Hong Kong Med J 2014;20:74–7 | Number 1, February 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj133780

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Middle cerebral artery infarction in a cancer patient: a fatal case of Trousseau’s syndrome

Peter YM Woo, MB, BS, MRCS (Edin)1;

Danny TM Chan, MB, ChB, FRCS (Edin)1;

Tom CY Cheung, MB, ChB, FRCR2;

XL Zhu, BMed (Jinan) FRCS (Edin)1;

WS Poon, MB, ChB (Glasg), FRCS (Edin)1

1 Division of Neurosurgery, Department of Surgery, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin,

New Territories, Hong Kong

2 Department of Imaging and Interventional Radiology, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin,

New Territories, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof WS Poon (wpoon@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Trousseau’s syndrome is defined as any unexplained

thrombotic event that precedes the diagnosis of an

occult visceral malignancy or appears concomitantly

with a tumour. This report describes a young,

previously healthy man diagnosed to have an acute

middle cerebral arterial ischaemic stroke and lower-limb

deep vein thrombosis, who subsequently

succumbed to pulmonary arterial embolism. During

the course of his illness, he was diagnosed to have

a malignant pleural effusion secondary to an occult

adenocarcinoma. This report highlights the need

for a high degree of suspicion for occult malignancy

and non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis in

young (<60 years old) ischaemic stroke patients

with no identifiable conventional cardiovascular

risks. In selected patients, transoesophageal

echocardiography is the diagnostic investigation

of choice, since transthoracic imaging is not sensitive. Screening tests for serum tumour markers

and prompt heparinisation of these patients are

suggested whenever ischaemic stroke secondary to

malignancy-induced systemic hypercoagulability is

suspected.

Case report

A 37-year-old Korean man, who was a non-smoker

and previously healthy, experienced a sudden-onset

right hemiparesis in April 2011. The patient was

travelling in Guangzhou, China and was hospitalised

within 4 hours of symptom onset. He was diagnosed

to have a left middle cerebral artery (MCA)

territory massive infarct based on plain computed

tomography (CT). Contrast-enhanced magnetic

resonance arteriography indicated a left proximal

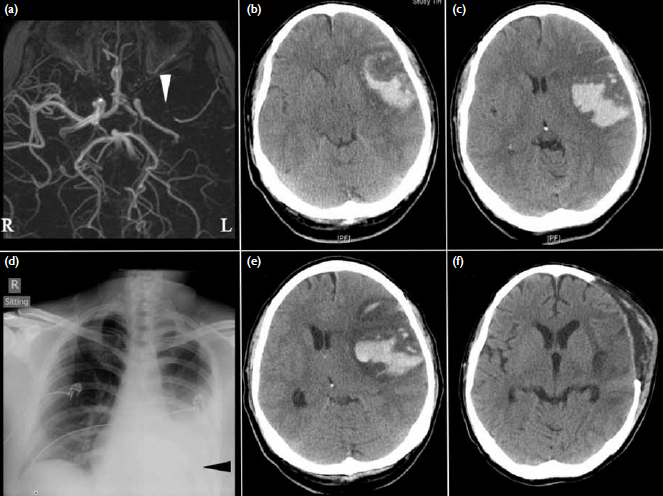

MCA occlusion (Fig a). The patient was treated

conservatively and neither thrombolytic therapy nor

operative management was given. Three days later,

he was transferred to Hong Kong.

Figure. (a) Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiograms on the day of symptom onset showing a left proximal middle cerebral artery (MCA) occlusion (white arrowhead). Brain computed tomography (CT) conducted 4 days later revealing haemorrhagic conversion of a left MCA region infarction with obliteration of (b) the basal cisterns and (c) midline shift. (d) Evidence of a left pleural effusion (black arrowhead) is present on the admission chest X-ray. (e) Deterioration in consciousness 8 days after symptom onset correlated with increased midline shift secondary to increased peri-haematomal oedema. (f) The 2-week postoperative CT showing satisfactory decompression and resolution of the intracerebral haematoma

On examination the patient had expressive

aphasia and right hemiplegia. He was able to obey

commands, had a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 11/15

(E4V1M6) and was afebrile. His blood pressure was

not high and his pulse was regular, nor were carotid

bruits or heart murmurs detected.

Repeat CT of the brain showed a massive

left MCA territory infarction with haemorrhagic

conversion and a chest X-ray revealed a left pleural

effusion (Figs 1b-d). An electrocardiogram (ECG)

showed no arrhythmias and initial blood test results

showed a raised white cell count of 15.4 x 109 /L

with neutrophilia. Other than that, the complete

blood count, fasting serum glucose, lipid profile,

and autoimmune markers were all within normal

limits. The patient was initially managed medically with close neurological observations. In view of the

neutrophilia, the patient was provisionally diagnosed

to have bacterial endocarditis with complicating

chest infection and parapneumonic pleural effusion.

An echocardiogram was arranged and empirical

intravenous antibiotics started.

Four days later, the patient became increasingly

drowsy and an emergency decompressive

craniectomy and duraplasty was performed (Figs 1e-f). The procedure was uneventful and the patient

was stabilised.

As for delineating the cause for the stroke, all

specimen culture results showed no evidence of an

underlying infection. Percutaneous aspiration of the

pleural effusion and pleural biopsy were performed.

The biopsy showed no evidence of malignancy, but

fluid cytology yielded adenocarcinoma cells. Serum

tumour markers, including carcinoembryonic

antigen and alpha-fetoprotein, were normal. The

patient developed sinus tachycardia with an ECG

showing a right heart strain pattern, before further

cardiological tests (positron emission tomography

and echocardiogram) could be performed. Blood for

troponin-T and D-dimer levels were also elevated.

The patient was subsequently diagnosed to have

bilateral lower-limb deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

extending from the external iliac vein to the popliteal

vein. Thoracic CT was consistent with pulmonary

embolism to the right lower lobe pulmonary arteries.

Subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin was started and an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter

was placed. The patient's condition continued

to deteriorate and he developed disseminated

intravascular coagulopathy and respiratory failure.

Progression of the pulmonary embolism was

suspected, but the patient was deemed unsuitable

for systemic thrombolysis due to his recent

neurosurgery. The patient succumbed 2 weeks

after the operation. A post-mortem examination

was arranged, but waived by the coroner upon the

family's request. The cause of death was pulmonary

embolism contributed by an occult malignancy.

Discussion

Ischaemic stroke is the second most frequent

neurological finding after brain metastases in post-mortem

studies of cancer patients.1 From an autopsy

study, cerebral infarction was observed in 15% of

3426 patients diagnosed with cancer, of whom half

were previously symptomatic.1 In a recent single-centre

retrospective review of 5106 patients admitted

for ischaemic stroke, 24 (0.47%) were diagnosed to

have an underlying malignancy. In this subgroup of patients, the mean age was relatively young (52

years) and there was a lower incidence of the typical

vascular risk factor profiles as noted in larger stroke

cohort studies.2

Trousseau first described the association between vascular thrombosis and cancer in his

monograph of a peculiar migratory thrombophlebitis

in 1865 and diagnosed the syndrome on himself

2 years later when he succumbed to gastric

adenocarcinoma.3 4 There are several definitions for

Trousseau's syndrome including "the occurrence

of thrombophlebitis migrans with visceral cancer"

and "spontaneous recurrent venous thromboses

and/or arterial emboli caused by non-bacterial

thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE) in a patient with

malignancy".4 But a prima facie definition should be

any "unexplained thrombotic event that precede[s]

the diagnosis of an occult visceral malignancy or

appear[s] concomitantly with the tumor".4

It is estimated that 15% of cancer patients will

suffer from a thromboembolic event during the

course of their illness and up to 50% have evidence

of venous thromboembolism on post-mortem

examination.5 The underlying pathophysiological

mechanisms can be broadly classified as either

due to the malignancy itself or as an iatrogenic

complication of oncological treatment such as

radiotherapy-induced arteriopathy. In turn, tumour-related

ischaemic cerebrovascular events can be

due to systemic hypercoagulability as part of a

paraneoplastic syndrome, tumour emboli secondary

to vessel infiltration, or contiguous compression of

an artery. For this patient the thoracic CT revealed no

evidence of infiltration of mediastinal great vessels or

a cardiac lesion, so the possibility of arterial tumour

emboli was unlikely. Brain magnetic resonance

imaging also did not show brain metastasis. The

fact that the patient developed extensive vascular

thrombosis with bilateral lower-limb DVT and

pulmonary embolism in spite of an IVC filter

suggests that the cause of the stroke may have been

due to malignancy-associated hypercoagulability.

The biological basis for systemic coagulopathy

in Trousseau's syndrome has yet to be defined.

It is thought to result from a complex interplay of

tumour cell secretion of procoagulants and the

host's blood vessels. When macrophages interact

with malignant cells, there is a release of cytokines

such as interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and tumour

necrosis factor that can lead to endothelial damage

and thrombogenesis on viable surfaces.6 Tumour

cells may also secrete tissue factor and cysteine

proteases with thromboplastin-like properties

that activate coagulation factors VII and X. Finally

mucin-producing adenocarcinomas can lead to

direct non-enzymatic activation of factor X.7 In

this state of hypercoagulability, the two commonest

underlying mechanisms for ischaemic stroke are

related to cardiogenic embolism from NBTE or

cerebral intravascular coagulation.8

Non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis

Up to half of patients with NBTE develop systemic emboli, most often to the cerebral vasculature and

result in stroke, but some emboli also end up in the

pulmonary, cardiac, and renal circulations.6 This

may have been the underlying cause for the patient's

massive MCA infarction and pulmonary embolism.

Formally known as marantic endocarditis, the

condition is characterised by sterile platelet and fibrin

rich thrombi that form on previously undamaged

heart valves.9 The incidence is largely unknown

but according to Graus et al's autopsy series,1 it

was noted in 1.6% of adult cancer patients. Often,

it is encountered in patients with advanced-stage

malignancies, in particular adenocarcinomas of the

lung or gastro-intestinal tract; as in this patient,

rarely NBTE can be a harbinger of occult cancer.8 10

Its pathogenesis is incompletely understood, but

is possibly due to cytokine-mediated inflammatory

valvular tissue injury that predisposes to thrombus

formation.6 For several reasons, NBTE is difficult

to diagnose. Thus, though aortic and mitral valves

are the most commonly affected, patients seldom

have detectable cardiac murmurs.6 11 Concomitantly,

immunocompromised patients can suffer from

infective endocarditis that confounds the diagnosis.

Finally, transthoracic echocardiography is not

sufficiently sensitive in detecting the smaller friable

valvular vegetations of NBTE.12 Careful selection

of patients for transoesophageal echocardiography,

the preferred diagnostic test, is claimed to be

preferable.6 Patients without end-stage malignancy,

acceptable performance status of 3 or less on the

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale and with

non-debilitating stroke are suitable candidates. For

this patient, the diagnosis of NBTE was inferred in

view of the negative culture and serology results and

failed response to systemic antibiotics.

Treatment is directed at the underlying

malignancy coupled with systemic anticoagulation.

Since patients often present with

metastatic disease, curative options are limited and

anticoagulation should be administered indefinitely,

since thromboembolic events tend to recur after

discontinuation.6 Unfractionated heparin, given

either intravenously or subcutaneously, has been

proven to be most effective.6 Alternatively, low-molecular-weight heparin could be considered, but

evidence about its utility is anecdotal. In contrast,

vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin are not

recommended, as recurrent thromboembolic events

are common and expose the patient to unnecessary

bleeding risks.6 13 The exact reason for warfarin

resistance is unknown, but it has been suggested

that thrombosis secondary to cytokine-induced

inflammation is preferentially mediated by non-vitamin-K–dependent coagulation factors.13

Cerebral intravascular coagulation

Cerebral intravascular coagulation is a post-mortem pathological diagnosis made when cardiac

valvulopathy is excluded. Originally described in

autopsy studies among patients with leukaemia

and breast cancer, this condition involves diffuse

fibrinous occlusions of small cerebral blood vessels

leading to micro-infarcts. Patients often present

with progressive encephalopathy and seldom

develop focal neurological deficits, although partial

seizures have been reported.14 No reliable laboratory

or radiological investigations are available to detect

this disorder. Patients are usually in their preterminal

state and management is often supportive.8

Conclusion

This patient suffered from a fatal manifestation of

Trousseau's syndrome. One should be cognisant

of the diagnosis of NBTE as a cause of ischaemic

stroke in any patient with a known or suspected

underlying malignancy. This is particularly true

if new heart murmurs are detected in a cancer

patient. Conversely, for a young patient (<60 years

old), ischaemic stroke with no overt vascular risk

factors should be considered for cancer screening. In

selected cases, transoesophageal echocardiography

appears to be the investigation of choice for NBTE.

Anticoagulation, preferably with unfractionated

heparin, should be administered as soon as possible

in ischaemic stroke patients whenever such an event

is a suspected consequence of an occult or overt

malignancy causing systemic hypercoagulability.

References

1. Graus F, Rogers LR, Posner JB. Cerebrovascular complications in patients with cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 1985;64:16-35. Crossref

2. Taccone FS, Jeangette SM, Blecic SA. First-ever stroke

as initial presentation of systemic cancer. J Stroke

Cerebrovasc Dis 2008;17:169-74. Crossref

3. Trousseau A. Lectures on clinical medicine, delivered at

the Hotel-Dieu, Paris. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lindsay &

Blakiston; 1865: 281-332.

4. Varki A. Trousseau's syndrome: multiple definitions and

multiple mechanisms. Blood 2007;110:1723-9. Crossref

5. Deitcher SR. Cancer and thrombosis: mechanisms and

treatment. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2003;16:21-31. Crossref

6. el-Shami K, Griffiths E, Streiff M. Nonbacterial thrombotic

endocarditis in cancer patients: pathogenesis, diagnosis,

and treatment. Oncologist 2007;12:518-23. Crossref

7. Bick RL. Cancer-associated thrombosis. N Engl J Med

2003;349:109-11. Crossref

8. Rogers LR. Cerebrovascular complications in cancer patients. Neurol Clin 2003;21:167-92. Crossref

9. Gross L, Friedberg CK. Nonbacterial thrombotic

endocarditis. Classification and general description. Arch

Intern Med (Chic) 1936;58:620-40. Crossref

10. Edoute Y, Haim N, Rinkevich D, Brenner B, Reisner

SA. Cardiac valvular vegetations in cancer patients: a

prospective echocardiographic study of 200 patients. Am

J Med 1997;102:252-8. Crossref

11. Rosen P, Armstrong D. Nonbacterial thrombotic

endocarditis in patients with malignant neoplastic

diseases. Am J Med 1973;54:23-9. Crossref

12. Lee RJ, Bartzokis T, Yeoh TK, Grogin HR, Choi D,

Schnittger I. Enhanced detection of intracardiac sources

of cerebral emboli by transesophageal echocardiography.

Stroke 1991;22:734-9. Crossref

13. Bell WR, Starksen NF, Tong S, Porterfield JK. Trousseau's

syndrome. Devastating coagulopathy in the absence of

heparin. Am J Med 1985;79:423-30. Crossref

14. Collins RC, Al-Mondhiry H, Chernik NL, Posner JB.

Neurologic manifestations of intravascular coagulation

in patients with cancer. A clinicopathologic analysis of 12

cases. Neurology 1975;25:795-806. Crossref