DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134158

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

An uncommon cause of Cushing’s syndrome in a 70-year-old man

Kitty KT Cheung, MRCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1; WY So, FRCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1; Alice PS Kong, FRCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1; Ronald CW Ma, FRCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1; KF Lee, FRCSEd (Gen), FHKAM (Surgery)2; Francis CC Chow, FRCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1

1 Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

2 Department of Surgery, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Kitty KT Cheung (kittyktcheung@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Cushing’s syndrome due to exogenous steroids is

common, as about 1% of the general populations

use exogenous steroids for various indications.

Although endogenous Cushing’s syndrome due

to ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone from a

pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour is rare, a correct

and early diagnosis is important. The diagnosis

and management require high clinical acumen

and collaboration between different specialists.

We report a case of ectopic adrenocorticotropic

hormone Cushing’s syndrome due to pancreatic

neuroendocrine tumour with liver metastasis. Early

recognition by endocrinologists with timely surgical

resection followed by referral to oncologists led to a

favourable outcome for the patient up to 12 months after initial presentation.

Case report

In March 2013, a 70-year-old Chinese man presented

with polyuria and polydipsia was diagnosed to

have new-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus. He had

suboptimal glycaemic control, and received multiple

oral hypoglycaemic agents (OHAs). At the same

time, he was noted to have bilateral lower limb

pitting oedema and difficult to heal wounds over

feet, as well as persistent hypokalaemia for which he

was prescribed regular treatment with a potassium-sparing diuretic and oral potassium supplements.

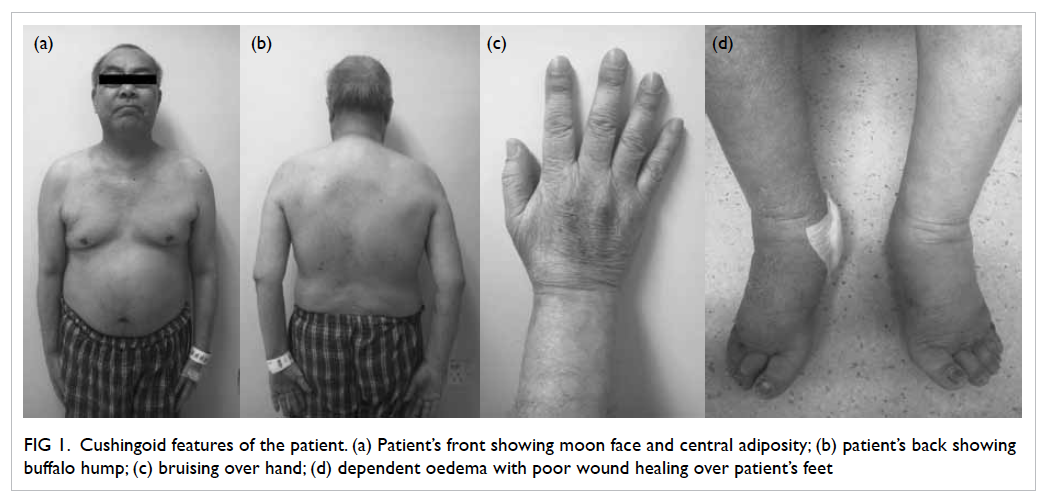

Symptoms and signs of Cushing’s syndrome (CS)

including easy bruising, proximal muscle weakness,

and central obesity were subsequently detected

(Fig 1). He denied any history of taking herbal

medicine or exogenous steroids. The overnight

1-mg dexamethasone screening test for CS yielded

a non-suppressible plasma cortisol level of 1308

(reference level [RL], <50) nmol/L. Paired 9am cortisol

and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels were 1220 nmol/L and 78 pmol/L (RL, <10.2

pmol/L), respectively. Two sets of values for 24-hour

urinary free cortisol excretion were strikingly

high at 2263 and 3601 nmol/day (reference range, 35-151 nmol/day). He also failed the confirmatory

low-dose dexamethasone suppression test with a

cortisol level of 997 nmol/L (RL, <50 nmol/L) after

2 days of dexamethasone loading. The peripheral

corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) stimulation

test later established the diagnosis of ectopic ACTH

CS, since both the ACTH and cortisol responses

were flat after CRH injection. Ketoconazole was

commenced at that juncture, which was 2 months

after the patient’s initial presentation.

Figure 1. Cushingoid features of the patient. (a) Patient’s front showing moon face and central adiposity; (b) patient’s back showing buffalo hump; (c) bruising over hand; (d) dependent oedema with poor wound healing over patient’s feet

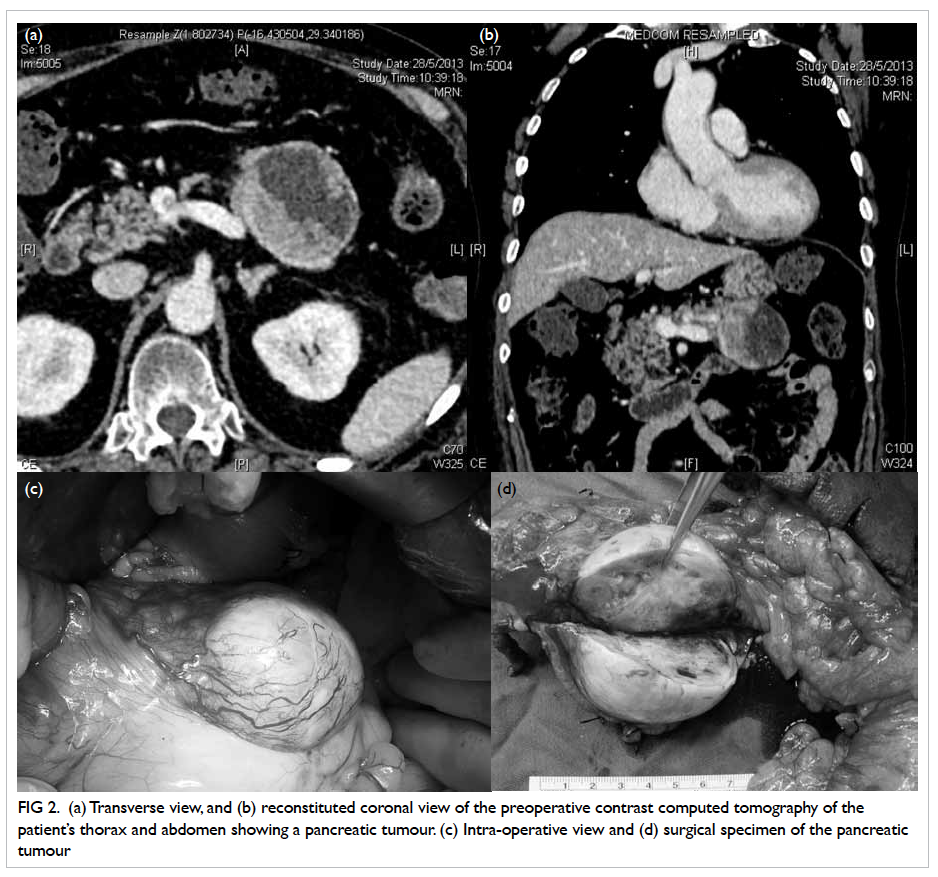

Contrast computed tomography (CT) of the

thorax and abdomen followed immediately, and

revealed a well-defined ovoid cystic area (6.3 x 4.8

x 4.9 cm) with an intralesional eccentric isodense

mildly enhanced mural nodule in the body of pancreas

that was consistent with pancreatic tumour, with

enlarged lymph nodes posterior to the body of the

organ (Figs 2a and 2b). Mild generalised osteoporosis

was also noted. Positron emission tomography (PET)

of the whole body 2 weeks later showed a mildly hypermetabolic heterogeneous lesion in the body of

the pancreas, compatible with the known pancreatic

tumour. Also, there were mildly hypermetabolic

lymph nodes in the peripancreatic region, possibly

due to early nodal involvement. The serum CA19.9 level (a tumour marker of pancreatic cancer) was

elevated (89 kIU/L; RL, <18 kIU/L).

Figure 2. (a) Transverse view, and (b) reconstituted coronal view of the preoperative contrast computed tomography of the patient’s thorax and abdomen showing a pancreatic tumour. (c) Intra-operative view and (d) surgical specimen of the pancreatic tumour

The patient was referred to surgeons 3

months after initial presentation, and offered distal

pancreatectomy with splenectomy (Figs 2c and 2d).

Intra-operatively, a solitary 2-mm nodule over the

undersurface of segment III of liver, not identified

in the preoperative CT, was found and histologically

confirmed to be metastatic neuroendocrine tumour

(NET). Intra-operative ultrasound did not reveal

any other liver lesions. There were no palpable

lesions over whole length of small bowel or colon

in the peritoneum or the omentum. Histology

of the resected pancreatic mass confirmed the

presence of malignant pancreatic NET (P-NET)

with extrapancreatic extension and lymphovascular

permeation. The tumour cells were diffusely positive

for CK19, synaptophysin, and chromogranin.

Staining for ACTH, gastrin, and pancreatic

polypeptidase were focally positive, but staining for

insulin, serotonin, somatostatin, and glucagon were

all negative. The proliferative pool as assessed by

Ki-67 was estimated to be approximately 15%.

Postoperatively, ketoconazole was stopped,

and the patient started taking replacement doses

of hydrocortisone. He was then referred to an

oncologist for further management in view of the

metastatic nature of his disease (stage IV P-NET due

to confirmed liver metastasis). One month after the

operation, the patient experienced marked alleviation

of his symptoms. He had no more oedema and the

OHA requirements were significantly reduced.

Discussion

Cushing’s syndrome due to exogenous steroids is

common, as about 1% of the general populations use

exogenous steroids for various indications.1 Ectopic

ACTH secretion accounts for approximately 10% to

20% of all cases of CS.2 The leading cause is small-cell

lung carcinoma, accounting for about 50% of

the cases. Other less common tumours reported

are pancreatic, bronchial, thymic, and thyroid

medullary carcinoma. Certainly, P-NETs are rare

and have an incidence of approximately 1/100 000

persons per year, and both genders appear equally

prone.3 Among the P-NETs, insulinoma, gastrinoma,

glucagonoma, somatostatinoma, and VIPoma have

all been reported. Other non-functioning islet

neoplasms and other hormone-secreting (eg ACTH)

tumours have also been published in case reports.4

Other than insulinoma, these P-NETs are generally

malignant. Those that are ACTH-producing

(account for approximately 1.2% of them) are particularly aggressive.4 Metastases, usually to the

liver, are often observed in early phase, even before

the presentation of CS.5 The 2- and 5-year survival

rates of patients with P-NETs are about 40% and

16%, respectively.6

Symptoms and signs from excess cortisol,

followed by biochemical evaluation and subsequent

imaging, as in our patient, are important in the timely

diagnosis of functioning P-NETs. In our patient,

both the screening and other confirmatory tests for

CS established the diagnosis. Non-suppressible/high

ACTH in the presence of high serum concentrations

and urinary secretion of cortisol, coupled with flat

ACTH and cortisol responses after provocative

peripheral CRH stimulation test, strongly suggested

the CS was due to an ectopic ACTH-secreting source

rather than the pituitary.

Other than the peripheral CRH stimulation test

which offers 86% sensitivity and 90% specificity for

pituitary CS,7 high-dose dexamethasone suppression

test (HDDST) and bilateral inferior petrosal sinus

(IPS) sampling for ACTH are two other options for

differentiating pituitary CS and ectopic ACTH CS.

A positive HDDST, characterised by suppression

of serum cortisol by ≥50% from baseline by 8 mg

of dexamethasone taken at 11 pm the night before,

offers 77% sensitivity and 60% specificity for CS.

The rationale for the use of HDDST is based on the

principle that pituitary tumours are only partially

autonomous, retaining feedback mechanism at a

higher set point than normal. Therefore, when enough

dexamethasone is administered, ACTH and cortisol

secretion can be suppressed. While for ectopic

ACTH tumours, which are usually autonomous,

production of hormones cannot be suppressed with

dexamethasone. However, some benign ectopic

tumours may be suppressible, while pituitary

macroadenomas are often non-suppressible.7 Whilst

IPS sampling is invasive, it is the most direct way

to examine whether the pituitary is the source of

excess ACTH. An IPS/periphery ACTH ratio of >2.0

correctly identifies CS with 95% sensitivity and 100%

specificity. The sensitivity is further improved to

100% when CRH is administered using the cut-off of

post-CRH IPS/periphery ratio of >3.0.8

In our case, immediate search for the ACTH-secreting

source using CT and PET identified

the pancreatic tumour promptly. Other imaging

modalities commonly used in localising NETs

include magnetic resonance imaging, endoscopic

ultrasound, and somatostatin receptor scintigraphy.

The source of ACTH in 30% to 50% of patients

with ACTH-dependent CS is not localised by the

conventional imaging modalities listed above.9

Newer imaging techniques such as fluorine-labelled

dihydroxyphenylalanine (18F-DOPA) PET/CT are

now being used to localise occult sources, although

the usefulness of some of them remains controversial. In a series of 17 patients, no advantage was seen

with tumour localisation using (18F-DOPA) PET/CT

when compared with conventional imaging, while

another study reported 100% localisation of ectopic

ACTH-secreting NETs using (18F-DOPA) PET/CT

in three patients.9 10

Treatments for P-NETs include surgery,

chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and interventional

radiology techniques such as hepatic artery chemoembolisation.

Surgery is the first-line option for

resectable tumours and is also used for debulking

metastatic tumours. Total hepatectomy with living

donor transplantation has also been attempted

for treating metastatic tumours.11 Somatostatin

and its analogues have both antisecretory and

antiproliferative effects.12 Although P-NETs are

relatively radioresistant, recently developed peptide

receptor radiotherapy employing radionuclide-targeted

somatostatin receptor agonists for internal

cytotoxic radiotherapy in somatostatin receptor-expressing

NETs seem promising.12 Systemic

therapies for unresectable tumours include sunitinib

malate, a potent tyrosine kinase inhibitor with

antiangiogenic effects, and everolimus, an inhibitor

of mammalian target of rapamycin.12 13 After surgical

resection of malignant P-NETs, Ki-67 >5% of tumour

cells is a predictor of recurrence.5 Since our patient

had a Ki-67 of approximately 15%, oncological

treatment will be needed, hence, the referral.

In conclusion, our patient with an ectopic

ACTH-secreting P-NET presented with diabetes and

hypertension, both of which are common chronic

diseases worldwide. Due to the aggressive nature of

this type of tumour and its histological findings, this

patient will likely require further adjuvant treatments

in the future. Ectopic ACTH CS can occur due to

a wide spectrum of causes, and a combination of

relevant biochemical tests and imaging are needed

to establish the correct diagnosis. Timely referral to

surgeons and/or oncologists is necessary. Symptoms

of hormone excess are often the first hint suggesting

the diagnosis of functioning P-NETs. Almost all

P-NETs, except insulinoma, carry a high malignant

potential. Expeditious and meticulous management

involving collaboration between endocrinologists,

surgeons, pathologists, and oncologists can be

expected to provide the best outcomes for patients suffering from this rare disease.

References

1. Prague JK, May S, Whitelaw BC. Cushing’s syndrome. BMJ

2013;346:f945. CrossRef

2. Wajchenberg BL, Mendonca BB, Liberman B, et al. Ectopic

adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome. Endocr Rev

1994;15:752-87. CrossRef

3. Eriksson B, Oberg K. Neuroendocrine tumours of the

pancreas. Br J Surg 2000;87:129-31. CrossRef

4. Ito T, Tanaka M, Sasano H, et al. Preliminary results

of a Japanese nationwide survey of neuroendocrine

gastrointestinal tumors. J Gastroenterol 2007;42:497-500. CrossRef

5. Doppman JL, Nieman LK, Cutler GB Jr, et al.

Adrenocorticotropic hormone–secreting islet cell tumors:

are they always malignant? Radiology 1994;190:59-64. CrossRef

6. Clark ES, Carney JA. Pancreatic islet cell tumor associated

with Cushing’s syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 1984;8:917-24. CrossRef

7. Reimondo G, Paccotti P, Minetto M, et al. The

corticotrophin-releasing hormone test is the most reliable

noninvasive method to differentiate pituitary from ectopic

ACTH secretion in Cushing’s syndrome. Clin Endocrinol

(Oxf) 2003;58:718-24. CrossRef

8. Invitti C, Pecori Giraldi F, de Martin M, Cavagnini F.

Diagnosis and management of Cushing’s syndrome: results

of an Italian multicentre study. Study Group of the Italian

Society of Endocrinology on the Pathophysiology of the

Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis. J Clin Endocrinol

Metab 1999;84:440-8. CrossRef

9. Pacak K, Ilias I, Chen CC, Carrasquillo JA, Whatley

M, Nieman LK. The role of [(18)F]fluorodeoxyglucose

positron emission tomography and [(111)In]-diethylenetriaminepentaacetate-D-Phe-pentetreotide

scintigraphy in the localization of ectopic

adrenocorticotropin-secreting tumors causing Cushing’s

syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:2214-21. CrossRef

10. Kumar J, Spring M, Carroll PV, Barrington SF, Powrie JK.

18Flurodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in the

localization of ectopic ACTH-secreting neuroendocrine

tumours. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2006;64:371-4.

11. Blonski WC, Reddy KR, Shaked A, Siegelman E, Metz

DC. Liver transplantation for metastatic neuroendocrine

tumor: a case report and review of the literature. World J

Gastroenterol 2005;11:7676-83.

12. Wiedenmann B, Pavel M, Kos-Kudla B. From targets to

treatments: a review of molecular targets in pancreatic

neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology

2011;94:177-90. CrossRef

13. Hörsch D, Grabowski P, Schneider CP, et al. Current

treatment options for neuroendocrine tumors. Drugs

Today (Barc) 2011;47:773-86.