Hong Kong Med J 2014;20:94–101 | Number 2, April 2014 | Epub 14 Mar 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134027

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Current practices, attitudes, and perceived barriers for treating smokers by Hong Kong dentists

Kenneth WK Li, BDS1; David VK Chao, FRCGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)2

1 Tai Po Wong Siu Ching Government Dental Clinic, 1 Po Wu Lane, Tai Po,

Hong Kong

2 Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care, United

Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KWK Li (wkk_li@yahoo.com.hk)

Abstract

Objectives: To assess the attitudes of dentists

towards smoking cessation advice, as well as to

investigate their current practice and perceived

barriers to giving such advice and the relationships

among their peers regarding such activity.

Design: Cross-sectional survey.

Setting: Hong Kong.

Participants: Self-reporting questionnaires were

mailed to 330 dentists in Hong Kong by systematic

sampling. Information on their attitudes, practices,

and perceived barriers towards smoking cessation

advice and relevant background information was

collected.

Results: A total of 218 questionnaires were returned

(response rate, 66%). The majority (97%) reported

that they would enquire into every patient’s smoking

status, yet only around half of them did so routinely.

Most (95%) of the dentists who always enquired

about smoking status would actually offer smoking

cessation advice to their patients. Multiple logistic

regression of the results revealed that government

dentists (odds ratio=2.7; 95% confidence interval,

1.4-5.1), those who received training in smoking

cessation advice (2.5; 1.2-5.1), and those aged over

40 years (1.9; 1.0-3.4) were significantly more likely to enquire about smoking status. In most practices

(93%), smoking cessation advice was offered

by the dentists themselves rather than by other

team members. “Lack of training”, “unlikely to be

successful”, and “possibility of losing patients” were

the three barriers regarded as “very important” by

dentists.

Conclusions: Dentists in Hong Kong generally had

positive attitudes towards smoking cessation advice.

The dental team is in a very good position to help

smokers quit. However, training and guidelines

designed specifically for dental teams are paramount

to overcome barriers in delivering smoking cessation

advice by dental professionals.

New knowledge added by this

study

- The information gathered generally revealed a positive attitude towards delivering smoking cessation advice to smokers. However, lack of training and guidelines prevented dentists from implementing such advice in practice.

- This study raises the awareness of dentists about delivering smoking cessation advice to patients in their daily practice.

- There is a need of specific guidelines for dentists to achieve this goal.

- Practical training on such activity should be encouraged and included in both the undergraduate and postgraduate training of dentists.

Introduction

Tobacco smoking is one of the most significant public

health problems worldwide. The adverse effects of

smoking on health are well known.1 According to

the World Health Organization (WHO), the annual

death toll could rise to more than eight million by

2030, unless urgent action is taken against smoking.2

In Hong Kong, 11.1% of the population aged 15 years or above are daily smokers. Men are the

high-risk group and have a 22% prevalence of being

smokers, which is much higher than in women

(4%).3 The situation is particularly alarming, as the

smoking population is becoming younger.3 Smoking

contributes a large public health and medical burden

to society.

The Hong Kong SAR Government has implemented numerous policies and enacted

legislation on many occasions to combat tobacco

smoking. Such action has entailed raising tobacco

tax, making amendments to the existing Smoking

(Public Health) Ordinance to prohibit smoking in

public places, restricting the sale of tobacco products

and tobacco advertising. While strategies such as

taxation and prohibition of advertising are proven

to be effective, one effective strategy that should

not be ignored is “smoking cessation advice” (SCA)

delivered by health care professionals.

Smoking tobacco has been identified as

an important cause of various oral diseases and

pathologies. It is one of the most important factors

predisposing to pre-cancerous lesions and cancer of

the oral cavity, the reported pooled cancer risk being

3.4-fold higher than in non-smokers.4 It also increases

the risk of periodontal diseases,5 complications after

extractions,6 and increased rates of implant failures.7

Cross-sectional studies show that smokers have

more tooth loss.8 Other easily recognised effects

include staining of teeth,9 dental restorations, and

prosthesis10 as well as alteration of taste perception11

and halitosis.12 All these have detrimental effects

on the quality of life of smokers because of reduced

chewing efficiency, poor aesthetics, and poor self-esteem.13

The benefits of smoking cessation are

substantial. Evidence shows that smoking

counselling given by dental professions can be

effective and comparable to that offered by other

primary care professionals.14 15 16 Around a quarter of

the population have regular dental checkups and

53% have their teeth checked every 1 or 2 years.17 In

their daily practice, dental professionals have access

to a large patient population, including smokers.

Besides, the detrimental effects of smoking on the

oral cavity can be readily demonstrated directly and

thus easily appreciated by patients; this acts as a

strong motivator to quit smoking.16 Moreover, dental

treatments entailing multiple visits provide good

opportunities to motivate, reinforce, and support

smoking cessation. Thus, dental professionals

are in an excellent position for delivering advice

and counselling to smokers. Notably, counselling

by dentists has been reported to achieve an 8.6%

cessation rate after 1 year, and over 16% when also

coupled with nicotine replacement therapies.18

Despite these observations, delivery of SCA by

dentists remains less than satisfactory.19 20 21 22 According

to the literature, the reported barriers to such activity

include lack of time, resources, remuneration,

training, and fear of damaging dentist-patient

rapport.23

In Hong Kong, a study conducted in 2006

showed that more than half of all medical doctors did

not have adequate knowledge (53%) or favourable

attitudes (55%) towards smoking cessation.24 Slightly over 40% lacked confidence in delivery of SCA.

Although 77% of them obtained information on the

smoking status of their patients, only 29% advised

them to quit smoking, reflecting a low involvement

of medical doctors in the promotion of smoking

cessation.24

Local published data on the dentists’ attitudes,

practices, and barriers to delivering SCA to patients

are limited, except for one study by Lu et al.25 The

rationale of the present study was to collect data

from local dentists, and compare local results with

those gleaned from international studies.

The objectives of the present study were: (1) to

assess the attitudes of dentists towards SCA; (2) to

investigate the current practice of dentists in respect

of SCA; (3) to examine the perceived barriers to

offering SCA; and (4) to seek possible relationships

between the characteristics of dentists and their

SCA activity.

Methods

A 17-item structured, self-administered and

validated questionnaire developed by Stacey et

al26 in 2006 in the UK was adopted as the survey

instrument. The questionnaire consisted of three

main parts: (1) smoking cessation views and

activities of the dental team; (2) perceived barriers to giving SCA; and (3) perception of the importance

of the smoking cessation role of the dental team and

general medical practitioners. It was pilot-tested

with a small convenience sample (n=20) of dentists.

The target population consisted of 2026

general dentists registered with the Hong Kong

Dental Council, whose correspondence addresses

are available on a website27 that is open to the general

public. The inclusion criterion was any dentist who

was currently having a dental practice in Hong Kong

with a valid address at the time of this survey. A

systematic sample (every 6th dentists on the list) was

drawn from the 2026 registered general dentists in

Hong Kong, so as to yield the desired sample size. A

sample size of 324 subjects was calculated as needed

based on a 5% margin of error (type I error), and

95% confidence level, assuming 50% response after

distribution. Thus, 330 questionnaires were mailed

in January 2012 with stamped self-addressed reply

envelopes. Other means of reply allowed were by fax

or by online completion of the questionnaires via a

designated website. Another follow-up round of 330

questionnaires was sent to these dentists again 3

weeks after the first mailing.

Data analysis

A pilot study was carried out with a convenience

sample (n=20) to ensure the face validity of the

questionnaire. Test-retest reliability test was also

performed using these 20 subjects who were asked to

complete the questionnaire a second time (2 weeks

later). The questionnaire was viewed by three experts

in dental public health to ensure its suitability for the

present study.

All data were analysed with the Statistical

Package for the Social Sciences (Windows version

19.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US). Frequency

distributions were generated to illustrate the

demographic data, their attitudes, practices,

and perceived barriers in SCA. To examine any

relationships between demographic variables and

outcomes, unconditional logistic regression analysis

was performed with each demographic variable

and the outcome variables (attitudes, practices,

perceived barriers). Multiple logistic regression was

then performed for variables that yielded a P value

of <0.25 in the individual analysis. The final model

contained those statistically significant variables,

using a stepwise-forward Wald logistic regression.

The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

Response rate and demographic backgrounds

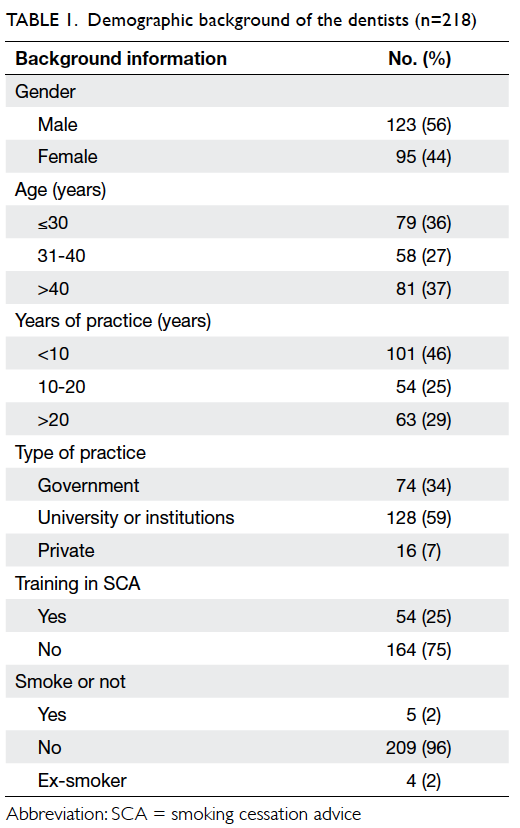

From the 330 selected dentists, 223 questionnaires

were returned (163 by mail, 39 by fax, 21 online), of

which five were incomplete. Thus, 218 questionnaires

were valid for analysis, yielding a response rate of 66%. Alarmingly, less than one fourth of the dentists

had received training in SCA. Only 16% of them had

received such training during their undergraduate

training and only 12% during postgraduate training.

Moreover, only approximately 60% of the dentists

claimed that they knew the contact of relevant

supporting agencies for SCA. Table 1 shows the

background of these dentists.

Current practices on smoking cessation

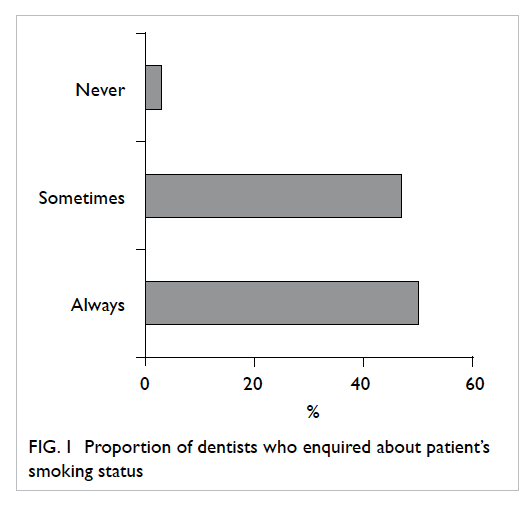

Nearly 97% of the dentists claimed that they would

enquire about their patients’ smoking status, yet

only around half of them would always do so as a

routine (Fig 1). About 97% would enquire about

smoking status whenever a patient presented with

oral diseases related to smoking (eg periodontal

disease and leukoplakia). The percentage of routine

enquiries about smoking status when patients

presented with oral white lesion (a symptom of oral

pre-cancer) was slightly higher (73%) than those

presented with periodontal disease (66%).

For dentists who would not routinely enquire

about the smoking status, around half (53%) would

always do so when patients presented with an oral

white lesion, and around 40% would do so when the

latter presented with periodontal disease.

For dentists who would always enquire about

smoking status, 95% claimed they actually offered

SCA. The majority of the dental practices (93%)

entailed SCA offered by the dentists themselves,

only 16% had dental nurses/hygienists who offered such advice and only 3% had practice managers/receptionists who did so.

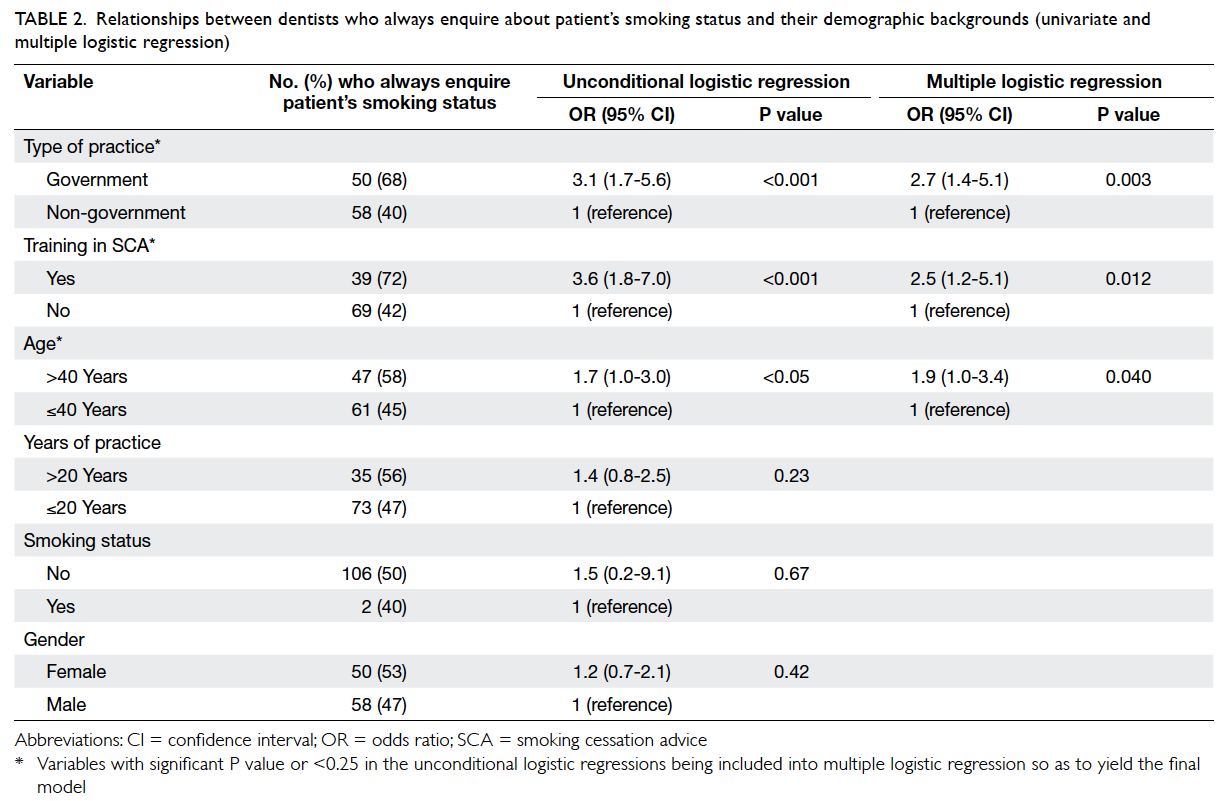

After adjustments and exclusion of non-significant

variables in the unconditional logistic

regressions, only three variables were retained in

the final model and were found to be statistically

significant. These were the type of practice, receipt

of training in SCA, and age. Government dentists,

those who had received training in SCA, and those

aged over 40 years were more likely to always enquire

about their patients’ smoking status (outcome

variable of the model, P<0.05; Table 2).

Table 2. Relationships between dentists who always enquire about patient’s smoking status and their demographic backgrounds (univariate and multiple logistic regression)

Trained dentists were more likely to always

enquire about smoking when patients presented

with periodontal disease than non-trained dentists,

the respective odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence

interval (CI) being 3.3 and 1.5-7.2. Government

dentists were also more likely to enquire about

smoking when patients presented with a white oral

lesion (OR=2.9; 95% CI, 1.4-6.1).

Similar results prevailed with respect to

actually offering SCA to patients. Government

dentists offered such advice more often than non-government

dentists according to the logistic

regression analysis (OR=8.3; 95% CI, 1.1-64.4).

Moreover, government dentists were more likely to know how to contact supporting agencies

(OR=2.3; 95% CI, 1.1-4.6) than non-government

counterparts, and trained dentists were more

likely to know how to contact supporting agencies

(OR=14.3; 95% CI, 4.2-48.5) than those non-trained.

Attitudes and perceptions of dentists on the

role of delivering smoking cessation advice

A high proportion (89%) of dentists agreed or strongly

agreed that the dental team has an important role

in delivering SCA to patients; the percentage who

agreed or strongly agreed that medical doctors had

an important role was slightly higher (93%).

Trained dentists were 8.5 times more likely

to think that it was imperative for dental teams to

offer SCA (P<0.05). Almost all (98%) of those who

received training thought that dentists should offer

SCA, which was more than that for those who did

not have such training (86%; P=0.014).

When dentists were asked who should offer

SCA in the team, most (approximately 90%) claimed

that they should be responsible, whilst 41% thought

that nurses should also be involved, and 47% felt

that hygienists too should be involved. However,

only 16% of such personnel were actively involved

in offering SCA; the percentages were even lower for

receptionists (3%) and practice managers (1%).

Perceived barriers to delivering smoking

cessation advice by dentists

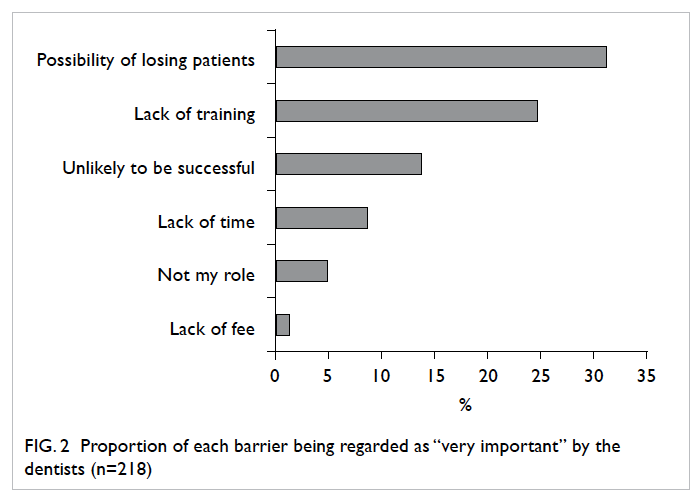

Among the potential barriers listed in the

questionnaire, the most important one identified by

the dentists was the “possibility of losing patients”

(31%), followed by the “lack of training” (25%) and

the “unlikely to be successful” (14%). On the other

hand, the “lack of time”, the “lack of fee”, and the

“not perceived as my role” were not regarded as important (Fig 2).

Discussion

This study gathered information on the current

attitudes, practices, and perceived barriers among

dentists in delivering SCA to Hong Kong patients,

which could have implications for the development

of training programmes and provide directions for

future research.

Knowledge and attitudes towards smoking

cessation advice

The present study showed that Hong Kong dentists

generally had positive attitudes and knowledge

about SCA, and recognised the adverse effects of

smoking on oral health, as reflected by the high

percentages for enquiry about a patient’s smoking

status. Moreover, nearly 90% expressed positive

attitudes towards SCA, in that they agreed it had an

important role to play.

Training and guidelines are important but

inadequate

Government dentists and dentists who received

training were significantly more likely (approximately

3 times) to routinely enquire about a patient’s

smoking status than other dentists. Trained dentists

were also approximately 14 times more likely to know

how to contact local supporting agencies, and more

than 8 times as likely to offer SCA to the patients.

They also perceived their role in offering SCA as

very important and were more actively involved

than other team members in its delivery. These

results were similar to those for Hong Kong medical

doctors,24 as well as findings of other international

and local studies.20 21 22 25

This study reflects the importance of

training and guidelines, although these were not

widely available. Only a small proportion (16%)

of dentists received training in SCA during their

undergraduate studies. Notably, for local students

the limited practical training in essential techniques

for delivering SCA to patients was similar to the

situation in the United States and Europe.28 29 Research has

shown that to increase the effectiveness of SCA,

education is needed to expand both didactic

knowledge and clinical competencies to help patients

quit smoking.30 Evidence also suggests that training

should be provided early and continued throughout

subsequent courses.31 Inclusion of both theoretical

and practical training (counselling skills, problem-solving

strategies) should be considered in future

undergraduate curricula. Moreover, continuing

professional education programmes focusing on

hands-on SCA techniques could help dentists

acquire better knowledge and more up-to-date

techniques. According to the results, the continuing education programmes should be directed towards

younger and non-government dentists.

The Department of Health has guidelines

on SCA for the government dental officers, which

includes annual updating of the patient’s smoking

status, provision of SCA, and obtaining patient

consent for referral to Tobacco Control Office when

needed. This may be one reason government dentists

were more likely to enquire about a patient’s smoking

status, offer SCA, and confirm the importance of

relevant guidelines. As in other countries, many

dentists are not familiar with guidelines like the “5A

approach”.32 Evidence suggests that dentists familiar

with guidelines are more likely to engage in SCA.33

Local information and guidelines on SCA are mostly

unclear, as they were not being designed specifically

for dentists and may not be readily accessible to

them.34 Not surprisingly, only approximately 60%

of the dentists knew how to contact supporting

agencies. Thus, clear, evidence-based, and easily

accessible guidelines designed for the dental

profession should be developed to facilitate the

effective delivery of SCA by dental professionals.

Recently, a WHO Collaborating Centre for

Smoking Cessation and Treatment of Tobacco

Dependence was set up by Department of Health. It

aims to provide evidence-based smoking cessation

training for health care personnel. It also aims

to develop, test, and evaluate models of smoking

cessation to support WHO’s initiatives on assistance

in the dissemination of relevant information on

smoking cessation. Hopefully therefore, the dental

profession will have more opportunities to receive

training in SCA in the near future.35

Barriers

Despite their apparently positive attitudes to SCA,

only around half of the dentists always enquired

about each patient’s smoking status and, if indicated,

offered SCA. These findings are consistent with

those from Australia36 and for Hong Kong medical

doctors.24 The difference in the beliefs and the

actual practice of dentists suggest barriers to

implementation. In the present study, “lack of

training”, “possibility of losing patients”, and “unlikely

to be successful” were regarded as important barriers

by the dentists, and were similar to those reported in

the UK26 and Malaysia.20 They suggest that dentists

lack confidence in delivering SCA and reinforce the

importance of adequate training. Dentists worry that

by offering SCA, they might damage relationships

with their patients. However, in reality, research

indicates that over half of the patients expect their

dentists to discuss issues related to smoking.37 Also,

such discussion could cultivate rapport between the

dentists and the patients. Thus, actually delivering

SCA could be very cost-effective in terms of gaining

patient trust. To encourage involvement of dentists in delivering SCA, efforts should be directed at

reducing the above-mentioned barriers (provision

of adequate training, informing the dentists about

current evidence, reducing their worries about

damaging relationships with patients).

Team approach

In this study, over 40% of the dentists expressed that

other personnel in their teams (nurses, hygienists)

should be involved in delivering SCA, though the

percentages were lower than those in the UK.26 Thus,

dentists generally recognised the importance of the

team approach to delivering SCA, and the literature

indicates that such team members (including

administrative staff) are in a good position to do

so.18 38 This is especially true for the hygienists, who

are responsible for managing periodontal diseases

that are smoking-related and require multiple visits,

and therefore offer excellent opportunities to deliver

SCA.39 40

The team approach should be encouraged, and

as team leader, the dentist has overall responsibility

and should actively involve other staff.41 In order to

increase the effectiveness, training of the entire dental

office team could be considered.42 The proportion of

local dentists who thought practice managers and

receptionists should be involved was low compared

to that reported from the UK.26 Variations in dental

clinic organisation in different countries may be part

of the reason; for example, locally it is not common

to involve dental practice managers in patient care.

Comparison with other studies

As mentioned previously, various aspects of our

results were generally comparable to those of other

studies. The response rate in the present study

was just under 70%, which was higher than 60%

reported from the UK,26 and 55% reported from

Malaysia,20 as well as 19% reported for Hong Kong

medical doctors24 and 50% in another study on

Hong Kong dentists.25 Our higher questionnaire

response rate could be because the questions were

simple, straightforward, and not time-consuming.

Notably, the locally developed questionnaire used by

Lu et al25 (on Hong Kong dentists) gathered more

detailed information than we did.

Limitations

The relatively low response rate in our study may

limit the generalisability of the results, and our

sample size was less than ideal. A full population

survey should be conducted if resources and time

permit. The tendency of respondents to provide

positive, favourable responses may be a source of

bias, resulting in an over-optimistic estimate of SCA

implementation. The characteristics of the non-respondents

were not known due to the anonymous nature of the questionnaire. The questionnaire was

comparatively simple, and did not address specific

aspects of knowledge on SCA, nor any specific

aspects of advice offered to patients. This limited the

scope of information being collected. Due to time

and resource limitations, other important personnel,

such as nurses and hygienists, were not surveyed.

Recommendations for future researches

A qualitative design could be considered to gain a

deeper understanding on the beliefs and barriers

to SCA with respect to the dental professions.

Thereafter an updated questionnaire could be

designed and validated, specifically for the local

setting. This could entail specific questions on

the knowledge of dentists regarding SCA and the

specific activities they and their teams undertake.

Further research could also focus on evaluating the

effectiveness of different smoking cessation training

programmes and practical approaches to SCA.

Conclusions

The present research showed that dentists in Hong

Kong generally have positive attitudes towards their

role in delivering SCA to patients. However, barriers

like the relative lack of training and guidelines,

the lack of confidence, and fear of damaging

relationships with patients may prevent them from

delivering the relevant advice. Local guidelines

specifically designed for the dental profession should

be developed and relevant resources made readily

accessible. More importantly, adequate practical

training programmes should be included in both

the undergraduate curriculum and continuing

education activities, especially for the private and

younger dentists.

References

1. World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2011: Warning about the dangers of tobacco. Geneva: WHO; 2011.

2. WHO key facts about tobacco. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs339/en. Accessed 29 Apr 2012.

3. Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong. General household survey and thematic household survey, 2011. Available from: http://www.census2011.gov.hk/en/index.html. Accessed Feb 2014.

4. Gandini S, Botteri E, Iodice S, et al. Tobacco smoking and cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 2008;122:155-64. CrossRef

5. Bergstrom J. Periodontitis and smoking: an evidence-based appraisal. J Evid Based Dent Pract 2006;6:33-41. CrossRef

6. Johnson NW, Bain CA. Tobacco and oral disease. EU-Working Group on Tobacco and Oral Health. Br Dent J 2000;189:200-6.

7. Reibel J. Tobacco and oral diseases. Update on the evidence, with recommendations. Med Princ Pract 2003;12 Suppl 1:22-32. CrossRef

8. Ylöstalo P, Sakki T, Laitinen J, Järvelin MR, Knuuttila M. The relation of tobacco smoking to tooth loss among young adults. Eur J Oral Sci 2004;112:121-6. CrossRef

9. Eriksen HM, Nordbo H. Extrinsic discoloration of teeth. J Clin Periodontol 1978;5:229-36. CrossRef

10. Asmuseen E, Hansen EK. Surface discoloration of restorative resins in relation to surface softening and oral hygiene. Scan J Dent Res 1986;94:174-7.

11. Pasquali B. Menstrual phase, history of smoking and taste discrimination in young women. Percept Mot Skills 1997;84:1243-6. CrossRef

12. Rosenberg M. Clinical assessment of bad breath: current concepts. J Am Dent Assoc 1996;127:475-82. CrossRef

13. Gerritsen AE, Allen PF, Witter DJ, Bronkhorst EM, Creugers NH. Tooth loss and oral health–related quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:126. CrossRef

14. Needleman IG, Binnie VI, Ainamo A, et al. Improving the effectiveness of tobacco use cessation (TUC). Int Dent J 2010;60:50-9.

15. John J. Tobacco smoking cessation counselling interventions delivered by dental professionals may be effective in helping tobacco users to quit. Evid Based Dent 2006;7:40-1. CrossRef

16. Warnakulasuriya S. Effectiveness of tobacco counseling in the dental office. J Dent Educ 2002;66:1079-87.

17. Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong. General household survey and thematic household survey, report no. 45. Available from: http://smokefree.hk/UserFiles/resources/smoking_risk_cessation/thematic_household_surveys/THS_45Report.pdf. Accessed Feb 2014.

18. Cohen SJ, Stookey GK, Katz BP, Drook CA, Christen AG. Helping smokers quit: a randomized controlled trial with private practice dentists. J Am Dent Assoc 1989;118:41-5.

19. Allard RH. Tobacco and oral health: attitudes and opinions of European dentists; a report of the EU working group on tobacco and oral health. Int Dent J 2000;50:99-102. CrossRef

20. Ibrahim H, Norkhafizah S. Attitudes and practices in smoking cessation counselling among dentists in Kelantan. Archives of Orofacial Sciences 2008;3:11-6.

21. Uti OG, Sofola OO. Smoking cessation counseling in dentistry: attitudes of Nigerian dentists and dental students. J Dent Educ 2010;75:406-12.

22. Victoroff KZ, Dankulich-Huryn T, Haque S. Attitudes of incoming dental students toward tobacco cessation promotion in the dental setting. J Dent Educ 2004;5:563-8.

23. Watt RG, McGlone P, Dykes J, Smith M. Barriers limiting dentists' active involvement in smoking cessation. Oral Health Prev Dent 2004;2:95-102.

24. Abdullah AS, Rahman AS, Suen CW, et al. Investigation of Hong Kong doctors' current knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, confidence and practices: implications for the treatment of tobacco dependency. J Chin Med Assoc 2006;69:461-71. CrossRef

25. Lu HX, Wong MC, Chan KF, et al. Perspectives of the dentists on smoking cessation in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Dent J 2011;8:79-86.

26. Stacey F, Heasman PA, Heasman L, Hepburn S, McCracken GI, Preshaw PM. Smoking cessation as a dental intervention—views of the profession. Br Dent J 2006;201:109-13. CrossRef

27. The Hong Kong Dental Council. Lists of Registered Dentists in Hong Kong, September 2011. DCHK website: http://www.dchk.org.hk/docs/List_of_Registered_Dentists_Local.pdf. Accessed 2 Jan 2012.

28. Geller AC, Powers CA. Teaching smoking cessation in U.S. medical schools: a long way to go. Virtual Mentor 2007;9:21-5. CrossRef

29. Raupach T, Shahab L, Baetzing S, et al. Medical students lack basic knowledge about smoking: findings from two European medical schools. Nicotine Tob Res 2009;11:92-8. CrossRef

30. Ramseier CA, Christen A, McGowan J, et al. Tobacco use prevention and cessation in dental and dental hygiene undergraduate education. Oral Health Prev Dent 2006;4:49-60.

31. Brown RL, Pfeifer JM, Gjerde CL, Seibert CS, Haq CL. Teaching patient-centered tobacco intervention to first-year medical students. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:534-9. CrossRef

32. Succar CT, Hardigan PC, Fleisher JM, Godel JH. Survey of tobacco control among Florida dentists. J Community Health 2011;36:211-8. CrossRef

33. Hu S, Pallonen U, McAlister AL, et al. Knowing how to help tobacco users. Dentists' familiarity and compliance with the clinical practice guideline. J Am Dent Assoc 2006;137:170-9. CrossRef

34. Tobacco Control Office, Department of Health, Hong Kong. Health promotion-tobacco control resources centre. Available from: http//www.tco.gov.hk/English/health/health_tcrc.html. Accessed 1 May 2012.

35. Hong Kong Council on Smoking and Health. News update—First WHO collaborating centre for smoking cessation officially launched in Hong Kong. COSH Website: http://smokefree.hk/en/content/web.do?page=news20120410. Accessed 4 May 2012.

36. Trotter L, Worcester P. Training for dentists in smoking cessation intervention. Aust Dent J 2003;48:183-9. CrossRef

37. Rikard-Bell G, Donnelly N, Ward J. Preventive dentistry: what do Australian patients endorse and recall of smoking cessation advice by their dentists? Br Dent J 2003;94:159-64. CrossRef

38. Pizzo G, Piscopo MR, Pizzo I, Giuliana G. Smoking cessation counselling and dental team [in Italian]. Ann Ig 2006;18:155-70.

39. Severson HH, Andres JA, Lichtenstein E, Gordon JS, Barckley MF. Using the hygiene visit to deliver a tobacco cessation program: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Am Dent Assoc 1998;129:993-9. CrossRef

40. Stevens VJ, Severson H, Lichtenstein E, Little SJ, Leben J. Making the most of a teachable moment: a smokeless-tobacco cessation intervention in the dental office. Am J Public Health 1995;85:231-5. CrossRef

41. Campbell HS, Sletten M, Petty T. Patient perceptions of tobacco cessation advice in dental offices. J Am Dent Assoc 1999;130:219-26. CrossRef

42. Wood GJ, Cecchini JJ, Nathason N, Hiroshige K. Office based training in tobacco cessation for dental professionals. J Am Dent Assoc 1997;128:216-24. CrossRef