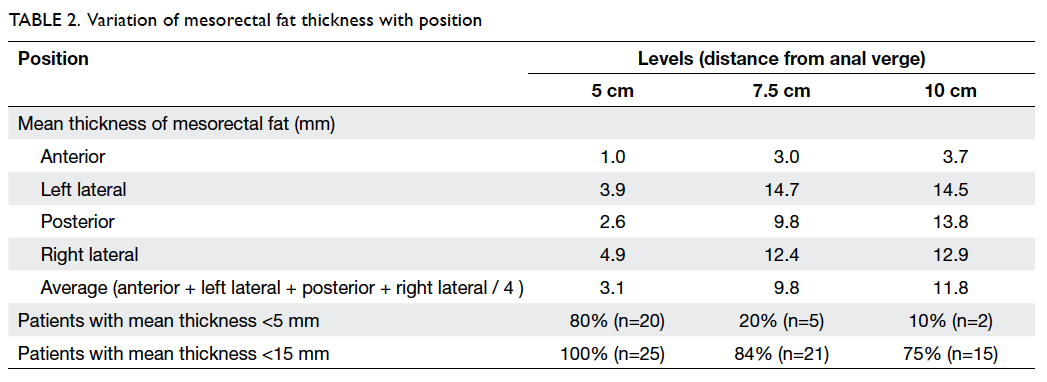

Mean thicknesses of mesorectal fat at 5 cm,

7.5 cm,

and 10 cm from the anal verge were 3.1 (standard

deviation [SD]=3.0) mm, 9.8 (SD=5.3) mm, and

11.8 (SD=4.2) mm, respectively. Details of the

mean mesorectal fat thickness are shown in Table

2. In brief, the proportions of patients with mean

mesorectal fat thickness of <15 mm were

100%, 84%, and 75% at 5 cm, 7.5 cm, and 10 cm from

the anal verge, respectively.

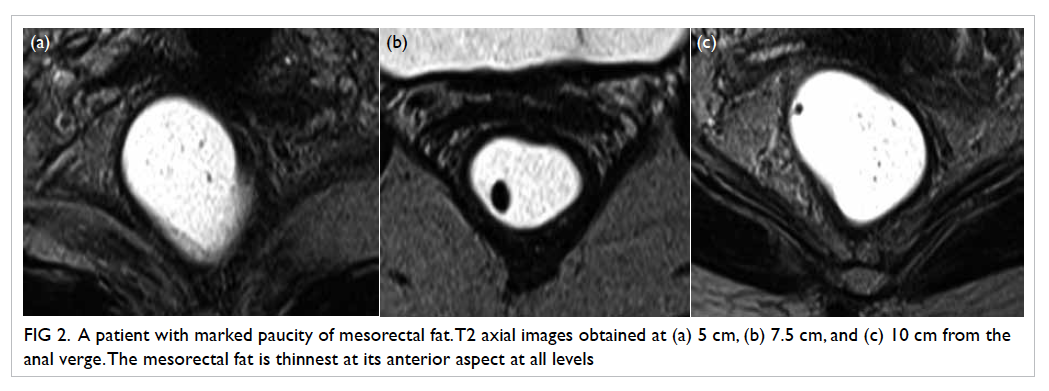

The mesorectal fat was noted to be the

least

thick in the anterior position for all three arbitrary

levels (Table

2; Fig

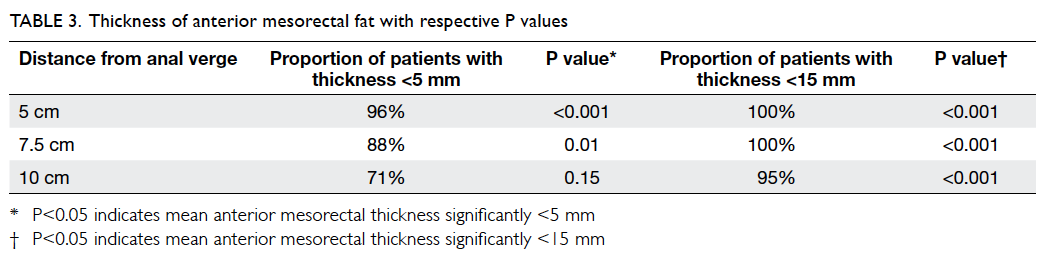

2). At 5 cm and 7.5 cm from the anal verge, proportions of

patients with mesorectal

fat thickness of <5 mm were 96% and 88%,

respectively. The figure reached up to 100% if 15 mm

was taken as the cutoff level. At 10 cm from the

anal verge, 95% of patients showed mesorectal fat

thickness of <15 mm. t Tests showed that the

anterior mesorectal fat thickness was significantly

<15 mm at all three levels (P<0.001) and

<5 mm at both 5 cm (P<0.001) and 7.5 cm

(P=0.01) from the anal verge (Table

3).

Figure 2. A patient with marked paucity of mesorectal fat. T2 axial images obtained at (a) 5 cm, (b) 7.5 cm, and (c) 10 cm from the anal verge. The mesorectal fat is thinnest at its anterior aspect at all levels

There was a tendency for the lateral

aspects

to be more spacious than the anterior and posterior

aspects, and for the left side to be larger than the right

side. However, these findings were not statistically

significant.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the

first

Chinese study and the first study in Asian subjects

on mesorectal fat thickness. The majority of

published literature on MRI staging of carcinoma

of rectum are based, predominantly, on data from

western/Caucasian populations. It has been well

known that variations in body build, lean mass, and

fat composition do occur across ethnic groups.10

Chinese or Asian patients have a smaller body build.

Whether the amount of fat in the mesorectum is the

same in Chinese and Caucasian population remains

largely unknown.

In recent decades, total mesorectal

excision

has revolutionised rectal cancer surgery.11

Patients

with relatively early tumours (ie T3b or below,

lymph node–negative) are usually streamlined to

total mesorectal excision without preoperative

neoadjuvant therapy. The rationale behind this is

that early, mid- and low-rectal tumours with their

whole lymphatic drainage are contained within the

mesorectal fascia. Total mesorectal excision allows

en-bloc removal of the tumour together with its

intact mesorectal fascia. A low local recurrence rate

of only 4% has been reported.12

An involved CRM is an independent disease

prognostic indicator.13 It

is defined pathologically as

identifying tumour cells within 1 mm of the surgically

created margin. Beets-Tan et al14

postulated that, on

MRI, a distance of 6 mm from the outer edge of the

tumour to the mesorectal fascia predicted a tumour

distance of 2 mm on histology with 97% confidence,

and a distance of 5 mm could predict a crucial

distance of 1 mm on histology with high confidence.

A study using 1 mm as cutoff showed data with

satisfactory accuracy despite a lower sensitivity.15

For practical purposes, we have adopted a cutoff of

5 mm as the predictor of clear CRM.

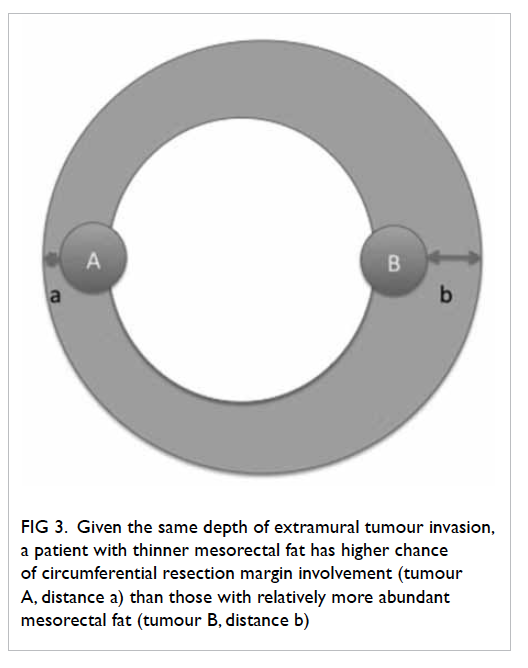

Given a certain depth of tumour invasion,

CRM is more likely to be threatened for patients with

thinner mesorectal fat (Fig

3). The mean thickness of

mesorectal fat is <15 mm for the majority of patients at all

arbitrarily measured levels. Taking

into account the margin of 5 mm on MRI, a tumour

invading 10 mm beyond the serosa on MRI fulfils

the criteria for threatened CRM in the majority of

patients. Whether Chinese patients present with

later-stage disease or have worse disease prognosis is

largely unknown. However, caution has to be taken

that T3a/b disease in Chinese populations does not

equal, or even imply, early-stage disease.

Figure 3. Given the same depth of extramural tumour invasion, a patient with thinner mesorectal fat has higher chance of circumferential resection margin involvement (tumour A, distance a) than those with relatively more abundant mesorectal fat (tumour B, distance b)

The position of the tumour may also affect

the

chance of mesorectal fat infiltration. The anterior

aspect of the mesorectal fat was found to be thinnest

at all three arbitrary levels. This is in agreement with

studies in European populations.16

The postulated

reason is that the anterior mesorectal fat tends to

be compressed by anterior pelvic organs such as the

uterus and prostate when one lies in supine position,

the position where MRI is conventionally acquired.

As a result, anterior tumour tends to threaten the

CRM with relatively shallow subserosal penetration.

The mesorectal fat is thinner inferiorly as

it

approaches the anal verge. Low rectal cancer (<5 cm

from the anal verge) has overall worse prognosis.

Higher local recurrence rate with higher chances

of CRM involvement has been reported.17

This may

be partly explained by the fact that the amount of

mesorectal fat is thinner in low rectum. Low rectal

tumours also deserve special surgical attention.18

One major weakness of this study was that

body mass index (BMI) was not taken into account.

However, a study in the UK19

has shown that BMI does not affect the thickness or volume of

mesorectal

fat. However, the measurement method employed

in that study was different from that in our study,

rendering direct comparison difficult. Whether

the paucity of mesorectal fat in Chinese patients is

due to body build or genetic factors is unknown.

Further multicentre studies with collection of BMI

data and ethnic information and using standardised

measurement methods are needed for better

comparison.

Conclusion

Thickness of mesorectal fat is shown to be

<15 mm in the majority of patients in most positions

and at most levels. It was <5 mm for low rectal

position. T3a/b tumours may paradoxically infiltrate

the mesorectal fascia in the study population. In

staging of Chinese rectal cancer patients, T3a/b

tumours may threaten the CRM in the majority of

locations and patients. Thus, the status of T3a/b

alone should not be taken as an indicator of early-stage

disease.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dr John KW

Chan

and St Paul’s Hospital for courtesy of MRI images.

References

1. Sagar PM, Pemberton JH. Surgical

management of locally

recurrent rectal cancer. Br J Surg 1996;83:293-304. CrossRef

2. Beets-Tan RG, Beets GL. Rectal

cancer: review with

emphasis on MR imaging. Radiology 2004;232:335-46. CrossRef

3. Bipat S, Glas AS, Slors FJ,

Zwinderman AH, Bossuyt PM,

Stoker J. Rectal cancer: local staging and assessment of

lymph node involvement with endoluminal US, CT, and

MR imaging—meta-analysis. Radiology 2004;232:773-83. CrossRef

4. Pedersen BG, Moran B, Brown G,

Blomqvist L, Fenger-Grøn M, Laurberg S. Reproducibility of depth

of

extramural tumor spread and distance to circumferential

resection margin at rectal MRI: enhancement of clinical

guidelines for neoadjuvant therapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol

2011;197:1360-6. CrossRef

5. van Gijn W, Marijnen CA,

Nagtegaal ID, et al. Preoperative

radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision

for resectable rectal cancer: 12-year follow-up of the

multicentre, randomised controlled TME trial. Lancet

Oncol 2011;12:575-82. CrossRef

6. Lahaye MJ, Engelen SM, Nelemans

PJ, et al. Imaging for predicting the risk factors—the

circumferential resection

margin and nodal disease—of local recurrence in rectal

cancer: a meta-analysis. Semin Ultrasound CT MR

2005;26:259-68. CrossRef

7. Shin R, Jeong SY, Yoo HY, et al.

Depth of mesorectal

extension has prognostic significance in patients with T3

rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2012;55:1220-8. CrossRef

8. Glimelius B, Tiret E, Cervantes

A, Arnold D; ESMO

Guidelines Working Group. Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical

Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up.

Ann Oncol 2013;24 Suppl 6:vi81-8. CrossRef

9. MERCURY Study Group. Extramural

depth of tumor

invasion at thin-section MR in patients with rectal cancer:

results of the MERCURY study. Radiology 2007;243:132-9. CrossRef

10. Lear SA, Kohli S, Bondy GP,

Tchernof A, Sniderman

AD. Ethnic variation in fat and lean body mass and the

association with insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol

Metab 2009;94:4696-702. CrossRef

11. Heald RJ, Ryall RD. Recurrence

and survival after

total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lancet

1986;327:1479-82. CrossRef

12. Heald RJ, Moran BJ, Ryall RD,

Sexton R, MacFarlane

JK. Rectal cancer: the Basingstoke experience of total

mesorectal excision, 1978-1997. Arch Surg 1998;133:894-9. CrossRef

13. Bernstein TE, Endreseth BH,

Romundstad P, Wibe A;

Norwegian Colorectal Cancer Group. Circumferential

resection margin as a prognostic factor in rectal cancer. Br

J Surg 2009;96:1348-57. CrossRef

14. Beets-Tan RG, Beets GL,

Vliegen RF, et al. Accuracy of

magnetic resonance imaging in prediction of tumour-free

resection margin in rectal cancer surgery. Lancet

2001;357:497-504. CrossRef

15. MERCURY Study Group.

Diagnostic accuracy of

preoperative magnetic resonance imaging in predicting

curative resection of rectal cancer: prospective

observational study. BMJ 2006;333:779. CrossRef

16. Torkzad MR, Blomqvist L. The

mesorectum: morphometric

assessment with magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Radiol

2005;15:1184-91. CrossRef

17. Nagtegaal ID, van de Velde CJ,

Marijnen CA, van Krieken

JH, Quirke P; Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group; Pathology

Review Committee. Low rectal cancer: a call for a change

of approach in abdominoperineal resection. J Clin Oncol

2005;23:9257-64. CrossRef

18. Salerno G, Daniels IR, Brown

G. Magnetic resonance

imaging of the low rectum: defining the radiological

anatomy. Colorectal Dis 2006;8 Suppl 3:10-3. CrossRef

19. Allen SD, Gada V, Blunt DM.

Variation of mesorectal

volume with abdominal fat volume in patients with rectal

carcinoma: assessment with MRI. Br J Radiol 2007;80:242-7. CrossRef