DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134097

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Recipes and general herbal formulae in books: causes of herbal poisoning

YK Chong, MB, BS1; CK Ching, FRCPA, FHKAM (Pathology)1; SW Ng, MPhil1; ML Tse, FHKCEM, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)2; Tony WL Mak, FRCPath, FHKAM (Pathology)1

1 Hospital Authority Toxicology Reference Laboratory, Princess Margaret

Hospital, Laichikok, Hong Kong

2 Hong Kong Poison Information Centre, United Christian Hospital, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Tony WL Mak (makwl@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Traditional Chinese medicine is commonly used

locally, not only for disease treatment but also for

improving health. Many people prepare soups

containing herbs or herbal decoctions according

to recipes and general herbal formulae commonly

available in books, magazines, and newspapers

without consulting Chinese medicine practitioners.

However, such practice can be dangerous. We report

five cases of poisoning from 2007 to 2012 occurring

as a result of inappropriate use of herbs in recipes

or general herbal formulae acquired from books.

Aconite poisoning due to overdose or inadequate

processing accounted for three cases. The other two

cases involved the use of herbs containing Strychnos

alkaloids and Sophora alkaloids. These cases

demonstrated that inappropriate use of Chinese medicine can result in major morbidity, and herbal

formulae and recipes containing herbs available in

general publications are not always safe.

Introduction

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is generally

regarded by the public as benign and non-toxic

compared with western medications. However, this

belief may be untrue. Indeed, herbal poisoning cases

are not uncommon locally.1 2 Traditional Chinese

medicine is often considered by the Chinese as part of

a ‘healthy’ diet to improve the general health. Instead

of consulting Chinese medicine practitioners, many

people prepare herbal soups or decoctions according

to recipes and herbal formulae commonly available

in books, magazines, and newspapers. However, the

risk of such practice may be under-recognised.

From 2007 to 2012, the Hospital Authority

Toxicology Reference Laboratory confirmed five

cases of herbal poisoning related to the use of soups

or herbal decoctions prepared according to recipes

or general herbal formulae acquired from books. We

report these cases to highlight the potential danger

associated with such practice.

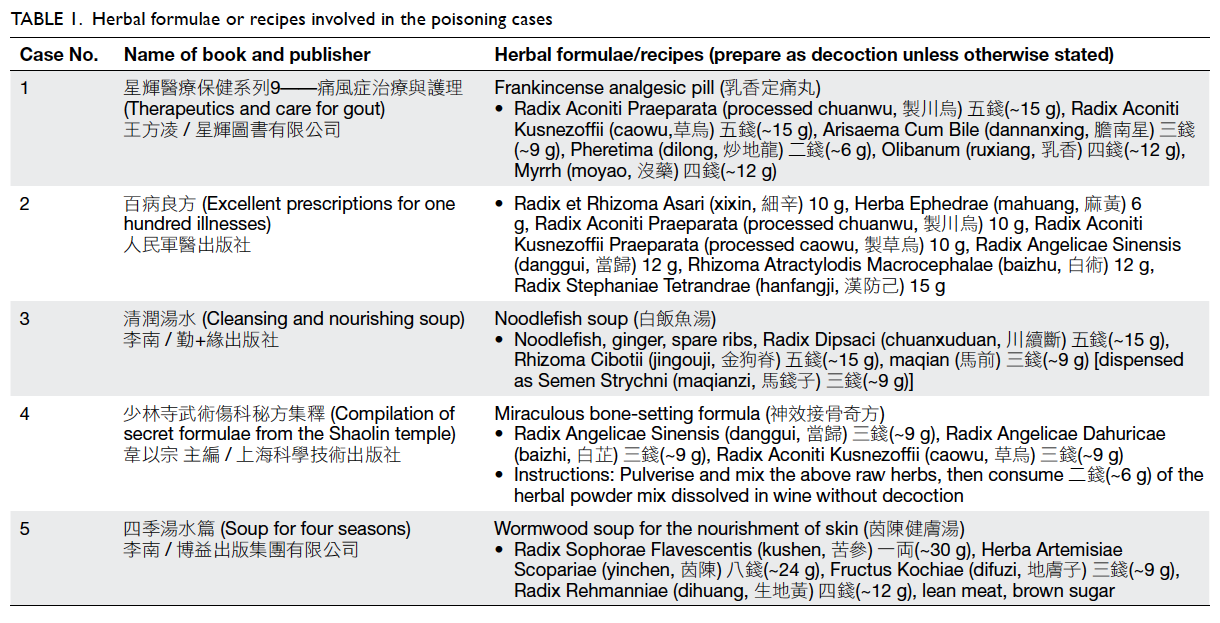

Case reports

Case 1

A 77-year-old man with a history of chronic

obstructive airway disease and gouty arthritis

presented in April 2008 with shortness of breath

and generalised numbness. His symptoms started

1 hour after consumption of a herbal decoction prepared from a formula “Frankincense analgesic

pill” available in the book “Therapeutics and care

for gout”. He developed atrial fibrillation and

hypotension, and later deteriorated into respiratory

failure necessitating intubation and ventilation with

intensive care. He also developed multiple episodes

of ventricular fibrillation. His condition improved

after supportive treatment, and he was discharged 5

days after admission.

Liquid chromatography–tandem mass

spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) of herbal remnants

and urine specimens showed presence of

Aconitum alkaloids (yunaconitine, hypoaconitine,

mesaconitine, aconitine). Thus, the patient was

diagnosed with severe aconite poisoning. The herbal

formula was found to contain two aconite herbs,

processed chuanwu 15 g and caowu 15 g, among

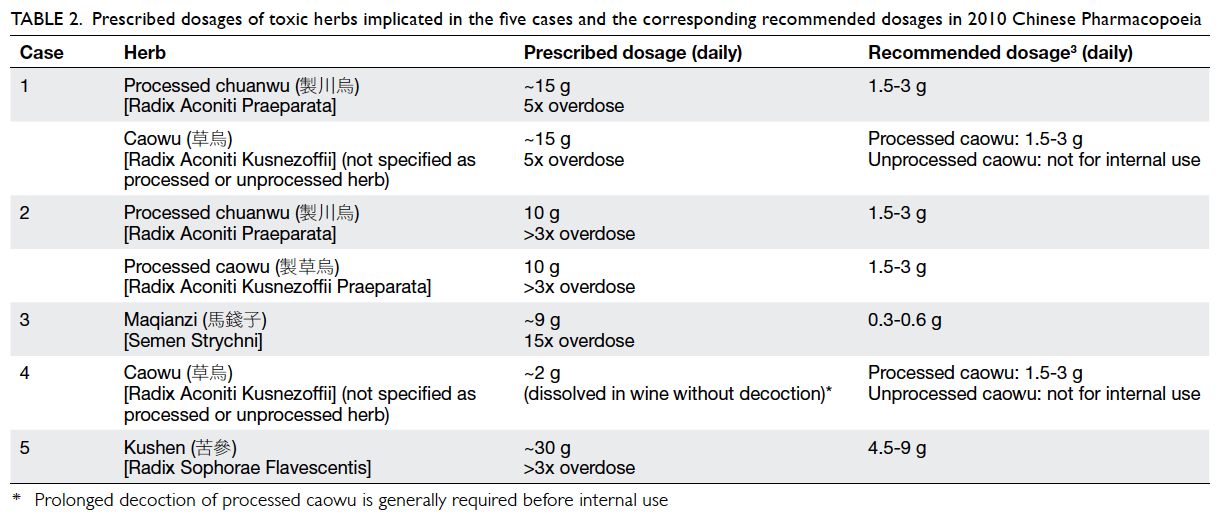

other herbs (Table 1). The dosages were 5 times

the upper limit of recommended dosages in the 2010

Chinese Pharmacopoeia,3 and worse still, it was not

mentioned whether caowu in the formula had been

processed (Table 2).

Table 2. Prescribed dosages of toxic herbs implicated in the five cases and the corresponding recommended dosages in 2010 Chinese Pharmacopoeia

Case 2

A 52-year-old man presented in March 2009 with

generalised numbness, weakness, and abdominal

pain after taking a herbal decoction prepared from

a formula in the book “Excellent prescriptions for

one hundred illnesses”. He complained of palpitation and was found to have ventricular bigeminy. He

developed shock shortly afterwards requiring

dopamine infusion. His condition improved with

supportive management and he was discharged after

3 days.

There were seven herbs in the formula, including

processed chuanwu 10 g and processed caowu

10 g (Table 1). Aconitum alkaloids (yunaconitine,

aconitine, deoxyaconitine, hypaconitine, and

mesaconitine) and their hydrolysed products were

detected in both urine and herbal remnant samples

by LC-MS/MS and gas chromatography–mass

spectrometry (GC-MS). The patient was diagnosed

with severe aconite poisoning. Contributory factors

included a three-fold overdose (Tables 1 and 2), and

the concomitant use of two aconite herbs.

Case 3

A 54-year-old woman presented in November

2007 with a 2-day history of leg cramps, dizziness,

sweating, and vomiting. She reported taking

“Noodlefish soup” for her knee pain based on a

recipe in the book “Cleansing and nourishing soup”.

She had doubled the doses of all ingredients. She

experienced mild leg cramping 2 hours after taking

the soup. She reboiled the soup and consumed two

doses on the next day; then, she developed bilateral

lower limb cramping, tonic contractions, dizziness,

nausea, and vomiting. The patient was discharged

after 1 day of observation.

In the urine and herbal broth specimens,

Strychnos alkaloids (strychnine and brucine) were

detected by GC-MS and high-performance liquid

chromatography with diode-array detector.

The clinical diagnosis was strychnine

poisoning. The recipe contained 9 g of “maqian”

(Table 1), which is a synonym of maqianzi.4 The

dosage was 15 times higher than the recommended

dosage (Table 2).

Case 4

A 66-year-old man, with multiple medical diseases,

presented in February 2012 with hypotension and

dizziness 1 hour after consumption of herbal powder

prepared according to a “Miraculous bone-setting

formula” available in the book “Compilation of secret

formulae from the Shaolin temple”. He required fluid

resuscitation and was discharged on the second day.

In the herbal powder and urine sample, Aconitum alkaloids (aconitine, mesaconitine,

hypaconitine, yunaconitine, and deoxyaconitine)

and their hydrolysed products were detected

by GC-MS and LC-MS/MS. The diagnosis was

moderate aconite poisoning. The formula was found

to contain caowu and two other herbs (Tables 1

and 2). According to the instruction, the patient

pulverised and mixed 9 g of each of the three herbs,

and then consumed 6 g of the mixed herbal powder

dissolved in wine without decoction. Although the

actual dose of caowu consumed (2 g) was within the

recommended dosage, the herb was not intended for

internal use before prolonged decoction to hydrolyse

the toxic Aconitum alkaloids.

Case 5

A 40-year-old woman presented in October 2009

with nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and sweating 50

minutes after taking a bowl of soup prepared from

a recipe “Wormwood soup for the nourishment of

skin” in the book “Soup for four seasons” for her

skin rash. The ingredients of the recipe included

kushen 30 g among other ingredients (Table 1).

Neurological examination was unremarkable.

Clinically, matrine poisoning was suspected. After 4

hours of observation, her symptoms improved and

she was discharged.

The herbal remnant and urine samples were

found to contain Sophora alkaloids (matrine,

sophoridine, cytisine, and N-methylcytisine) by

GC-MS. The diagnosis was matrine poisoning.

The dosage of kushen in the recipe was 3 times

higher than the upper limit of recommended dosage

(Table 2).3

Discussion

In the Chinese culture, medicine and food are

considered one inseparable entity. It is very common

for the Chinese to add medicinal herbs in their soups

and dishes to achieve different goals—prevention of

illness, treatment of disease, and nourishment of the

body. Rather than consulting a Chinese medicine

practitioner, it is not uncommon for the Chinese

to prepare herbal decoctions or soups according

to formulae or recipes in newspapers, magazines,

or books. The risk associated with such practice,

however, may be under-recognised, as illustrated by

our cases.

Three of the five cases (cases 1, 2, and 4)

reported here were related to the use of aconite herbs,

which are frequently used in TCM for their anti-inflammatory

and analgesic properties. However,

aconite herbs are toxic with low therapeutic indices,

and processing and prolonged decoction are

necessary before internal use. Aconite poisoning,

characterised by limb and perioral numbness,

arrhythmia, hypotension and gastro-intestinal

disturbances, is the most common cause of severe

herbal poisoning locally.5 Our group has previously

summarised the clinical features of 52 cases of

aconite poisoning.1 Concerning the three cases

reported here, overdose was the cause of poisoning

in two cases, whereas the use of herbs without prior

decoction accounted for poisoning in the third one.

The issue of overdosing is further illustrated by

case 5, in which overdose of kushen (3 times the

recommended dose) was identified as the cause of

matrine poisoning. Sophora alkaloids, present in the

herb kushen, are known to cause dizziness, nausea, and vomiting.6 Neurological toxicity has also been

reported in severe cases.

The cause of strychnine poisoning in case 3

was traced to a typesetting error in the book; the

text said “maqian” instead of “mati” (water chestnut).

This was confirmed by crosschecking with the same

recipe in another book by the same author. Severe

strychnine poisoning can cause muscle twitching,

convulsions, rhabdomyolysis, and even death.

Despite doubling the dose of all herbs in the soup

with a 15 times higher dose of maqianzi, the clinical

toxicity of the patient was relatively mild. It could be

related to the fact that maqianzi was not pulverised

and remained intact after boiling.

The chain of events leading to clinical poisoning

in these cases reflects failure of multiple parties in

practising safe use of Chinese herbs. The authors

should exercise careful judgement in choosing safe

herbal formulae or recipes for inclusion in their

books, and there should be adequate quality control

by editors, especially to prevent typographic errors

that can lead to grave consequences. The general

public should be educated that Chinese medicine is

not always benign and safe, and consulting a Chinese

medicine practitioner before taking herbs is always

advisable.

The fact that gross overdoses of herbs were

being dispensed from the herbal shops also played

a role in these poisoning cases. Currently, except

the Schedule 1 Chinese medicines, no guideline

exists in Hong Kong on the maximum dosage of

a particular herb, including the toxic processed

aconite herbs, above which one cannot dispense.

Of note, the dosages dispensed in these cases were

well above the dosage recommended in the Chinese

Pharmacopoeia.7 We believe that the availability of

such guidelines will serve to improve the safety of

TCM.

Awareness and knowledge of common herbal poisoning among clinicians can allow correct

diagnosis and timely treatment of the poisoned

patients. Laboratory analyses of the herbal samples

and biological samples can help to confirm the

diagnosis.

Conclusion

The five unfortunate cases in this series illustrate that

inappropriate use of Chinese medicine can result

in significant morbidity. General herbal formulae

and recipes containing herbs are not always safe.

Enhancing the standards of these publications,

improving the practice of dispensing herbs, and

public education on the safe use of Chinese medicine

will, hopefully, prevent similar cases from happening

again.

References

1. Chen SP, Ng SW, Poon WT, et al. Aconite poisoning over

5 years: a case series in Hong Kong and lessons towards

herbal safety. Drug Saf 2012;35:575-87. CrossRef

2. Cheng KL, Chan YC, Mak TW, Tse ML, Lau FL. Chinese

herbal medicine–induced anticholinergic poisoning in

Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2013;19:38-41.

3. State Pharmacopoeia Commission. Chinese

Pharmacopoeia 2010. Volume I. Beijing, China: Chemical

Industry Press; 2010.

4. State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine; the

editorial committee of Chinese Materia Medica. China:

Shanghai Science and Technology Press; 1999.

5. Chan TY, Chan JC, Tomlinson B, Critchley JA. Chinese

herbal medicines revisited: a Hong Kong perspective.

Lancet 1993;342:1532-4. CrossRef

6. Drew AK, Bensoussan A, Whyte IM, Dawson AH, Zhu X,

Myers SP. Chinese herbal medicine toxicology database:

monograph on Radix Sophorae Flavescentis, “ku shen”. J

Toxicol Clin Toxicol 2002;40:173-6. CrossRef

7. Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government.

Chinese Medicine Ordinance (Cap 549, Laws of Hong

Kong); 2010.