Hong Kong Med J 2014 Aug;20(4):297–303 | Epub 23 May 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134074

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Factors associated with intimate partner

violence against women in a mega city of South-Asia: multi-centre

cross-sectional study

Niloufer S Ali, MB, BS, FCPS1;

Farzana N Ali, MB, BS2; Ali K Khuwaja, MB, BS, FCPS3;

Kashmira Nanji, MSc, BScN1

1 Department of Family

Medicine, The Aga Khan University, Karachi

74800, Pakistan

2 Department of Family

Medicine and Community Health, University

Hospitals Case Medical Center, Ohio 44106, United States

3 Departments of Family

Medicine/Community Health Sciences, The Aga

Khan University, Karachi 74800, Pakistan

Corresponding author: Dr Kashmira Nanji (kashmira.nanji@aku.edu)

Abstract

Objectives: To assess

the proportion of women

subjected to intimate partner violence and the

associated factors, and to identify the attitudes

of women towards the use of violence by their

husbands.

Design: Cross-sectional

study.

Setting: Family practice

clinics at a teaching hospital

in Karachi, Pakistan.

Participants: A total of

520 women aged between

16 and 60 years were consecutively approached

to participate in the study and interviewed by

trained data collectors. Overall, 401 completed

questionnaires were available for analysis.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to

identify the association of various factors of interest.

Results: In all, 35% of

the women reported being

physically abused by their husbands in the last

12 months. Multivariate analysis showed that

experiences of violence were independently

associated with women’s illiteracy (adjusted odds

ratio=5.9; 95% confidence interval, 1.8-19.6),

husband’s illiteracy (3.9; 1.4-10.7), smoking habit of husbands

(3.3; 1.9-5.8), and substance use (3.1; 1.7-5.7).

Conclusion: It is

imperative that intimate partner

violence be considered a major public health

concern. It can be prevented through comprehensive,

multifaceted, and integrated approaches. The role

of education is greatly emphasised in changing the

perspectives of individuals and societies against

intimate partner violence.

New knowledge added by this

study

- This study shows that women’s literacy can play an important role in changing the perspectives of individuals and societies towards violence against women.

- Substance abuse including smoking and alcohol consumption may directly be responsible for intimate partner violence against women in Pakistan.

- The growing understanding of the impact of violence needs to be translated into primary, secondary, and tertiary level prevention, including both services that respond to the needs of women living with or who have experienced violence, and interventions to prevent violence.

- There is a need for intervention programmes in all societies and cultures for both men and women to highlight this imperative issue.

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) against

women is

a global human rights and public health problem.

Addressing violence against women (VAW) is central

to the achievement of Millennium Development

Goal (MDG) 3 on women’s empowerment and

gender equality, as well as MDGs 4, 5, and 6.1 Intimate

partner violence is defined as “the range of sexually,

psychologically and physically coercive acts used

against adult and adolescent women by current or

former male intimate partners”.2

The two terms, VAW and IPV, are used

interchangeably with gender-based violence. It

is reported that violence imposed by husbands is

the most common form of VAW.3

Data from the

World Bank suggest that women aged 15 to 44

years are at greater risk from rape and domestic

violence than from cancer, motor accidents, war,

and malaria.3 There is

enormous body of evidence

to suggest that such acts of violence adversely affect

the overall wellbeing of women and are associated

with psychiatric morbidities like anxiety, depression, addictive

behaviour, etc, and physical injuries,

sexually transmitted infections, poor reproductive

health outcomes, and even death.4

5 6 7 The

impact may

also span to affect the mental and physical health of

children, who may get “caught in the cross fire” and

are directly injured or may get less directly affected

as a consequence of abusive relationship between

parents.8 9

Violence against intimate partners occurs

in all

countries, all cultures, and at every level of society

without exception, although some populations (for

example, low-income groups) are at greater risk of

violence by intimate partners than others.10 In 48

population-based surveys from around the world,

10% to 69% of women reported being physically

assaulted by an intimate male partner at some point

in their lives.3 The World

Health Organization

(WHO) multi-country study on women’s health and

domestic violence documented lifetime prevalence

of physical and/or sexual partner violence among

ever-partnered women in the 15 sites surveyed

ranging from as low as 15% in an Ethiopian province

to as high as 71% in Japan.11

The burden of IPV is particularly alarming

in

developing countries as women are vulnerable to

many forms of violence and IPV represents the most

common form.

The widespread nature of the issue is

further evidenced by the findings of more recent

studies from countries with varied economic

and developmental strata. About 15% of women

visiting the family practitioners in Toronto, Canada, admitted

being victims of IPV.12

Another study

from a developing country reported the prevalence

of male partner–perpetrated violence to be around

7%.13 Although a true

comparison is difficult to

make due to methodological differences between

studies, in general, a higher burden of the problem

is observed in developing countries, including those

from South Asia. Around one third to one half of the

female participants in different studies from India

accept IPV victimisation.13

14 According to the recent

Bangladesh Demographic Health Survey, almost

half of married Bangladeshi mothers (42.4%) with

children aged 5 years and younger experienced IPV

from their husbands.14

Similarly, in Pakistan, nearly

one third to one half of the women stated that they

are victims of IPV.15 16

Although the prevalence of IPV varies

across

countries, the factors associated with an increased

risk of IPV are similar. These may include substance/alcohol use, young age, and attitudes supportive of

wife beating. However, higher education status, high

socio-economic status, and formal marriage offer

protection against IPV.11

17 18

Limited data are available from Pakistan on

VAW. The topic remains largely inadequately studied

despite its far-reaching adverse consequences.

Moreover, most of the published studies have

been conducted in the same communities or

in communities with similar socio-economic

backgrounds, skewing the approximate magnitude

of the problem to extremes and hampering the

analysis of important demographic factors that may

be associated with IPV against women. The aim of

this study was therefore to estimate the proportion of

women subjected to IPV in Pakistan and to examine

whether demographic factors such as education

status of both wife and husband and husband’s

involvement in substance abuse were associated

with IPV. We conducted this study among women

from diverse socio-economic backgrounds to assess

the proportion of women subjected to IPV and the

associated factors. We also aimed to determine the

attitudes of participants towards the use of violence

by husbands.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in

four

family practice clinics situated in various localities

of Karachi, the largest city and economic hub of

Pakistan. Karachi is one of the largest metropolitan

cities of the world where over 16 million people

reside; it is also called mini-Pakistan as its residents

represent all the ethnicities, provinces/states, and

socio-economic classes. All these clinics are affiliated

with a private tertiary care teaching hospital. A total

of eight family practice clinics are associated with the

teaching hospital and these clinics were included as

they provide health services to people from different

socio-economic strata (lower, middle, and upper). All

participants were assured of complete confidentiality

of the information collected. After obtaining consent

to participate in the study, currently married women

(aged 16-60 years) were interviewed consecutively

by four female medical students (each in a clinic)

who had received prior training for this task. The

data were collected simultaneously in all the clinics

from July 2012 to November 2012. Sample size was

calculated with the help of WHO software for sample

size determination. As the prevalence of VAW ranges

between 30% and 50%,14 15 16 we used a prevalence of

50% for maximum variance with an error bound of

5%; this gave a sample size of 385. The sample size

was then inflated by 7% for non-respondents to give

a final sample size of approximately 412.

After extensive literature search and

consensus

by study investigators, a structured questionnaire

was developed and pre-tested. The questionnaire

was initially prepared in English, translated into

Urdu and then back-translated into English. The final

questionnaire was comprised of sections including

socio-demographic characteristics and questions

regarding the experience of physical/verbal abuse

inflicted ever (lifetime) by husband. In this study,

physical abuse was defined by any of the following

acts used against women: slapping or throwing

something at her that could hurt her; pushing or

shoving; hitting with fist or something else that

could hurt; kicking, dragging, or beating; choking

or burning on purpose; and threatening to use or

actually use a gun, knife, or weapon against her. The

questionnaire also included a section on the women’s

attitude towards use of violence by husbands against

wives. Questions were also included about other

variables of interest which included education

status of the woman and her husband, working

status of the woman and her husband, years since

marriage and total number of children, family

system in which the woman lives, and information

about smoking status and other addictive substances

used by the husband. The time required to complete

the questionnaire was about 25 to 30 minutes. Due

to the sensitivity of the issue, the interviews were

conducted with each participant in separate rooms

ensuring full privacy. The study was approved by the

Research Committee of the Department of Family

Medicine, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan,

and prior permission was sought by administration

of study clinics.

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the

Social

Sciences (Windows version 19; SPSS Inc, Chicago

[IL], US). The proportion of violence experienced

by women and other variables of interest were

calculated. Cross-tabulation and Chi squared test

were used to assess the association between the women’s perception

and their level of education.

The independent association of factors studied with

violence experienced by women was examined by

multivariate stepwise logistic regression analysis

to obtain odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence

intervals (CIs). Covariates such as education status

of participants, education status of husband, and

smoking and substance abuse by husband were

included in the multivariate model.

Results

A total of 550 women were approached, of

which 520

fulfilled the eligibility criteria. As there were 119 women who refused to participate or provided incomplete information in the questionnaire, the response rate was

77%. Finally, information from 401 participants

was included in the final analysis; for missing data,

we averaged estimates of the variables to give a

single mean estimate. The socio-demographic

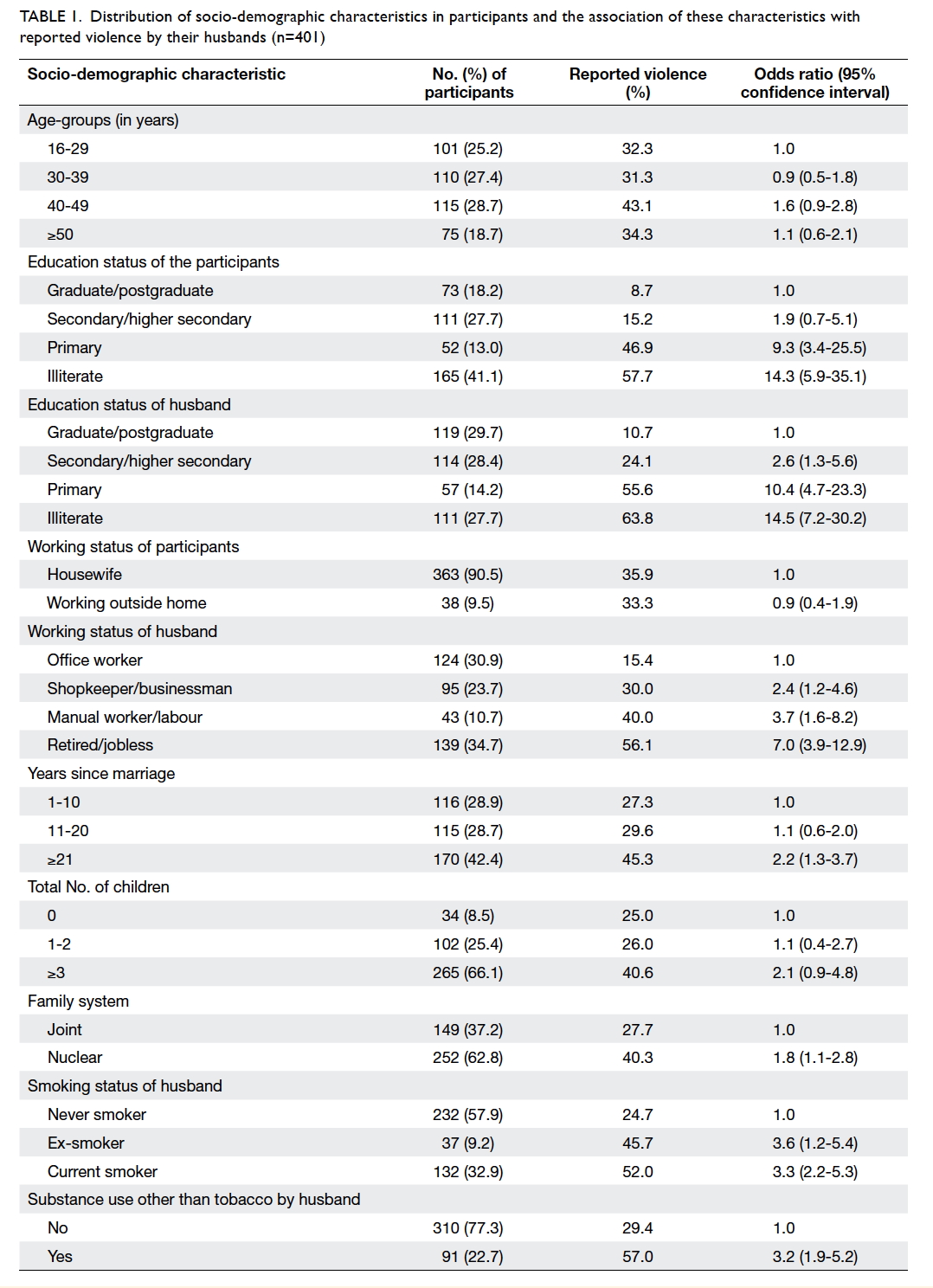

characteristics of the participants are summarised in

Table 1. Overall, 190 (47.4%) of the

participants were

aged 40 years and above, 165 (41.1%) had received

no education at all, and husbands of 111 (27.7%)

participants had received no schooling. A majority

(n=363; 90.5%) of respondents were housewives

while one third of the participants’ husbands were

not working (jobless or retired from work). Overall,

170 (42.4%) participants had been married for more

than 20 years, 265 (66.1%) had three or more children,

and 252 (62.8%) were living in nuclear (single)

families. Husbands of 132 (32.9%) participants were

current tobacco smokers and over one fifth of them

consumed addictive substances other than tobacco

smoking.

Table 1. Distribution of socio-demographic characteristics in participants and the association of these characteristics with reported violence by their husbands (n=401)

Overall, 140 (35%) participants reported

being ever physically/verbally violated by their

husbands in the last 12 months. The factors associated with IPV against

women on univariate analysis are summarised in

Table 1. These included illiteracy of women, living

in a nuclear family, and being married for more

than 20 years; factors related to the husband were

illiteracy, unemployment, smoking, and use of other

substances besides tobacco.

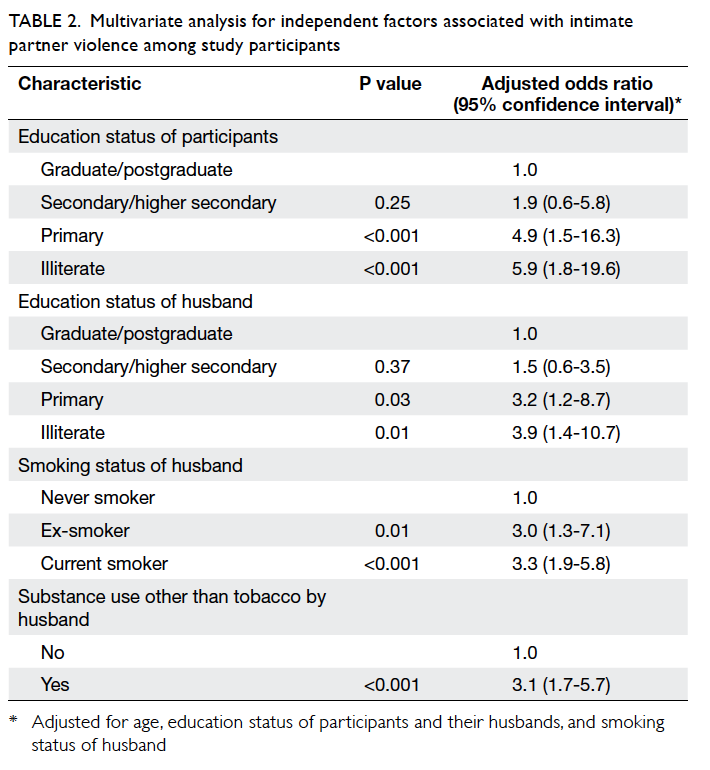

In the multivariate analysis (Table

2), four

factors were independently associated with IPV

against women. These were women’s illiteracy,

husband’s illiteracy, smoking habit of husband, and

use of substances other than tobacco by husband.

Women who were illiterate were 6 times more likely

to have been violated by their husbands versus

those who were literate (adjusted OR [AOR]=5.9;

95% CI, 1.8-19.6), while women whose husbands

were illiterate were 4 times more likely to have been

abused than those whose husbands were literate

(AOR=3.9; 95% CI, 1.4-10.7). Study participants

whose husbands smoked tobacco reported being

victims of violence by their husbands 3 times more

often than their counterparts (AOR=3.3; 95% CI,

1.9-5.8). Almost similar odds for IPV were observed in

participants whose husbands were addicted to

substances other than tobacco (AOR=3.1; 95% CI;

1.7-5.7).

Table 2. Multivariate analysis for independent factors associated with intimate partner violence among study participants

Overall, 268 (67%) participants accepted

that a

wife should always follow her husband’s instructions

irrespective of her will and 74 (18.5%) women

agreed that violence against wife was justified if she

did not follow her husband’s instructions.

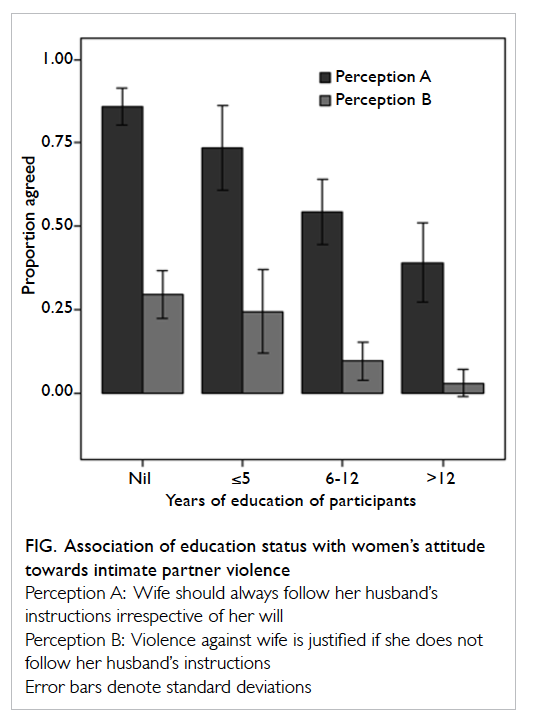

The association of women’s perspective

towards husband’s dominance and use of violence

against wife with the number of years of school

attended by women is shown in the Figure. As the

number of years of schooling increased, there was

a significant decline in the proportion of women

who were in favour of husbands’ dominance over

wives, and those who accepted violence against

wives (Chi squared, P<0.001). The Figure depicts

that the majority of the illiterate women (over 75%)

agreed that wife should always follow her husband’s

instructions irrespective of her will, and about 30%

believed that violence against a wife was justified if

she did not follow her husband’s instructions. On

the other hand, less than 5% of the women who had

more than 12 years of education thought that IPV

was justified if the husband’s instructions were not

followed.

Discussion

Violence against women is being

increasingly

identified as a major contributor to the ill health and

mortality among women.3 10 Despite the imperative

nature of the problem, there is lack of adequate

information on IPV against women in Pakistan. In

the current study, we have explored the proportion

of women abused by their intimate partners and

have identified factors significantly associated with

such acts of abuse.

In this study, approximately one third of

the women (35%) reported being ever physically/verbally violated by their husbands. Other studies

from Pakistan15

16 have also reported similar findings,

with approximately one third to one half of the

participants experiencing some form of violence

from intimate partners. However, a study

conducted in Karachi, Pakistan, among 400 married

women showed that the prevalence of IPV (physical

violence) was 80%.17 A

possible explanation for this

high magnitude of IPV prevalence could be the fact

that the participants were recruited from low socio-demographic

background communities that may be

associated with increased perpetuation of violence

and vulnerability to the victimisation of violence.

The education status of both the partners

has been observed to have significant influence on

the prevalence of IPV.19 20 21 Provision of education

undoubtedly plays a protective role against IPV.

Empowering women through social networking

along with income earning improves their capacity to access

information and resources available in

society, and seek help in case of spousal abuse.19

The results of the current study also clearly indicate

a positive association between the literacy levels

of husband and wife and IPV victimisation among

women. Education also imparts a protective role

through influencing the perspectives of individuals,

and societies in general, against the acceptability

of mistreatment towards women.19

A climate

of tolerance towards IPV makes it easier for

perpetrators to persist with their violent behaviour.22

Education inculcates a sense of self-respect and self-reliance

in women, enhancing their capacity to make

appropriate decisions regarding various aspects

of their lives confidently and autonomously.11

On the other hand, lack of education not only

deprives women from acknowledging their rights

but, instead, stigmatises their thinking on gender

roles and makes them more accepting towards use

of force to impose these roles.23

24 This effect was

observed in previous studies in which low level of

education was associated with women’s acceptance

of wife battering, whereas higher education level

was negatively associated with tolerance of wife

beating. Furthermore, educated women were most

protected against violence.23

24 This is also reflected

in the findings of this study in that acceptance

and tolerance towards husband’s mistreatment

and control over the wife markedly declined as the

education level of the women improved.

The results of the current study also

indicate

that women whose husbands smoke or consume

other substances of abuse experience increased

levels of IPV. This is consistent with the findings

of previous studies20 25 26 which showed that smoking,

alcohol consumption, and using other substances

of abuse were strongly associated with IPV. Substance abuse, including smoking and alcohol

consumption, may be directly responsible for

IPV by affecting cognition, reducing self-control,

perpetuating aggression and may also induce stress

and unhappiness in relationships, thereby, further

increasing the risk of violence and conflict.26

This study has some limitations. It was

conducted in selective family practice clinics which

may have underestimated the results due to under-reporting.

Since these clinics are situated in urban

areas of a single city, the participants may not

represent the population at large. Moreover, the

response rate was low in this study (77%) due to the

sensitive nature of the issue. There is also a chance

of selection bias. As this was a cross-sectional study,

temporality or causality could not be established.

Owing to the cultural and social restrictions, we did

not enquire about sexual abuse. Moreover, due to

sensitivity of the issue, there may have been under-reporting

of such information. We had asked about

the abuse ever in the lifetime; therefore, there is some

possibility of recall bias as well. Hence, the actual

burden of the problem may be higher than what we

have reported. Finally, the questionnaire used in this

study is not a validated tool, so there is a chance of

information bias in the study.

Conclusion

In the light of the above findings, it is

imperative

that VAW be considered a major public health

concern. The prevention of VAW can be achieved

through comprehensive, multifaceted, and

integrated approaches that require joint efforts by

the government, policy-makers, social workers,

religious scholars, educationalists, and public health

practitioners. In this respect, the role of education

is greatly emphasised in changing the perspectives

of individuals and societies against IPV. Family

physicians, being the first-line doctors and health

care providers, should be well trained in screening

for IPV and providing instantaneous care to the

victims by catering to their psychological needs to prevent poor

mental health outcomes.

References

1. Hogan MC, Foreman KJ, Naghavi M,

et al. Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980-2008: a

systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development

Goal 5. Lancet 2010;375:1609-23. CrossRef

2. Heise L. Violence against women:

the hidden health burden. World Health Stat Q 1993;46:78-85.

3. Carolissen R. World report on

violence and health. S Afr Med J 2003;93:272.

4. Sarkar NN. The impact of

intimate partner violence on women’s reproductive health and

pregnancy outcome. J Obstet Gynecol 2008;28:266-71. CrossRef

5. Bailey BA, Daugherty RA.

Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: incidence and

associated health behaviors in a rural population. Matern Child

Health J 2007;11:495-503. CrossRef

6. Ruiz-Pérez I, Plazaola-Castaño

J, Del Río-Lozano M. Physical health consequences of intimate

partner violence in Spanish women. Eur J Public Health

2007;17:437-43. CrossRef

7. Abrahams N, Jewkes R, Martin LJ,

Mathews S, Vetten L, Lombard C. Mortality of women from intimate

partner violence in South Africa: a national epidemiological

study. Violence Vict 2009;24:546-56. CrossRef

8. Bair-Merritt MH, Blackstone M,

Feudtner C. Physical health outcomes of childhood exposure to

intimate partner violence: a systematic review. Pediatrics

2006;117:e278-90. CrossRef

9. Graham-Bermann SA, Gruber G,

Howell KH, Girz L. Factors discriminating among profiles of

resilience and psychopathology in children exposed to intimate

partner violence (IPV). Child Abuse Negl 2009;33:648-60. CrossRef

10. Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA,

Ellsberg M, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner violence:

findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and

domestic violence. Lancet 2006;368:1260-9. CrossRef

11. Abramsky T, Watts CH,

Garcia-Moreno C, et al. What factors are associated with recent

intimate partner violence? Findings from the WHO multi-country

study on women’s health and domestic violence. BMC Public Health

2011;11:109. CrossRef

12. Ahmad F, Hogg-Johnson S,

Stewart DE, Levinson W. Violence involving intimate partners:

prevalence in Canadian family practice. Can Fam Physician

2007;53:460-8.

13. Chandra PS, Satyanarayana VA,

Carey MP. Women reporting intimate partner violence in India:

associations with PTSD and depressive symptoms. Arch Womens Ment

Health 2009;12:203-9. CrossRef

14. Silverman JG, Decker MR, Gupta

J, Kapur N, Raj A, Naved RT. Maternal experiences of intimate

partner violence and child morbidity in Bangladesh: evidence from

a national Bangladeshi sample. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med

2009;163:700-5. CrossRef

15. Andersson N, Cockcroft A,

Ansari U, et al. Barriers to disclosing and reporting violence

among women in Pakistan: findings from a national household survey

and focus group discussions. J Interpers Violence 2010;25:1965-85. CrossRef

16. Farid M, Saleem S, Karim MS,

Hatcher J. Spousal abuse during pregnancy in Karachi, Pakistan.

Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2008;101:141-5. CrossRef

17. Ali TS, Bustamante-Gavino I.

Prevalence of and reasons for domestic violence among women from

low socioeconomic communities of Karachi. East Mediterr Health J

2007;13:1417-26.

18. Shaikh MA. Domestic violence

against women-perspective from Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc

2000;50:312-4.

19. Boyle MH, Georgiades K, Cullen

J, Racine Y. Community influences on intimate partner violence in

India: women’s education, attitudes towards mistreatment and

standards of living. Soc Sci Med 2008;69:691-7. CrossRef

20. Ntaganira J, Muula AS, Siziya

S, Stoskopf C, Rudatsikira E. Factors associated with intimate

partner violence among pregnant rural women in Rwanda. Rural

Remote Health 2009;9:1153.

21. Vives-Cases C, Alvarez-Dardet

C, Gil-González D, Torrubiano-Domínguez J, Rohlfs I, Escribà-Agüir

V. Sociodemographic profile of women affected by intimate partner

violence in Spain [in Spanish]. Gac Sanit 2009;23:410-4. CrossRef

22. Seth P, Raiford JL, Robinson

LS, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Intimate partner violence and other

partner-related factors: correlates of sexually transmissible

infections and risky sexual behaviours among young adult African

American women. Sexual Health 2010;7:25-30. CrossRef

23. Rani M, Bonu S. Attitudes

toward wife beating a cross-country study in Asia. J Interpers

Violence 2009;24:1371-97. CrossRef

24. Dhaher EA, Mikolajczyk RT,

Maxwell AE, Kramer A. Attitudes toward wife beating among

Palestinian women of reproductive age from three cities in West

Bank. J Interpers Violence 2010;25:518-37. CrossRef

25. Easton CJ, Weinberger AH,

McKee SA. Cigarette smoking and intimate partner violence among

men referred to substance abuse treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse

2008;34:39-46. CrossRef

26. Stuart GL, Temple JR,

Follansbee KW, Bucossi MM, Hellmuth JC, Moore TM. The role of drug

use in a conceptual model of intimate partner violence in men and

women arrested for domestic violence. Psychol Addict Behav

2008;22:12-24. CrossRef