Hong Kong Med J 2014;20:213–21 | Number 3, June 2014 | Epub 9 May 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134181

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Social obstetrics: non-local expectant mothers

admitted through accident and emergency department in a public

hospital in Hong Kong

WK Yung, MB, BS, FHKAM (Obstetrics and

Gynaecology)1; Winnie Hui, MB, BS1; YT

Chan, MB, BS, MRCOG1; TK Lo, FHKAM (Obstetrics and

Gynaecology)1; SM Tai, BSc, MSc1; C Sing,

BSc, MSc1; YY Lam, MB, BS, FHKAM (Paediatrics)2;

CM Lo, FRCP (Irel), FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)3; WL Lau,

MB, BS, FRCOG1; WC Leung, MD, FHKAM (Obstetrics and

Gynaecology)1

1 Department of Obstetrics

and Gynaecology, Kwong Wah Hospital, 25 Waterloo Road, Hong Kong

2 Department of

Paediatrics, Kwong Wah Hospital, 25 Waterloo Road, Hong Kong

3 Department of Accident

and Emergency, Kwong Wah Hospital, 25 Waterloo Road, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr WC Leung (leungwc@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Objectives: To review

the pregnancy outcomes of non-booked, non-local pregnant women

delivering in Kwong Wah Hospital via admission to the Accident

and Emergency Department 1 year after the announcement by the

Hospital Authority to stop antenatal booking for non-eligible

persons; and to perform a literature review of local studies

about non-eligible person deliveries over the last decade.

Design: Case series.

Setting: A public

hospital in Hong Kong.

Participants: All women

who held the People’s Republic of China passport or the two-way

permit and those non-eligible persons whose spouses were Hong

Kong Identity Card holders, who delivered in Kwong Wah Hospital

from 1 April 2011 to 31 March 2012.

Results: Overall, 219

women who were non-eligible persons delivered 221 live births

during the study period. Compared with the annual statistics of

Kwong Wah Hospital in 2011, non-local mothers were of higher

parity; more likely to have hypertensive disease (including

pre-eclamptic toxaemia), preterm deliveries (ie at <37

weeks), babies needing admission to the special care baby unit,

and macrosomic babies (ie weighing >4.0 kg). The rates of

induction of labour and caesarean section were lower in this

group. There was no significant difference in the maternal and

neonatal outcomes between women who had no booking and those who

had a booking in another Hospital Authority or private hospital.

There were many incidents of near-miss obstetric complications

or suboptimally managed obstetric conditions due to lack of

well-structured and continuous antenatal care in this group of

non-eligible persons.

Conclusion: Non-eligible

person delivering babies in Hong Kong has become a social

obstetrics phenomenon. Despite the introduction of policies,

reduction in the number of deliveries (quantity) did not improve

the obstetric outcomes (quality). Health care professionals

should continue to be prepared for managing the potential

near-miss clinical complications in this group of ‘travelling

mothers’.

New knowledge added by this

study

- Non-eligible person (NEP) delivery in Hong Kong has been a social obstetric phenomenon specific to this region (Hong Kong SAR) because of political circumstances. Despite the reduction in the quantity, these non-booked deliveries continue to run a high risk of adverse obstetric outcomes due to difficulties experienced by the expectant mothers in accessing a well-structured obstetric service.

- Regardless of the number of patient load, the NEP women remain potentially at risk of obstetric complications. Health care professionals should be prepared for managing the near-miss conditions.

Introduction

The influx of expectant mothers from

Mainland China leading to overwhelming of the local obstetric and

neonatal services has been a hot topic of discussion in the media

in the past few years. In 2001, the Hong Kong Court of Final

Appeal delivered a unanimous opinion by which Chong Fung-yuen, a

Chinese baby born while his Mainland Chinese parents were in Hong

Kong on two-way permits, was granted residency in Hong Kong. In

addition, in 2003, the Hong Kong SAR Government introduced the

Individual Visit Scheme which allowed travellers from Mainland

China to visit Hong Kong and Macao on an individual basis. Since

the introduction of these policies, there has been a dramatic

increase in the number of ‘traveller’ mothers delivering in Hong

Kong. This ‘birth tourism’—a travel to a country that practises

birthright citizenship or permanent residency in order to give

birth there, so that the child will be a citizen of the

destination country—has significantly influenced the standard

obstetric practice in Hong Kong, resulting in adverse pregnancy

outcomes. We have described this phenomenon as social obstetrics.1 2

3

According to the Hospital Authority (HA)

pay code, there are seven categories of non-eligible person (NEP).

The categories of NE-2 (People’s Republic of China passport or two-way permit holder ‘雙非’) and NE-3 (NEP whose spouse is a Hong Kong Identity Card [HKID] holder ‘單非’) contribute to the majority

of NEP deliveries in public hospitals.

In 2005, the HA launched an obstetric

package to limit the number of non-local women delivering in

public hospitals. The charge was HK$20 000 for 3 days and 2 nights

of hospital stay including delivery. However, this policy did not

discourage ‘traveller’ mothers from delivering in public

hospitals.4

In February 2007, the HA launched a new

obstetric package for non-local expecting mothers. This package

charged almost double (HK$39 000) for the hospitalisation for 3

days and 2 nights. Those who have not booked were additionally

charged.

Unfortunately, the growing number of NEP

deliveries in HA hospitals outweighed the capacity of public

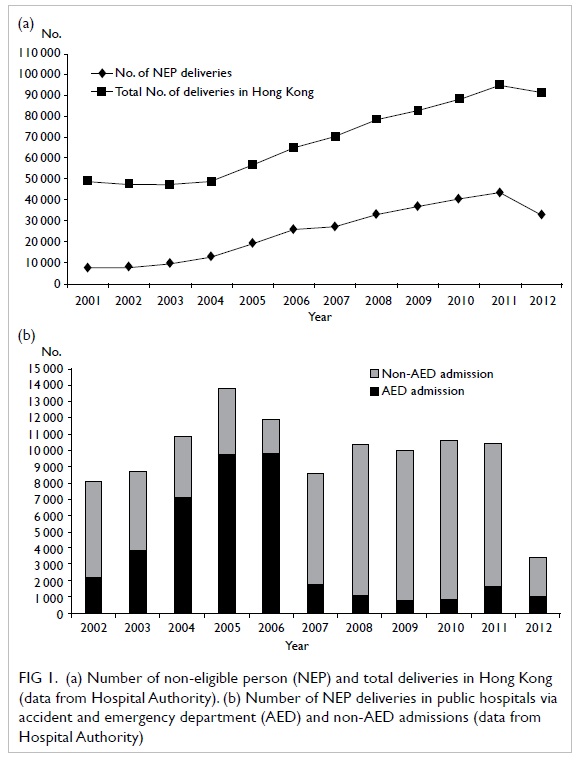

obstetric and neonatal services. In 2010, there were about 88 000

deliveries in the territory, of which 50% were by mainland mothers

(Fig 1a). The total capacity of neonatal

intensive care units (NICUs; about 100 beds) in Hong Kong can only

support an annual delivery rate of 75 000.5 This resulted in the formation of Hong Kong

Obstetric Service Concern Group in March 2011—to urge the Hong

Kong SAR Government to take action in preventing the collapse of

public obstetric and neonatal services. The first remedial measure

was to stop accepting new antenatal booking in HA hospitals from 8

April 2011 till the end of the year. One year later, on 26 April

2012, HA announced that there was no booking quota for non-local

expecting mothers as public service was prioritised for the Hong

Kong citizens to meet the surge of childbirth in the Chinese year

of ‘Dragon’. The non-booked deliveries would be charged HK$90 000

for the 3-days-2-nights package. Lastly, the Government prohibited

antenatal booking of non-local mothers in either public (for NE-2

and NE-3 categories) or private (for NE-2 category) sectors from 1

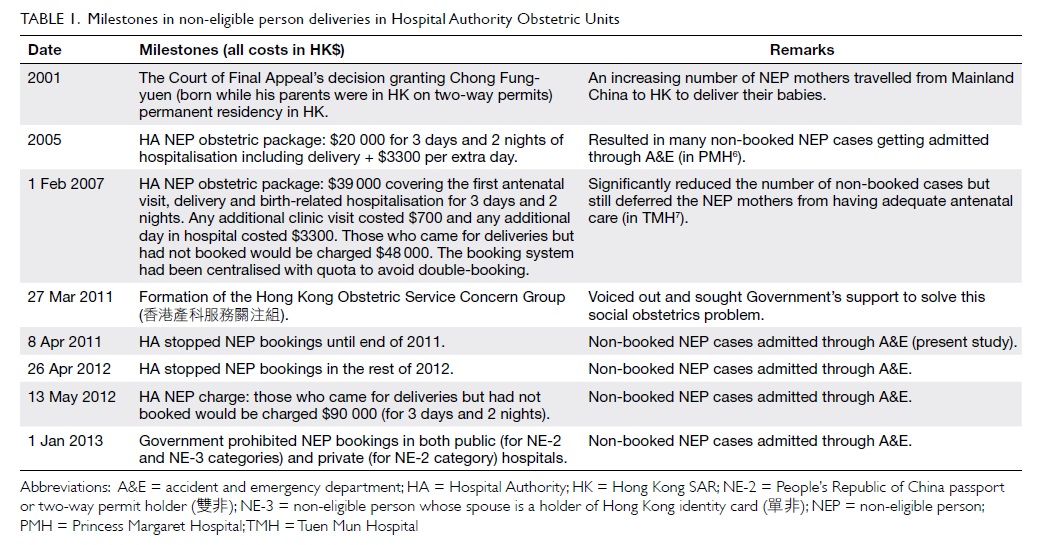

January 2013 onwards (Table 16

7).

Figure 1. (a) Number of non-eligible person (NEP) and total deliveries in Hong Kong (data from Hospital Authority). (b) Number of NEP deliveries in public hospitals via accident and emergency department (AED) and non-AED admissions (data from Hospital Authority)

However, if a pregnant woman, regardless of

her identity card status, attended the accident and emergency

department (AED) of a public hospital, the doctor-on-duty would

assess her condition and offer admission to the obstetric unit if

medically indicated. The admission rate via AED through the years

varied with the implementation of obstetric package and government

policy (Fig 1b). In 2005, when the first obstetric

package was launched, the admission through AED for delivery was

high. The second package in 2007 encouraged antenatal booking,

and, thus, the AED admission rate dropped thereafter. Since April

2011, HA stopped all antenatal bookings for NEP, as a result of

which the total number of NEP deliveries decreased drastically;

however, the proportion of AED admissions increased.

In Kwong Wah Hospital, antenatal booking

for non-local mothers had been stopped since April 2011. The NEP

deliveries in our unit were mainly through AED admission or

transfer from another HA or private hospital.

This retrospective study reviewed the

pregnancy conditions and outcomes of a cohort of non-booked,

non-local women admitted via AED of Kwong Wah Hospital over a

1-year period.

Methods

This study evaluated the demographics,

peripartum events, and pregnancy outcomes of the non-local

pregnant women (NE-2 and NE-3 categories) who were admitted

through AED and who delivered in Kwong Wah Hospital from 1 April

2011 to 31 March 2012. This was the 1-year period after HA’s

announcement (on 8 April 2011) of stopping antenatal booking for

non-local women. The birth registry record of Kwong Wah Hospital

was reviewed. Women who delivered in the captioned period with no

HKID number were identified. Clinical records of the subjects were

retrieved from the central record unit. Only women in NE-2 and

NE-3 categories were recruited.

Clinical notes and electronic patient

records of the subjects were reviewed. The pregnancy conditions

studied included the presenting symptoms, antenatal complications,

gestation at delivery, mode of delivery, intrapartum and

postpartum complications, birth weight of babies, Apgar score,

need for neonatal resuscitation, admission to NICU or special baby

care unit, neonatal morbidities, congenital abnormalities, etc.

Maternal and neonatal outcomes were further analysed according to

their booking status before admission. The annual statistics of

Kwong Wah Hospital 2011 were used as reference.

Statistical analysis

Skewed continuous variables and nearly

normally distributed variables were presented as medians

(interquartile ranges) and means (± standard deviations [SDs]),

respectively. Categorical data were presented as counts and

percentages. Mann-Whitney U test and independent sample t

test were used for comparison of medians and means, respectively.

Pearson Chi squared test or Fisher’s exact test were used for

comparisons of frequencies, where appropriate. All analyses were

performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

(Windows version 16.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US). A P value of

less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the

Kowloon West Cluster Clinical Research Ethics

Committee.

Results

A total of 219 maternities with delivery

were identified during the study period. There were 221 live

births (three pairs of twins) and one stillbirth. Two (0.9%)

pregnancies had been achieved by assisted reproduction. The mean

(± SD) age of women was 29.9 ± 5.6 years. Of the 219 women, 138

(63.0%) were multiparous, 28 (12.8%) of them had had one previous

caesarean delivery, and one (0.5%) had had two previous Caesarean

sections. Overall, 139 (63.5%) women were of NE-2 category and 53

(24.2%) were of NE-3 category; the remaining 27 (12.3%) did not

provide information about their partners. A total of 138 (63.0%)

women had no booking in Hong Kong; 61 (27.9%) women had antenatal

booking in other HA hospitals; and 20 (9.1%) women were booked in

private hospitals but were referred or chose to deliver in HA

hospitals.

The reasons of admission were as follows:

show or with irregular uterine contraction (n=98, 44.7%),

suspected rupture of membranes (n=52, 23.7%), active phase of

labour (n=40, 18.3%), and antenatal complications (n=21, 9.6%;

these included 10 cases of antepartum haemorrhage, five cases of

preterm prelabour rupture of membranes, three cases of concerns on

fetal wellbeing, two cases of maternal pre-eclampsia, and one case

of threatened preterm labour). Five women admitted for postdate

pregnancy requested for delivery. Two pregnancies were delivered

in an ambulance and one on arrival to AED. One pregnancy was a

stillbirth diagnosed after admission.

Routine antenatal blood tests (complete

blood picture, blood group and Rhesus factor, immune status for

hepatitis, syphilis, rubella, and human immunodeficiency virus)

were performed in 147 (67.1%) women. For the rest of the women,

results of blood tests performed in another HA or private hospital

were available via electronic or hard copies. Ultrasound

assessment was performed for 126 (57.5%) women before delivery.

Of the 219 pregnancies, 23 (10.5%) were

delivered before 37 weeks of gestation; two (0.9%) pregnancies

were delivered after 42 weeks of gestation. A total of 141 (64.4%)

women had spontaneous onset of labour; 32 (14.6%) needed induction

of labour, and 22 (10.0%) needed augmentation of labour.

The majority of women (n=182; 83.1%) had

normal vaginal deliveries. Three (1.4%) pregnancies required

instrumental assistance. Caesarean section was performed in 13

(5.9%) pregnancies after labour and 21 (9.6%) without labour. The

success rate of trial of vaginal delivery after one previous

Caesarean section was 50%. There was no uterine scar rupture in

any case. Primary postpartum haemorrhage occurred in 13 (5.9%)

pregnancies. Seven (3.2%) women required blood transfusion. The

mean length of postnatal hospital stay was 2.0 ± 0.4 days.

Peripartum maternal complications were

divided into mild and significant. Mild complications included

seven cases of gestational hypertension, two cases of mild

pre-eclampsia without magnesium sulphate treatment, three cases of

gestational diabetes on insulin treatment, three cases of moderate

thrombocytopenia (platelet count 50-100 x 109 /L), five

cases of retained placenta requiring surgical exploration, five

cases of postpartum haemorrhage managed by medical therapy, three

cases of post-delivery urinary retention, and five cases of

postpartum fever. Significant complications included six cases of

severe pre-eclampsia requiring magnesium sulphate treatment, two

cases of placenta abruptio, two cases of major placenta praevia

type IV, one case of massive primary postpartum haemorrhage

requiring surgical intervention, and two cases of severe

thrombocytopenia (platelet count <50 x 109 /L).

During the study period, there were 121

(54.8%) male and 100 (45.2%) female live births. The mean birth

weight was 3.3 ± 0.5 kg. There were 19 (8.7%) babies with low

birth weight (<2.5 kg); 13 (5.9%) were macrosomic (>4.0 kg).

Two babies required neonatal resuscitation. The admission rates to

the NICU and special care baby unit (SCBU) were 3.7% and 43.8%,

respectively. Overall, 15 (6.8%) babies had minor congenital

abnormalities. Three (1.4%) had major abnormalities, including one

ventricular septal defect, one atrial septal defect, and one

bilateral congenital cataract. Apart from congenital problems, 51

babies had neonatal jaundice requiring phototherapy, 22 had

respiratory complications, 22 had infection episodes, five had

electrolyte disturbance, three had birth trauma, three had

congenital hypothyroidism, three had hypoglycaemia, one had

hypothermia, one had polycythaemia, one had anaemia requiring

blood transfusion, one had neonatal autoimmune thrombocytopenia

requiring intravenous immunoglobulin treatment, and one had

neurological complications. The composite neonatal morbidity rate

was 39.8%.

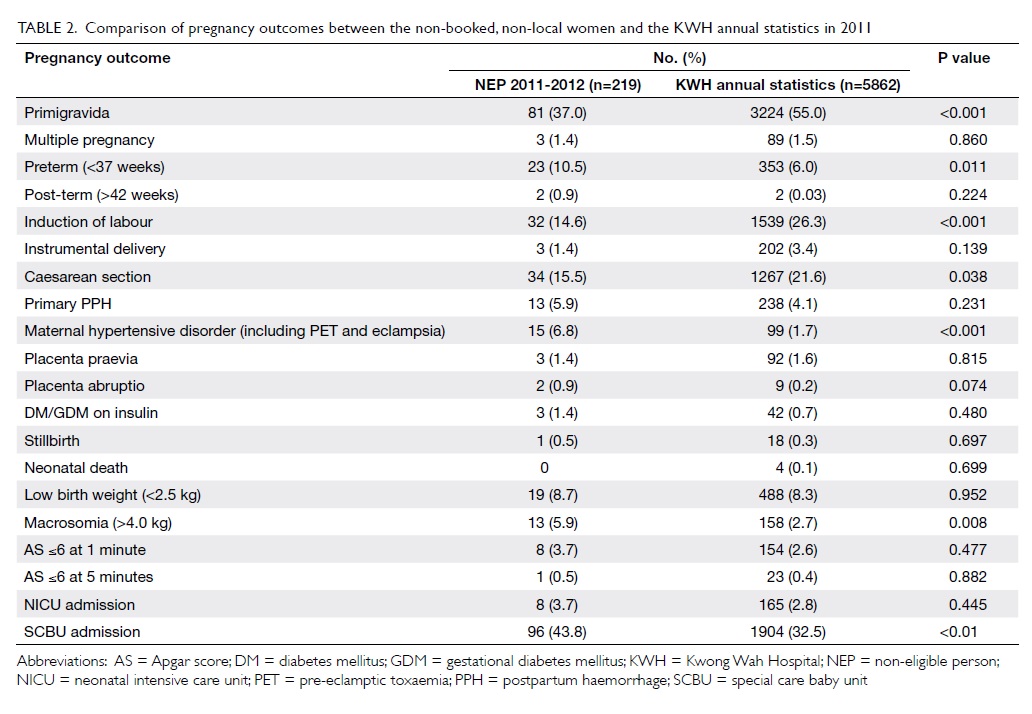

The pregnancy outcomes of the study cohort

were compared with the annual statistics (2011) of Kwong Wah

Hospital, as shown in Table

2. Non-local mothers were of higher

parity; more likely to have hypertensive disease (including

pre-eclamptic toxaemia), preterm delivery (<37 weeks), babies

requiring admission to SCBU, and macrosomic babies (>4.0 kg).

The rate of induction of labour and caesarean section was lower in

this group.

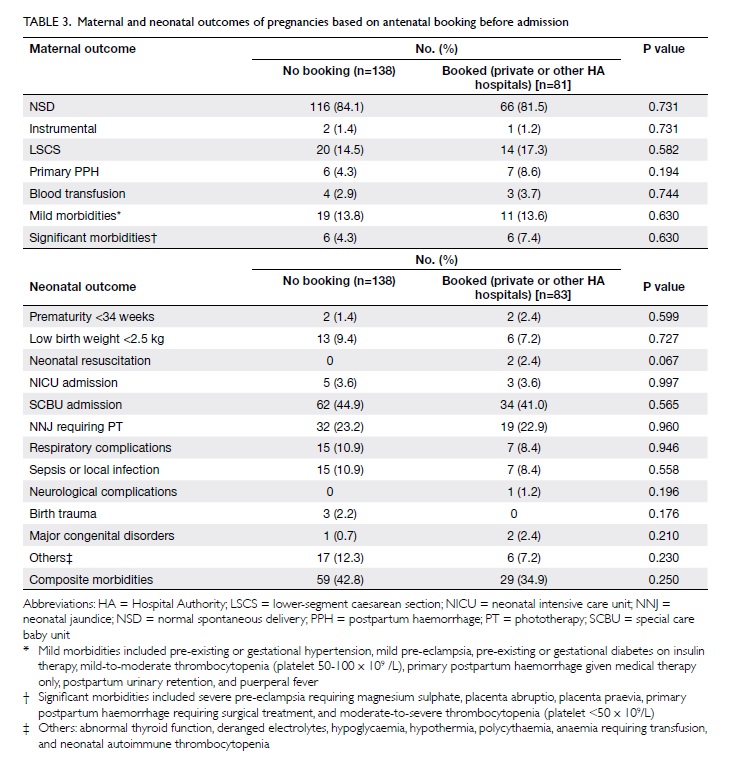

We also analysed the maternal and neonatal

outcomes based on their antenatal booking before admission (ie no

booking versus booking in other HA or private hospitals). We found

that there was no significant difference in maternal and neonatal

outcomes between the two groups. The results are shown in Table

3.

Table 2. Comparison of pregnancy outcomes between the non-booked, non-local women and the KWH annual statistics in 2011

Discussion

Standard obstetric practice is influenced

by social behaviour such as ‘birth tourism’ resulting in adverse

pregnancy outcomes; we have described this phenomenon as social

obstetrics.1 2 3 Some

women came because they wanted to evade the ‘one-child’ policy of

Mainland China. This was reflected in our study which showed that

63% of the NEP mothers were multiparous versus 45% from the

hospital annual statistics. The higher proportion of multiparity

also explained the lower rate of labour induction and caesarean

delivery in the study group. On the other hand, the significantly

higher rates of preterm delivery, hypertensive disease, macrosomic

babies, and SCBU admission suggest that the NEP mothers belonged

to a high-risk group.

In this study cohort, 63.5% of women

belonged to the NE-2 category. Their travelling permit only

allowed a short period of stay. In principle, there could be

shared care between Hong Kong and Mainland China; in reality, this

form of shared care is often suboptimal because of the differences

in clinical practice and culture between the two places. Some

mothers could not make antenatal booking in Mainland China under

the ‘one-child’ policy. Serious conditions may be detected for the

first time during an emergency admission.8

This largely endangers the health of mothers and babies. We have

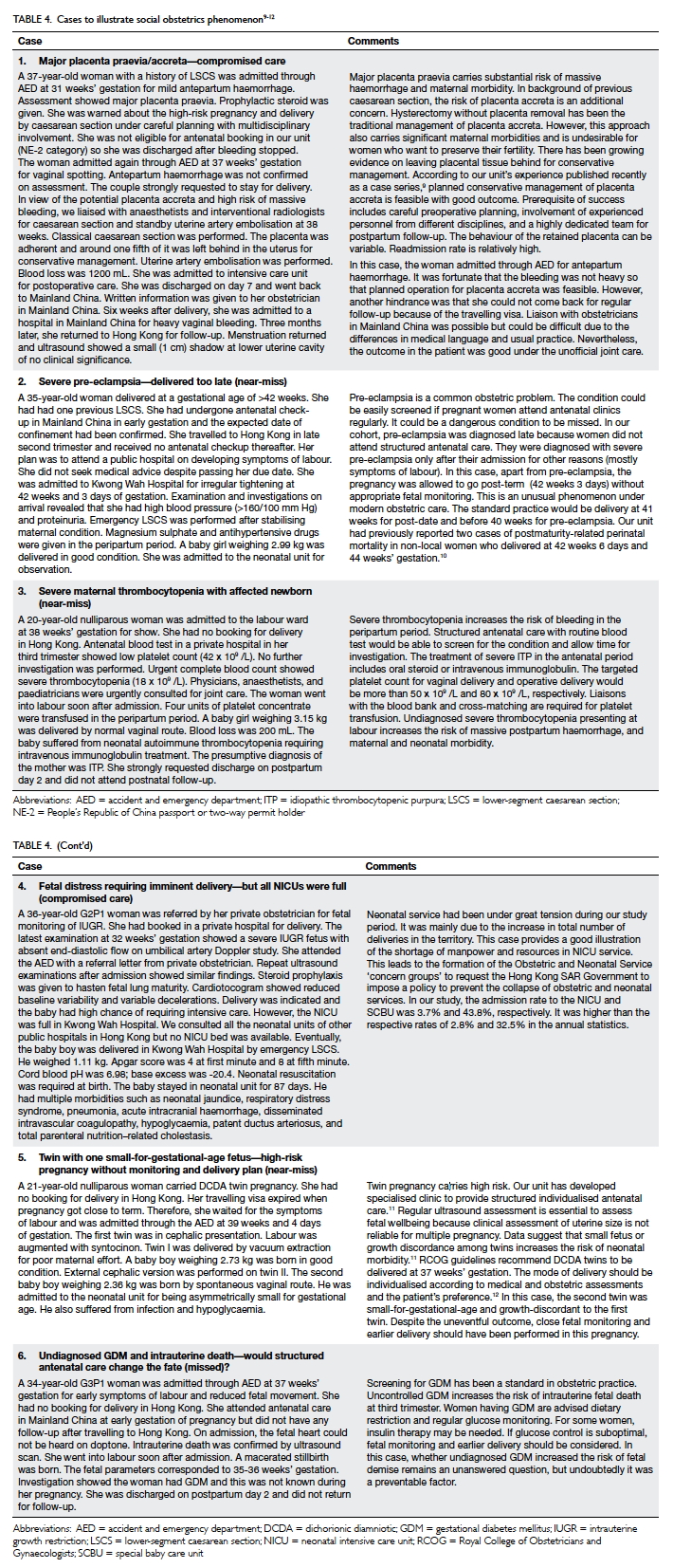

chosen six typical cases for illustrating this issue (Table

49 10 11 12).

Over the years, two local studies have been

published on the pregnancy outcomes of non-local expectant mothers

delivering in public hospitals in Hong Kong.6 7 Yuk

and Wong6 from Princess

Margaret Hospital conducted a study between 2004 and 2006 when the

HA launched the first obstetric package to the non-local women in

2005. During that period, around 35% of deliveries in Princess

Margaret Hospital were attributed to non-local Chinese women. The

proportion increased significantly from 27% in 2004 to 43% in

2006. Compared with local Chinese women, the NEPs were younger, of

lower parity, and had fewer pre-existing medical problems.

However, they had higher chances of unplanned vaginal breech

deliveries, severe hypertensive disease in pregnancy,

pre-eclampsia, delivering before arrival to hospital, and giving

birth post-term (≥42 weeks). Neonatal complications including

preterm birth, stillbirth, and neonatal death were also more

frequent among the NEP women. In fact, the first obstetric package

was proposed mainly to charge the NEPs for delivery service

expenses; it did not cover the antenatal service. This resulted in

many of them coming to the hospital only for giving birth. Many of

them came at the ‘last-minute’ to reduce the length of hospital

stay due to financial concerns. This created a heavy burden on the

public obstetric services and increased the risk of adverse

pregnancy outcomes.

The second obstetric package in 2007

encouraged the NEP mothers to receive proper antenatal checkup.

Lam7 from Tuen Mun Hospital

conducted a study from 2006 to 2008 investigating the impact of

the package on public obstetric services and pregnancy outcomes.

It was observed that the number of NEP deliveries decreased from

1868 to 1398 per year. The number of non-booked admissions through

AED reduced. The rate of post-term pregnancies dropped from 3.2%

to 1.8%. The reason for fewer deliveries was a shift of patients

to private obstetric services after setting the quota and raising

the cost. Nevertheless, this obstetric package did not improve the

admission behaviour and pregnancy outcomes.

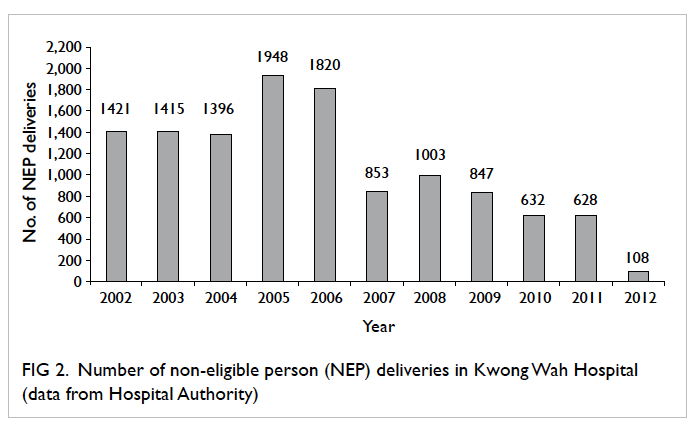

Thanks to our HA and the Hong Kong SAR

Government’s policy of stopping NEP bookings altogether in HA

Obstetric Units, the number of NEP deliveries during our study

period (2011-2012) was significantly reduced and limited to

non-booked cases admitted through AED (Fig 2). We observed that reduction in

‘quantity’ did not improve the ‘quality’ of care in this group of

women. The admission pattern and pregnancy outcomes remained

similar to those in previous local studies. We also observed that,

although some women had prior ‘booking’ in other HA or private

hospitals, their pregnancy outcomes were no better than the ‘no

booking’ group (Table 3). One possible reason for this

could be that their travelling permit hindered them from receiving

the ‘standard’ antenatal care. It was difficult to measure the

quality of the obstetric care received by the ‘booked group’

because of its heterogeneity. We have used case examples to

illustrate how the common obstetric conditions could be

‘near-miss’ conditions or standard obstetric service could be

compromised under this social obstetrics phenomenon. We foresee

that the third obstetrics package introduced in 2012 is unlikely

to make a significant improvement in pregnancy outcomes unless the

NEP women attend a structured antenatal care like the local

mothers do.

Figure 2. Number of non-eligible person (NEP) deliveries in Kwong Wah Hospital (data from Hospital Authority)

In our study, we compared the pregnancy

outcomes of our NEP cohort admitted through A&E (n=219) with

the general pregnant population from our annual statistics

(n=5862). This might introduce a pre-selection bias. Our NEP

cohort was also limited by its relatively small number. In the

study by Yuk and Wong,6 the

pregnancy outcomes of the NEP cohort (n=4657) were compared with

those of the eligible-person cohort (n=8655) from 2004 to 2006. In

the study by Lam,7 the

pregnancy outcomes of two NEP cohorts (n=1868 in 2006/2007 vs

n=1398 in 2007/2008) were compared.

Conclusion

Non-local expectant mothers delivering

babies in Hong Kong has become a classic social obstetrics

phenomenon. There is nothing wrong with these mothers who would

like to have their children to be born in Hong Kong and become

permanent residents of Hong Kong. Not long ago, Hong Kong mothers

wanted to give birth in the US or Canada so that their children

could become citizens of those countries. The problem in Hong Kong

is the large volume of pregnancies which has exceeded our

obstetric and neonatal capacities, thus affecting the health care

of our local pregnant mothers and neonates. Although our

Government now prohibits NEP bookings in both public (for NE-2 and

NE-3 categories) and private (for NE-2 category) hospitals,

non-local expectant mothers continue to admit themselves through

AED for deliveries. Health care professionals should continue to

be prepared for managing these potential near-miss clinical

situations arising from this social obstetrics phenomenon. We hope

this paper serves as one of the historical records in literature

for this social obstetrics phenomenon in the recent obstetric

history of Hong Kong.

References

1. Leung WC. Social

obstetrics—non-local expectant mothers delivering babies in Hong

Kong. The Hong Kong Medical Diary 2009;14:13-4.

2. Leung WC, Lau WL. Cross-border

families: transgression and dialogue [in Chinese]. Hong Kong: Red

Publishing; 2008: 55-9.

3. Leung WC. Social obstetrics

(cross-border pregnant women) [in Chinese]. Chiu MC, editor.

Children, medicine, law: a comparative study of Greater China.

Hong Kong: Roundtable Publishing; 2012: 40-8.

4. Au Yeung SK. Impact of

non-eligible person deliveries in obstetric service in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong J Gynaecol Obstet Midwifery 2006;6:41-4.

5. Leung TY, Lao T. Influx of

mainland expectant mothers: a blessing or a curse? Hong Kong J

Gynaecol Obstet Midwifery 2009;11:9-10.

6. Yuk JY, Wong S. Obstetrical

outcomes among non-local Chinese pregnant women in Hong Kong. Hong

Kong J Gynaecol Obstet Midwifery 2009;9:9-15.

7. Lam KD. Is the new obstetrics

package for non-local pregnant women making a change? Hong Kong J

Gynaecol Obstet Midwifery 2010;10:62-8.

8. Kwan WY, So CH, Chan WP, Leung

WC, Chow KM. Re-emergence of late presentations of fetal

haemoglobin Bart's disease in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J

2011;17:434-40.

9. Lo TK, Yung WK, Lau WL, Law B,

Lau S, Leung WC. Planned conservative management of placenta

accreta—experience of a regional general hospital. J Matern Fetal

Neonatal Med 2014;27:291-6. CrossRef

10. Yung C, Liu K, Lau WL, Lam H,

Leung WC, Chin R. Two cases of postmaturity-related perinatal

mortality in non-local expectant mothers. Hong Kong Med J

2007;13:231-3.

11. Yung WK, Liu AL, Lai SF, et

al. A specialised twin pregnancy clinic in a public hospital. Hong

Kong J Gynaecol Obstet Midwifery 2012;12:21-32.

12. Liu AL, Yung WK, Lai SF, et

al. Factors influencing the mode of delivery and associated

pregnancy outcomes for twins: a retrospective cohort study in a

public hospital. Hong Kong Med J 2012;18:99-107.