Hong Kong Med J 2014;20:70–3 | Number 1, February 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj133879

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Scrotal wall metastasis as the first

manifestation of primary gastric adenocarcinoma

ST Leung, MB, BS, FRCR1; CY

Chu, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)1;

Billy MH Lai, MB, BS, FRCR1;

Florence MF Cheung, FRCPath, FHKAM (Pathology)2;

Jennifer LS Khoo, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)1

1 Department of Radiology,

Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

2 Department of Clinical

Pathology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan,

Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr ST Leung (baryleung@hotmail.com)

Abstract

Metastases to the scrotal wall are very

rare, and being

the initial manifestation of occult primary tumours

is even rarer. We report on a patient presenting

with painless scrotal swelling, attributed to a solid

extra-testicular mass found on ultrasonography.

Subsequent investigations and surgical exploration

revealed it to be a scrotal wall metastasis from an

occult gastric primary. To our knowledge, this is

the first report of a scrotal wall metastasis from

gastric adenocarcinoma. The ensuing discussion and

literature review highlight the diagnostic challenges

posed by an extra-testicular scrotal metastasis from

an occult primary tumour.

Introduction

Metastases from gastric adenocarcinoma to

scrotal

structures are rare, most being intra-testicular. Extra-testicular

metastases are even rarer. It is extremely

rare for such a metastasis to be the first manifestation

of an occult primary tumour. Herein we report on a

patient who presented with a solid extra-testicular

mass, which was later confirmed to be a scrotal wall metastasis

from an occult gastric adenocarcinoma.

To our best knowledge, there has been no previous

report of a scrotal wall metastasis from gastric

adenocarcinoma.

Case report

A 66-year-old man, who enjoyed unremarkable

past

health, presented with a 2-week history of painless ‘right

testicular’ swelling in May 2011. Examination

yielded a 4-cm hard, irregular, and non-tender right

scrotal mass.

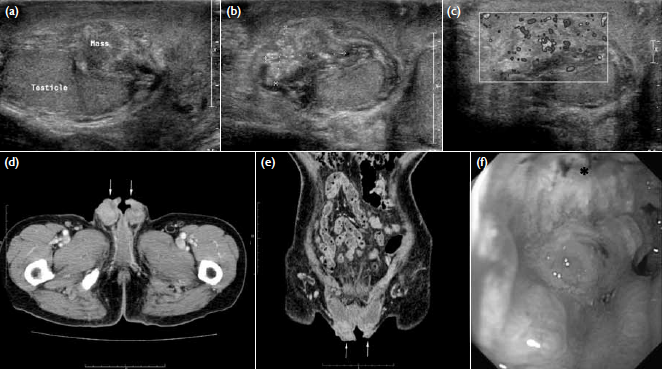

An urgent ultrasound revealed an 18 x 13 x

21-mm solid extra-testicular mass with heterogeneous

echogenicity in the right scrotum (Figs 1a-c), which

was separate from the normal-looking right testis.

Equivocal involvement of the right epididymis was

noted on the ultrasound at that time. Increased

vascularity of the mass lesion was noted on colour

Doppler study. A small right hydrocele was also

evident.

Figure 1. (a) Longitudinal and (b) transverse sonography of the right scrotum showing a solid extra-testicular mass separated from the normal-looking right testis. (c) Increased vascularity was evident on Doppler study. (d) Axial and (e) coronal computed tomographic images of the scrotum revealing bilateral scrotal soft-tissue thickening (arrows). (f) The oesophagogastroduodenoscopy reveals an irregular ulcerative tumour (*) over the lower part of gastric body

In view of a possible malignancy, the

patient

then underwent surgical scrotal exploration, which revealed a

markedly thickened scrotal wall. The dartos

muscles could not be well delineated and considered

a probable sight of invasion by tumour, though the

fat plane between the scrotal wall and the tunica was

preserved. The testes could be well separated from

the thickened scrotal wall.

A full-thickness scrotal wall incisional

biopsy

revealed diffuse infiltration of the subcutaneous

tissue and dartos muscle by aggregates and islands

of adenocarcinoma, more heavily on the right side.

Evidence of a desmoplastic reaction was noted. The

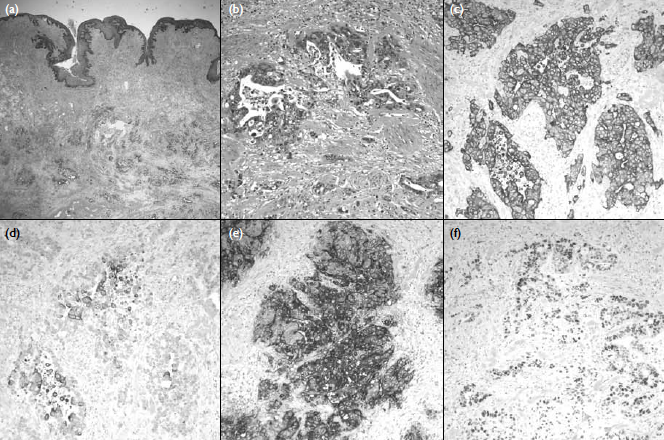

scrotal skin was unremarkable (Figs 2a-b).

Figure 2. Pathological examination showing that (a) the soft tissue underlying the scrotal skin was infiltrated by adenocarcinoma (H&E, x 20) and (b) malignant glands lined by pleomorphic cells seen in the dartos muscle (H&E, x 200). Immunohistochemical studies (x 200) showing (c) tumour cells positive for CK7, but (d) only focally positive for CK20, and (e) strongly positive for carcinoembryonic antigen and (f) partly positive for p53. The overall features favour a tumour from the upper gastro-intestinal or genital origin

Immunological studies showed that the

tumour

cells were positive for CK7, carcinoembryonic

antigen, p53, and CDX2; focally positive for CK20

and negative for prostate-specific antigen (Figs 2c-f).

These features favoured a tumour of the upper gastro-intestinal

or genital origin. Biopsies of the urethra

and urinary bladder from the same operation were

negative of malignancy.

Subsequent computed tomography

(CT) of the abdomen and pelvis to search for

any underlying malignancy showed bilateral

scrotal soft tissue thickening (Figs 1d-e), and

oesophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed a hard,

irregular, and circumferential ulcerative tumour over

the lower part of body of stomach (Fig 1f). Biopsy of this ulcerative tumour

revealed a poorly differentiated

adenocarcinoma.

Palliative chemotherapy with the XELOX

regimen (capecitabine plus oxaliplatin) was started.

The chemotherapy regimen was subsequently changed

to the FOLFOX regimen (folinic acid, fluorouracil,

and oxaliplatin) because of progression of the gastric

malignancy. He remained otherwise asymptomatic

10 months following the initial presentation, when

this report was submitted for publication.

Discussion

The scrotum is a musculocutaneous sac

composed

of two compartments, divided by a midline septum.

Each compartment contains a testis, epididymis,

spermatic cord, and associated fascial coverings.1

The scrotal wall is composed of pigmented skin,

subcutaneous tissue, and the closely related dartos

fascia and dartos muscle.

Metastases to scrotal structures are rare.

Among these, the testis is the most frequently

involved site. Less than 3% of testicular malignancies

are secondaries; the lung, prostate, and gastro-intestinal

tract are the most common primary sites.2

3

Metastases to extra-testicular scrotal structures

such as the epididymis, spermatic cord, and scrotal

wall are even rarer. Metastases account for 8.1% of

malignancies in the epididymis and spermatic cord,3 4

mostly reported as single case reports.3

Metastasis to the scrotal wall involving

the

subcutaneous tissue and dartos muscle with normal

scrotal skin (as in our patient) is extremely rare. A

previous review could only identify sporadic cases

of scrotal wall metastases; the primaries being from

malignant melanoma, anal carcinoma, and lung

carcinoma.5 To our best

knowledge, no scrotal wall

metastasis from gastric adenocarcinoma has ever

been reported in the literature. On the other hand,

cutaneous metastases involving the scrotal skin alone

are relatively more common. In contrast to scrotal

wall metastases which present as a scrotal swelling,

scrotal skin metastases present as cutaneous polypoid

lesions, ulcers, or papules.6

7 8

Several pathways by which primary tumours

metastasise to the scrotal structures have been

proposed. They include retrograde venous

embolism, retrograde lymphatic extension, arterial

embolism, direct invasion along the testicular cord,

and transperitoneal seeding through a congenital

hydrocele.9 Although the

exact pathway of the

metastasis in our patient is not clear, absence of

intra-abdominal, pelvic lymphadenopathy, and

testicular cord thickening all favour embolism or

transperitoneal seeding as the route.

Clinically, a scrotal wall metastasis

usually

presents as a painless scrotal swelling with normal

overlying skin, with a firm-to-hard mass being evident

on physical examination. Ultrasonography usually reveals a solid

extra-testicular mass, that is mostly

hypoechoic but can have variable echogenicity.2

Previously described sonographic features of a scrotal

wall metastasis from a lung primary also entailed

increased peripheral vascularity and poor delineation

with the epididymis,2 in

which the features were also

observed in our patient.

Ultrasonography is usually the first

imaging

modality for evaluating patients presenting with

scrotal swelling. Its high spatial resolution provides

nearly 100% sensitivity in identifying a scrotal mass

and a 98 to 100% sensitivity in differentiating intra-testicular

versus extra-testicular lesions.1

The two

most important factors to consider during evaluation

of a scrotal mass are whether it is intra- or extra-testicular

in location, and whether it is cystic or solid

in nature.1 This is because

more than 95% intra-testicular

masses are malignant while most that are

extra-testicular are benign.10

Most extra-testicular masses are cystic and

almost all are benign.1

Solid extra-testicular masses

are uncommon and 97% of them are also benign.1 11

Among these solid extra-testicular masses, lipoma

and adenomatoid tumours are most frequently

encountered, and account for about 45% and 33% of

all extra-testicular masses, respectively.11

Malignancies account for the remaining 3%

of

extra-testicular masses. It was estimated that 8.1%

of malignancies in the epididymis and spermatic

cord are due to metastases.3

4 Rhabdomyosarcoma

is the most common primary malignant tumour,

accounting for 40% of all malignant extra-testicular

tumours and are most common in infants and

children.11 In adults,

examples of primary malignant

tumours include leiomyosarcoma, liposarcoma,

fibrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, and

primary adenocarcinoma of epididymis.5

Secondary extra-testicular malignant

tumours

usually occur against a background of known

advanced malignancy. Common primary sites

include prostate, kidney, gastro-intestinal tract,

and pancreas.11 Epididymis

and spermatic cord

are the usual sites of involvement, while scrotal

wall metastases are extremely rare. Only sporadic

case reports can be identified in the literature for

metastases to the scrotal wall (from melanoma, anal

carcinoma, and lung carcinoma).2

12

Lesion diameter, volume, and presence of

vascularity on Doppler ultrasonography assist

differentiation of malignant from benign lesions.13

Multifocal lesions and heterogeneity have also been

suggested as supporting metastatic disease.14 15

However, in most instances, considerable overlap

in sonographic appearances of many solid extra-testicular

masses preclude a specific diagnosis.1

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful

in

characterising certain extra-testicular lesions such

as lipoma, haematoma, and fibrous pseudotumour. Enhancement

patterns in gadolinium-enhanced

MRIs are also useful in differentiating malignant

from benign lesions. In such cases, MRI findings may

obviate the need for surgery or change the surgical

approach.14

In patients without a known history of

malignancy such as ours, diagnosis of an extra-testicular

metastasis on the initial ultrasound is

difficult. The sonographic differential diagnosis

includes other extra-testicular benign and malignant

tumours. Clinical correlation is essential to enable

better differentiation of malignant from benign

lesions. The clinical finding of a hard scrotal mass

in our patient raised concerns of malignancy, and

hence surgical exploration was undertaken. The final

diagnosis still depends on biopsy and pathological

study. In our patient, histology and immunological

studies of the scrotal wall biopsy hinted at the

final diagnosis of occult gastric adenocarcinoma.

Although positron emission tomography–CT may

be useful for seeking an occult primary malignancy,

it is not commonly used as a first-line imaging

modality in patients presenting with a scrotal

wall lesion. However, it could be offered to search

for an underlying primary when histology shows

adenocarcinoma but immunological study results are

pending.

Conclusion

Extra-testicular metastases are rare and

have non-specific

sonographic features, which always pose

difficulties in diagnosis, particularly in patients

without a known primary malignancy. We hereby

report the first case of a gastric adenocarcinoma

presenting as scrotal wall metastasis. This case also

demonstrates the importance of radiological, clinical,

and pathological correlations in making the final

diagnosis.

References

1. Woodward PJ, Schwab CM,

Sesterhenn IA. From the archives of the AFIP: extratesticular

scrotal masses: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics

2003;23:215-40. Crossref

2. Dogra V, Saad W, Rubens DJ.

Sonographic appearance of scrotal wall metastases from lung

adenocarcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2002;179:1647-8. Crossref

3. Dutt N, Bates AW, Baithun SI.

Secondary neoplasms of the male genital tract with different

patterns of involvement in adults and children. Histopathology

2000;37:323-31. Crossref

4. Algaba F, Santaularia JM,

Villavicencio H. Metastatic tumor of the epididymis and spermatic

cord. Eur Urol 1983;9:56-9.

5. Dogra VS, Gottlieb GH, Oka M,

Rubens DJ. Sonography of the scrotum. Radiology 2003;227:18-36. Crossref

6. Aridogan IA, Satar N, Doran E,

Tansug MZ. Scrotal skin metastases of renal cell carcinoma: a case

report. Acta Chir Belg 2004;104:599-600.

7. McWeeney DM, Martin ST, Ryan RS,

Tobbia IN, Donnellan PP, Barry KM. Scrotal metastases from

colorectal carcinoma: a case report. Cases J 2009;2:111. Crossref

8. Wang SQ, Mecca PS, Myskowski PL,

Slovin SF. Scrotal and penile papules and plaques as the initial

manifestation of a cutaneous metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the

prostate: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol

2008;35:681-4. Crossref

9. Hanash KA, Carney JA, Kelalis

PP. Metastatic tumors to the testicles: routes of metastasis. J

Urol 1969;102:465-8.

10. Moghe PK, Brady AP. Ultrasound

of testicular epidermoid cysts. Br J Radiol 1999;72:942-5.

11. Akbar SA, Sayyed TA, Jafri SZ,

Hasteh F, Neill JS. Multimodality imaging of paratesticular

neoplasms and their rare mimics. Radiographics 2003;23:1461-76. Crossref

12. Ferguson MA, White BA, Johnson

DE, Carrington PR, Schaefer RF. Carcinoma en cuirasse of the

scrotum: an unusual presentation of lung carcinoma metastatic to

the scrotum. J Urol 1998;160(6 Pt 1):2154-5.

13. Alleman WG, Gorman B, King BF,

Larson DR, Cheville JC, Nehra A. Benign and malignant epididymal

masses evaluated with scrotal sonography: clinical and pathologic

review of 85 patients. J Ultrasound Med 2008;27:1195-202.

14. Cassidy FH, Ishioka KM,

McMahon CJ, et al. MR imaging of scrotal tumors and pseudotumors.

Radiographics 2010;30:665-83. Crossref

15. Souza FF, Di Salvo D.

Sonographic features of a metastatic extratesticular

gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Ultrasound Med 2008;27:1639-42.