Hong

Kong Med J 2014 Aug;20(4):274–8 | Epub

28 Feb 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134062

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

The association between clinical parameters and

glaucoma-specific quality of life in Chinese primary open-angle

glaucoma patients

Jacky WY Lee, FRCS1; Catherine WS Chan, MPhil1;

Jonathan CH Chan, FRCS2; Q Li, PhD1; Jimmy

SM Lai, MD1

1 Department of

Ophthalmology, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam,

Hong Kong

2 Department of

Ophthalmology, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong

Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Jacky WY Lee (jackywylee@gmail.com)

Abstract

Objective: To

investigate the association between

clinical measurements and glaucoma-specific quality

of life in Chinese glaucoma patients.

Design: Cross-sectional

study.

Setting: An academic

hospital in Hong Kong.

Patients: A Chinese

translation of the Glaucoma

Quality of Life–15 questionnaire was completed

by 51 consecutive patients with bilateral primary

open-angle glaucoma. The binocular means of

several clinical measurements were correlated with

Glaucoma Quality of Life–15 findings using Pearson’s

correlation coefficient and linear regression. The

measurements were the visual field index and

pattern standard deviation from the Humphrey

Field Analyzer, Snellen best-corrected visual acuity,

presenting intra-ocular pressure, current intra-ocular

pressure, average retinal nerve fibre layer thickness

via optical coherence tomography, and the number

of topical anti-glaucoma medications being used.

Results: In these

patients, there was a significant

correlation and linear relationship between a poorer

Glaucoma Quality of Life–15 score and a lower

visual field index (r=0.3, r2=0.1,

P=0.01) and visual

acuity (r=0.3, r2=0.1, P=0.03). A

thinner retinal

nerve fibre layer also correlated with a poorer Glaucoma Quality

of Life–15 score, but did not

attain statistical significance (r=0.3, P=0.07). There

were no statistically significant correlations for the

other clinical parameters with the Glaucoma Quality

of Life–15 scores (all P values being >0.7). The three

most problematic activities affecting quality of life

were “adjusting to bright lights”, “going from a light

to a dark room or vice versa”, and “seeing at night”.

Conclusion: For Chinese

primary open-angle

glaucoma patients, binocular visual field index and

visual acuity correlated linearly with glaucoma-specific

quality of life, and activities involving dark

adaptation were the most problematic.

New knowledge added by this

study

- A lower visual field index and poorer visual acuity correlated with a poorer glaucoma-specific quality of life in Chinese primary open-angle glaucoma patients.

- The most problematic activities affecting quality of life in glaucoma patients were “adjusting to bright lights”, “going from a light to a dark room or vice versa”, and “seeing at night”.

- In busy clinical settings, the visual field index serves as a quick reference for glaucoma-specific quality of life, and can identify patients who may warrant more formal assessment for psychosocial support.

- Lifestyle modifications for glaucoma patients can include more light in dark areas and adjusting curtains and mirrors to reduce glare, so as to make the transition from different lighting conditions more acceptable.

Introduction

In clinical practice, much time is spent on

measuring

the clinical parameters of glaucoma including the

intra-ocular pressure (IOP), visual acuity (VA), visual

field, and retinal nerve fibre layer (RNFL) thickness.

What is often neglected is the quality of life (QOL)

of patients and how well they live with their disease

on a day-to-day basis. Glaucoma affects 80 million people

worldwide.1 It is a chronic

and irreversible

disease with a heavy burden on visual function and

vision, besides being one of the most important

constituents affecting QOL.2

3 4

Recourse to QOL questionnaires in glaucoma

can be broadly divided into general health–related,

vision-specific, or glaucoma-specific.5

Quality-of-life

assessment in glaucoma patients is as important as the clinical

parameters used to measure glaucoma

progression, because it reflects the impact of

the ocular disease on the patient as a whole and

may also be an indicator of whether the disease is

advancing.4 6

7 8

9

Using generic QOL assessments, glaucoma

was found to have deleterious impact as other

systemic chronic diseases like osteoporosis, diabetes,

or dementia.10 However,

such generic tests do not

address the end points of glaucoma, such as visual

impairment and visual field constriction, for which

reason their robustness and specificity are limited.10

There are approximately 18 different patient-reported

QOL assessments specific to glaucoma.

Among these, the Glaucoma Quality of Life–15

Questionnaire (GQL-15) and the Vision and Quality

of Life Index have been found most satisfactory in

terms of content, validity, and reliability.11

Thus, the

aim of this study was to investigate the correlations

between clinical parameters and glaucoma-specific

QOL in Chinese patients with bilateral primary open-angle glaucoma

(POAG).

Methods

For this cross-sectional study, consecutive

patients with bilateral POAG were recruited from an academic

hospital in Hong Kong. The diagnosis of POAG was

based on an open angle on gonioscopy, a presenting

IOP of >21 mm Hg, and either a glaucomatous visual

field loss on at least two Humphrey visual field tracings

using the 24-2 SITA fast protocol (Humphrey

Instruments, Inc, Zeiss Humphrey, San Leandro

[CA], US) or RNFL thinning on Spectralis Optical

Coherence Tomography (Heidelberg Engineering,

Carlsbad [CA], US). Patients were excluded if they

had unilateral disease, concomitant ocular diseases

that significantly affected their vision (amblyopia,

mature cataract affecting the accuracy of glaucoma

investigations). Patients were also excluded if they

had other corneal or retinal pathologies, or if they

were unable to yield reliable visual field results. Their

IOPs were determined using Goldmann applanation

tonometry.

The GQL-15 questionnaire is

glaucoma-specific,

and assesses patient-perceived visual

disability in 15 daily tasks responded to in writing.

The tasks addressed four aspects of visual disability:

(1) central and near vision; (2) peripheral vision; (3)

dark adaptation and glare; and (4) outdoor mobility.

A 5-point rating scale for the level of difficulty of each

task can yield a total score of 0 to 75. Higher scores

signify a lower QOL. The GQL-15 was translated

into traditional Chinese text and distributed to

participating patients. For illiterate patients, the

items were read out to them in Cantonese dialect.

The questionnaire was translated from English to

Chinese by an investigator who was fluent in both

English and Chinese. The translated questionnaire

was checked for discrepancies by a second

investigator and a consensus was reached to develop

a draft Chinese questionnaire. A third investigator

then back-translated the draft Chinese questionnaire

into English; the back-translated draft and the

original version were then compared. Discrepancies

were amended and gave rise to the final Chinese

version. The questionnaire was then tested on five

POAG patients of varying gender and age. Patients

were asked to complete the questionnaire, and offer

their own interpretation of its contents and whether

any alternative wording should be used.

The D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus test was

used

to test for normality. Nearly half of the parameters

passed the normality testing. The means of several

clinical parameters were calculated for the two eyes

and correlated with the GQL-15 using Pearson’s

correlation coefficient and linear regression analysis.

The selected parameters were the visual field index

(VFI) and pattern standard deviation (PSD) from the

Humphrey Field Analyzer, the Snellen best-corrected

VA, the presenting IOP, current IOP, average RNFL

thickness via optical coherence tomography, as well

as the number of topical anti-glaucoma medications

being used. t Tests were used to test for differences

between the mean GQL-15 scores between males

and females. Data were expressed as mean ± standard

deviation (SD). Any P value of <0.05 was accepted as

statistically significant.

Our institutional review board granted

ethics

approval for the study and informed consent was

obtained from each patient prior to the start of the

study.

Results

Fifty-one patients with bilateral POAG were

recruited, all of whom were Chinese. Their mean

(± SD) age was 65.8 ± 12.1 years and the male-to-female

ratio was 1.1:1.

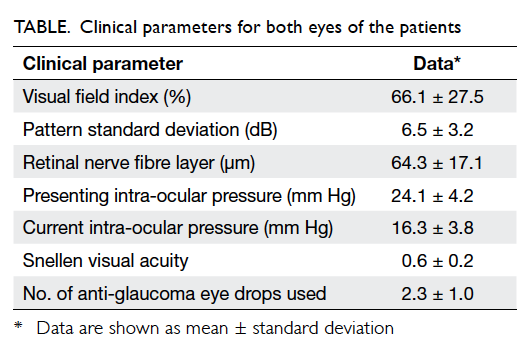

The means of their clinical parameters for

both

eyes are shown in the Table.

Their mean GQL-15

score was 26.0 ± 11.6 (out of 75). The three most

problematic activities reported for all patients

belonged to: item 4 “adjusting to bright lights” (mean

score, 2.3 ± 1.3); item 6 “going from a light to a dark

room or vice versa” (mean score, 2.3 ± 1.3); and item

2 “seeing at night” (mean score, 2.2 ± 1.2).

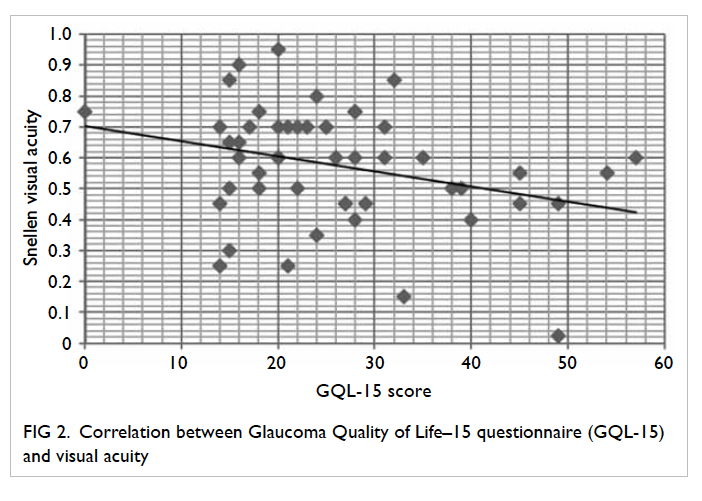

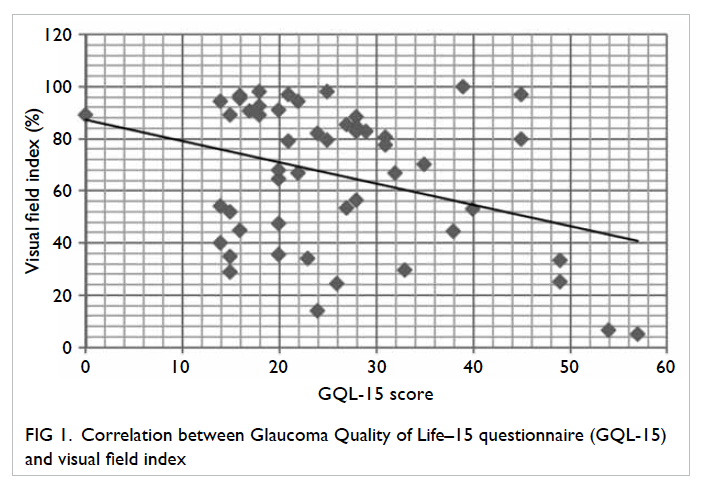

There was a moderately significant

correlation

between a lower VFI and a poorer GQL-15 score

(r=0.3, P=0.01; Fig

1). Likewise, a poorer VA

correlated significantly with a poorer GQL-15 score

(r=0.3, P=0.03; Fig

2). These two correlations seemed

to follow a linear pattern such that linear regression

analysis showed a weak linear relationship between

a poorer GQL-15 score and a lower VFI (r2=0.1,

P=0.01) and a poorer VA (r2=0.1, P=0.03).

Fig 1. Correlation between Glaucoma Quality of Life–15 questionnaire (GQL-15) and visual field index

A thinner RNFL appeared to be associated

with

a poorer GQL-15 score but the correlation did not

attain statistical significance (r=0.3, P=0.07). In terms

of pressure control, a higher presenting IOP showed

a trend towards correlation with a poorer GQL-15

score (r=0.2) as did a lower current IOP (r= 0.2)

and

a greater number of anti-glaucoma eye drops used

(r=0.1). However, none of these correlations reached

statistical significance (all P>0.7). On comparing

GQL-15 scores between male and female glaucoma

patients, no significant difference was found (P=0.3,

t test).

Discussion

Various studies have associated QOL with

visual field

impairment.8 12

Odberg et al13 simply

categorised

visual field defects into “normal”, “having a restricted

scotoma”, or “having a field defect large enough to be

of visual significance”, and found a weak-to-moderate

correlation between such visual field defects and

subjective visual disabilities. The Collaborative

Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study later found

that at the time of diagnosis, patients’ visual fields

correlated only modestly with a health-related QOL

questionnaire and that of VFIs; mean

deviation (MD) showed better correlation with QOL

than PSD, corrected pattern SD,

or short-term fluctuation.14

Nelson et al4 found

that the GQL-15 scores, and especially the subsets

pertaining to glare, correlated significantly with MD,

even for patients with mild disease. Furthermore,

those with moderate and severe visual field loss had similar

GQL-15 scores, suggesting a threshold

for disability may be reached up to a certain level of

glaucoma severity4 or

represent adaptation to loss

of visual function. Similarly, Goldberg et al15

have

found that the GQL-15 scores correlated with VA,

MD, the number of binocular points of <10 dB, and

that QOL tended to decrease with disease severity.

Whilst MD is commonly correlated with QOL in

glaucoma patients, it has the drawback of not being

specific enough to represent the limitations caused

by glaucoma alone, since it may also be affected by

global defects like cataract. On the other hand, using

PSD eliminates the factor of global defects, though

it is not sensitive in advanced glaucoma, where the

entire field is globally depressed.

Thus in this study, we utilised the VFI,

which

is a percentage summarising the overall visual field

status compared to age-adjusted visual fields. The

VFI emphasises the importance of the central field.

It is less affected by media opacities (cataracts), and

is more accurate than MD for monitoring glaucoma

progression.16 17

Few studies have used VFI to correlate

with QOL in glaucoma. Sawada et al18

reported that

VFI correlated with QOL via the 25-item National

Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI

VFQ-25) and that the correlation was better than

with MD. Our study found a statistically significant

correlation between the reduction in mean binocular

VFI and a poorer GQL-15 score and that VFI was

a better indicator of glaucoma-specific QOL than

RNFL thickness, IOP, or PSD on visual field. We chose

to use PSD rather than MD in our analysis because

the latter could be affected by any global obstruction

to vision like cataract, whereas PSD is more specific

for inter-field variability. However, the two clinical

parameters that achieved a significant correlation

with the GQL-15 score were binocular VFI and VA,

and both parameters were also associated with the

GQL-15 score in a linear manner.

Intra-ocular pressure control did not

correlate

significantly with QOL although a higher IOP on

presentation seemed to produce a lower QOL score,

and interestingly a lower current IOP seemed to

correlate with a poorer QOL. This unique finding may

indicate that those with a lower current IOP have had

glaucoma for longer or have more advanced disease

warranting more aggressive pressure reduction.

Furthermore, those using more anti-glaucoma eye

drops seemed to have a lower QOL score, but these

correlations were weak and did not reach statistical

significance.

Patient perceptions of disease and methods

of coping are heavily influenced by culture and

ethnicity. Thus, Singapore Chinese glaucoma patients

were more accepting of their daily disabilities than

corresponding American Caucasians.19

Literature

pertaining to Chinese glaucoma patients is sparse.

Wu et al20 found that

Chinese glaucoma patients were particularly concerned about the

uncertainties

of treatment, the prognosis, and passing on of the

disease to family members. Lin and Yang21

reported

a correlation with MD and the Medical Outcomes

Study Short-Form 36 Health Survey and the NEI

VFQ-25. Whilst clinical data provide evidence

of structural and functional damage of the optic

nerve, they do not address the impact of disease

on patients. The correlation of objective clinical

measurements to QOL is particularly useful, because

it gives ophthalmologists in a busy clinical setting an

overall impression of glaucoma-specific QOL. This

can enable them to recommend environmental and

lifestyle modifications to minimise obstacles and

maximise the period of independence.5

Our study

found that in Chinese glaucoma patients, the most

problematic aspects of coping were “adjusting to

bright lights”, “going from a light to a dark room

or vice versa”, and “seeing at night”. Interestingly,

all these activities belong to the realm of dark

adaptation. Hence, environmental modifications can

potentially help to reduce glare.4

Furthermore, an

estimation of QOL from clinical parameters can allow

ophthalmologists to more readily identify patients

with a poorer QOL needing more psychosocial

support. Interestingly, it has been reported that

POAG itself is associated with anxiety, depression,

and hypochrondriasis22 and

a low GQL-15 score has

also been identified as a predictor for depression.23

One limitation of our study was that it was

cross-sectional and looked at POAG patients with

varying degrees of severity. A longitudinal study

would have provided additional information about

the changes in QOL throughout different stages

of the disease. A second limitation was that the

population received heterogeneous treatments

(lasers and surgeries). However, as the aim of this

study did not involve evaluating the side-effects of

glaucoma treatments and since the GQL-15 too

did not target treatment side-effects, we did not

consider it necessary to exclude those who had

undergone such treatments previously. Rather,

we opted to include a more heterogeneous POAG

population to make the results more generalisable

and representative. A third limitation was that no

single test is perfect; the GQL-15 mainly focuses on

visual activities, which is only one aspect of QOL.

Conceivably, such a questionnaire only reflects

patient confidence to perform certain tasks rather

than the actual difficulties experienced. Nevertheless,

it has been shown that patients’ loss of confidence

often precedes their perceptions of difficulty.24

To the best of our knowledge, this is one

of the

few studies reporting a significant correlation and a

linear relationship between VFI and the glaucoma-specific

GQL-15 score in the Chinese POAG

patients. This study also identified dark adaptation

as the most challenging visual issue pertinent to Chinese POAG

patients.

Declaration

No conflicts of interest were declared by

the authors.

References

1. Mansberger SL, Demirel S. Early

detection of glaucomatous visual field loss: why, what, where, and

how. Ophthalmol Clin North Am 2005;18:365-73, v-vi. CrossRef

2. Beauchamp CL, Beauchamp GR,

Stager DR Sr, Brown MM, Brown GC, Felius J. The cost utility of

strabismus surgery in adults. J AAPOS 2006;10:394-9. CrossRef

3. Brown GC, Brown MM, Sharma S, et

al. The burden of age-related macular degeneration: a value-based

medicine analysis. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 2005;103:173-86.

4. Nelson P, Aspinall P,

Papasouliotis O, Worton B, O’Brien C. Quality of life in glaucoma

and its relationship with visual function. J Glaucoma

2003;12:139-50. CrossRef

5. Spaeth G, Walt J, Keener J.

Evaluation of quality of life for patients with glaucoma. Am J

Ophthalmol 2006;141(1 Suppl):S3-14. CrossRef

6. Jampel HD, Schwartz A, Pollack

I, Abrams D, Weiss H, Miller R. Glaucoma patients' assessment of

their visual function and quality of life. J Glaucoma

2002;11:154-63. CrossRef

7. Janz NK, Wren PA, Lichter PR,

Musch DC, Gillespie BW, Guire KE. Quality of life in newly

diagnosed glaucoma patients: the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma

Treatment Study. Ophthalmology 2002;108:887-97; discussion 898. CrossRef

8. Parrish RK 2nd, Gedde SJ, Scott

IU, et al. Visual function and quality of life among patients with

glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 1997;115:1447-55. CrossRef

9. Gutierrez P, Wilson MR, Johnson

C, et al. Influence of glaucomatous visual field loss on

health-related quality of life. Arch Ophthalmol 1997;115:777-84. CrossRef

10. Mills T, Law SK, Walt J,

Buchholz P, Hansen J. Quality of life in glaucoma and three other

chronic diseases: a systematic literature review. Drugs Aging

2009;26:933-50. CrossRef

11. Vandenbroeck S, De Geest S,

Zeyen T, Stalmans I, Dobbels F. Patient-reported outcomes (PRO's)

in glaucoma: a systematic review. Eye (Lond) 2011;25:555-77. CrossRef

12. Lee BL, Gutierrez P, Gordon M,

et al. The Glaucoma Symptom Scale. A brief index of

glaucoma-specific symptoms. Arch Ophthalmol 1998;16:861-6. CrossRef

13. Odberg T, Jakobsen JE,

Hultgren SJ, Halseide R. The impact of glaucoma on the quality of

life of patients in Norway. II. Patient response correlated to

objective data. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2001;79:121-4. CrossRef

14. Mills RP, Janz NK, Wren PA,

Guire KE. Correlation of visual field with quality-of-life

measures at diagnosis in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma

Treatment Study (CIGTS). J Glaucoma 2001;10:192-8. CrossRef

15. Goldberg I, Clement CI, Chiang

TH, et al. Assessing quality of life in patients with glaucoma

using the Glaucoma Quality of Life–15 (GQL-15) questionnaire. J

Glaucoma 2009;18:6-12. CrossRef

16. Bengtsson B, Heijl A. A visual

field index for calculation of glaucoma rate of progression. Am J

Ophthalmol 2008;145:343-53. CrossRef

17. Casas-Llera P, Rebolleda G,

Muñoz-Negrete FJ, Arnalich-Montiel F, Pérez-López M,

Fernández-Buenaga R. Visual field index rate and event-based

glaucoma progression analysis: comparison in a glaucoma

population. Br J Ophthalmol 2009;93:1576-9. CrossRef

18. Sawada H, Fukuchi T, Abe H.

Evaluation of the relationship between quality of vision and the

visual function index in Japanese glaucoma patients. Graefes Arch

Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2011;249:1721-7. CrossRef

19. Saw SM, Gazzard G, Au Eong KG,

Oen F, Seah S. Utility values in Singapore Chinese adults with

primary open-angle and primary angle-closure glaucoma. J Glaucoma

2005;14:455-62. CrossRef

20. Wu PX, Guo WY, Xia HO, Lu HJ,

Xi SX. Patients' experience of living with glaucoma: a

phenomenological study. J Adv Nurs 2011;67:800-10. CrossRef

21. Lin JC, Yang MC. Correlation

of visual function with health-related quality of life in glaucoma

patients. J Eval Clin Pract 2010;16:134-40. CrossRef

22. Erb C, Thiel HJ, Flammer J.

The psychology of the glaucoma patient. Curr Opin Ophthalmol

1998;9:65-70. CrossRef

23. Skalicky S, Goldberg I.

Depression and quality of life in patients with glaucoma: a

cross-sectional analysis using the Geriatric Depression Scale–15,

assessment of function related to vision, and the Glaucoma Quality

of Life–15. J Glaucoma 2008;17:546-51. CrossRef

24. Nelson P, Aspinall P, O’Brien

C. Patients’ perception of visual impairment in glaucoma: a pilot

study. Br J Ophthalmol 1999;83:546-52. CrossRef