Hong Kong Med J 2017 Jun;23(3):264–71 | Epub 5 May 2017

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj166124

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

How well are we managing fragility hip fractures? A narrative report on the review with the attempt to set up a Fragility Fracture Registry in Hong Kong

KS Leung, MD, FHKCOS1;

WF Yuen, BNurs, MSc1;

WK Ngai, MB, BS, FHKCOS2;

CY Lam, MB, BS, FHKCOS3;

TW Lau, MB, BS, FHKCOS4;

KB Lee, MB, ChB, FHKCOS5;

KM Siu, MB, ChB, FHKCOS6;

N Tang, MB, ChB, FHKCOS7;

SH Wong, MB, BS, FHKCOS8;

WH Cheung, BSc, PhD1

1 Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

2 Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, North District Hospital,

Sheung Shui, Hong Kong

3 Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Tuen Mun Hospital,

Tuen Mun, Hong Kong

4 Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Queen Mary Hospital,

Pokfulam, Hong Kong

5 Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Queen Elizabeth

Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

6 Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Princess Margaret

Hospital, Laichikok, Hong Kong

7 Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Prince of Wales

Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

8 Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Caritas Medical Centre,

Shamshuipo, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KS Leung (ksleung@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: In setting up a disease registry for

fragility fractures in Hong Kong, we conducted a

retrospective systematic study on the management

of fragility hip fractures. Patient outcomes were

compared with the standards from our orthopaedic

working group and those from the British

Orthopaedic Association that runs a mature fracture

registry in the United Kingdom.

Methods: Clinical data on fragility hip fracture

patients admitted to six acute major hospitals in

Hong Kong in 2012 were captured. These included

demographics, pre- and post-operative assessments,

discharge details, complications, and 1-year follow-up

information. Analysis was performed according

to the local standards with reference to those from

the British Orthopaedic Association.

Results: Overall, 91.0% of patients received

orthopaedic care within 4 hours of admission

and 60.5% received surgery within 48 hours.

Preoperative geri-orthopaedic co-management

was received by 3.5% of patients and was one of the

reasons for the delayed surgery in 22% of patients.

Only 22.9% were discharged with medication that

would promote bone health. Institutionalisation on

discharge significantly increased by 16.2% (P<0.001).

Only 35.1% of patients attended out-patient follow-up

1 year following fracture, and mobility had

deteriorated in 69.9% compared with the premorbid

state. Death occurred in 17.3% of patients within a

year of surgery compared with 1.6% mortality rate in

a Hong Kong age-matched population.

Conclusions: The efficiency and quality of acute care

for fragility hip fracture patients was documented.

Regular geri-orthopaedic co-management can

enhance acute care. Much effort is needed to

improve functional recovery, prescription of bone

health medications, attendance for follow-up, and

to decrease institutionalisation. A Fracture Liaison

Service is vital to improve long-term care and

prevent secondary fractures.

New knowledge added by this study

- This was the first study to review the standards and clinical outcomes of 2914 patients from six major hospitals in Hong Kong with fragility hip fracture.

- Strengths and weaknesses of current fragility hip fracture management were identified. Recommendations are made to improve care.

- This study was the first phase in the process of setting up a Fragility Fracture Registry and reveals the usefulness of a disease registry for improving patient care.

Introduction

Fragility hip fracture is one of the most common

fragility fractures and is becoming one of the major

health care burdens on a society with an ageing

population. Statistics of the Hospital Authority (HA)

of Hong Kong (HK) reveal that the incidence of

fragility fractures in 2014 (14 000 cases) was much

higher than that for acute myocardial infarction

(6383 cases) or acute cerebrovascular accident

(11 187 cases). Number of patients admitted for hip

fracture surgery increased from 3678 in 2000 to 4579

in 2011, ie 24.5% in 11 years.1 Although the annual

age-specific risk of hip fracture slightly decreased, it is

estimated that with the projected ageing population,

fragility hip fractures in HK will number more than

6300 cases in 2020 and 14 500 cases in 2040, a 3-fold

increase from 2011.1 Approximately 30% of patients

under the age of 80 years were unable to walk

independently 1 year after hip fracture and became

home-bound; 20% to 40% of patients were admitted

to an elderly care home; and all patients suffered

both physically and psychologically with re-fracture

and fear of falls.2 Hip fracture patients with poor

functional recovery are unable to resume their pre-fracture

function with a consequent deterioration in

quality of life. Mortality at 1 year after hip fracture

was as high as 27% in males and 15% in females.1

To monitor the outcomes of management

and formulate standards of care in HK for fragility

hip fracture, the Coordinating Committee in

Orthopaedics & Traumatology of the HA proposed

a Fragility Fracture Registry (www.ffr.hk) in 2013.

It is hoped that the registry will ultimately help set

the standards of care with respect to local demands,

monitor patient care and implement preventive

measures, thus improving the cost-effectiveness of

fragility fracture care.

In the first phase of setting up the Fragility

Fracture Registry, a retrospective study was

conducted of fragility hip fractures treated at six

acute public hospitals under the management of the

HA. This study aimed to review the current fragility

hip fracture management in HK, and compare the

outcomes with the standards set by our working

group with reference to the six evidence-based

standards set by the British Orthopaedic Association

(BOA) for the care of patients with fragility hip

fracture.3

Methods

All patients with fragility hip fracture and admitted

in the calendar year 2012 to the six hospitals in

HK—Caritas Medical Centre, Prince of Wales

Hospital, Princess Margaret Hospital, Queen

Elizabeth Hospital, Queen Mary Hospital, and

Tuen Mun Hospital—which are located in different

clusters were included. Residents of HK aged 50

years and above with hip fracture sustained by a fall

from a standing height were recruited. The number

of fragility hip fractures from the six hospitals was

approximately 60% of the total fragility hip fractures

treated in Hong Kong during 2012. Those with

atypical or pathological fracture were excluded.

As 98% of patients with fragility hip fracture were

managed in public hospitals, eligible patients were

identified using the HA Clinical Data Analysis and

Reporting System with disease coding of acute hip

fracture (ICD-9-CM 820.X).4 Ethical approvals were obtained from all the six hospitals and the study was done in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

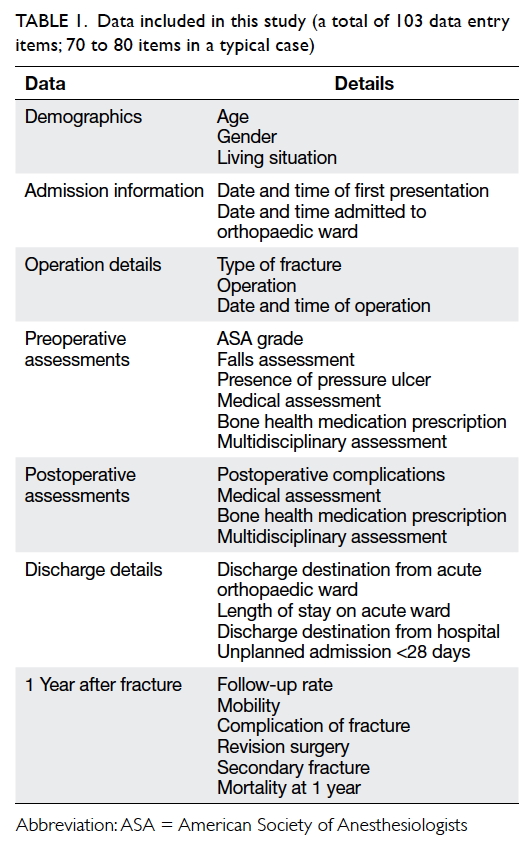

With reference to the National Hip Fracture

Database of the United Kingdom (UK NHFD)

and Scottish Hip Fracture Audit, the dataset was

designed according to the acute, rehabilitation, and

post-discharge practices in HK. Information was

derived from the HA Clinical Management System

and hospital records for the following: demographics,

preoperative and postoperative assessments,

surgical and discharge details, rehabilitation

details, out-patient follow-up consultations and

complications up to 1 year after fracture (Table 1).

All data were input and managed using the Research

Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tool hosted at

the Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology,

Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong

Kong.5

Table 1. Data included in this study (a total of 103 data entry items; 70 to 80 items in a typical case)

Data were input by research assistants who

understood medical terms and abbreviations. Data

were validated for one in five cases selected randomly

by six liaison teams located in the participating

hospitals and composed of orthopaedic surgeons

and nurses. Each liaison member was trained by the

central research team in data validation and REDCap

manipulation.

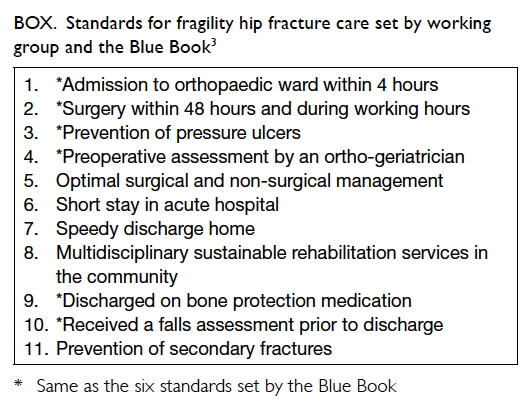

The data were analysed and compared with the

standards set by our working group with reference

to the six standards set by the BOA: Care of Patients

with Fragility Fractures (known as the Blue Book;

Box).3

Descriptive statistics were used to describe

the current hip fracture conditions in HK and

outcomes compared with standards of care from

HK orthopaedic working group with reference to

BOA. The percentage was calculated based on the

number of follow-up patients available at different

time-points. Chi squared test was used to compare

categorical data. The Statistical Package for the

Social Sciences (Windows version 20.0;

IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], US) was used to perform

statistical analysis. Significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Demographics

A total of 2914 fragility hip fractures were captured

in the calendar year 2012 and the mean (± standard

deviation) patient age was 82.1 ± 8.6 years (range,

50-104 years). Of the patients, 1979 (67.9%) were

female; 2017 (73.7%) came from home and 719

(26.3%) from an elderly care home; 1119 (40.9%),

1541 (56.3%), and 20 (0.7%) patients had an American

Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score of grade 2,

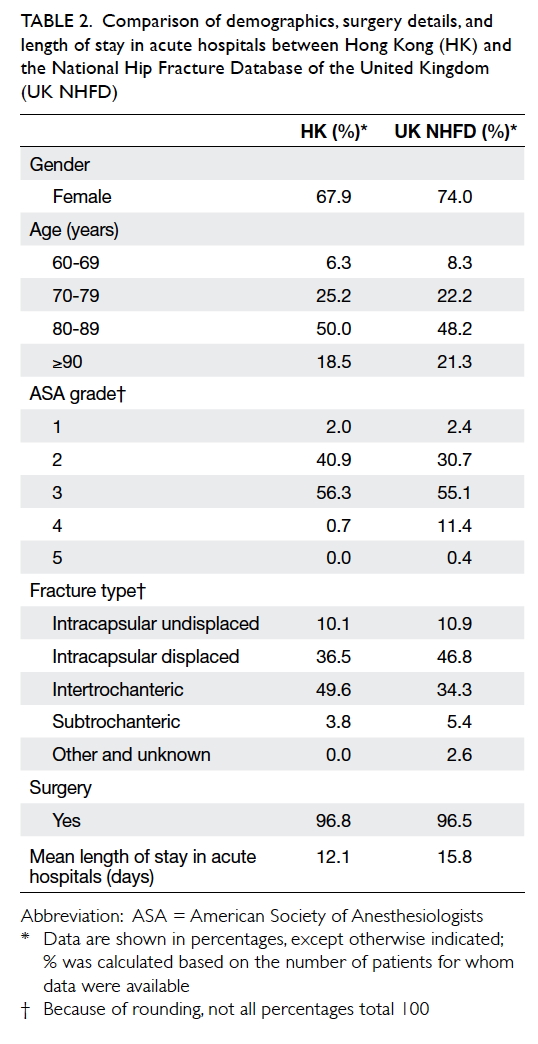

3, and 4, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of demographics, surgery details, and length of stay in acute hospitals between Hong Kong (HK) and the National Hip Fracture Database of the United Kingdom (UK NHFD)

Acute management

The mean time from presentation to the accident

and emergency department to orthopaedic care

was 2.3 hours (median time, 1.7 hours) with 91.0%

patients receiving orthopaedic care within 4 hours.

Geriatric or internal medicine review was performed

in 764 (27.8%) patients although only 95 (3.5%) were

routinely managed by a geriatrician preoperatively.

Surgery was performed in 2774 (96.8%)

patients. The mean time to surgery was 62.7 hours

(median time, 42.1 hours) with 1678 (60.5%)

undergoing surgery in exactly 48 hours and 2172

(78.3%) within 2 calendar working days.

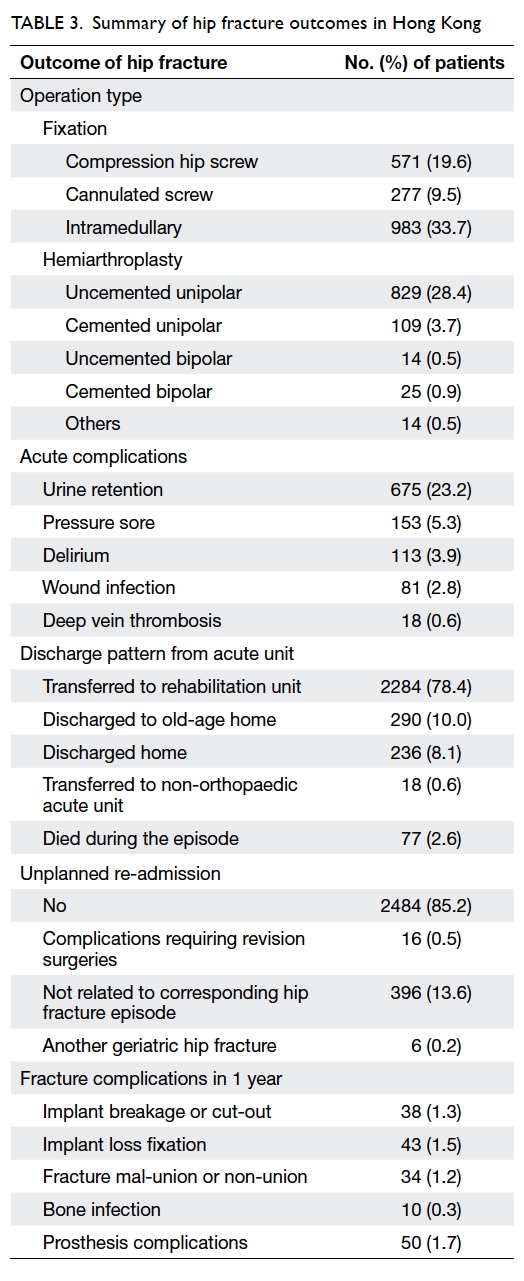

Intracapsular fracture occurred in 1358 (46.6%)

patients of whom 277 (9.5%) underwent cannulated

screw fixation, 829 (28.4%) uncemented unipolar

hemiarthroplasty, and 109 (3.7%) cemented unipolar

hemiarthroplasty. Intertrochanteric fracture

occurred in 1446 (49.6%) patients of whom 571

(19.6%) underwent compression hip screw fixation

and 983 (33.7%) intramedullary fixation (Tables 2 and 3).

During stay in acute hospitals, some of the

patients developed acute complications, with nearly

one fourth experienced urine retention. A small

number of patients developed other complications

like pressure sore, delirium, wound infection, and

deep vein thrombosis (Table 3).

The mean length of stay in acute hospitals was

12.1 days. With regard to the discharge destination

from the acute unit, a majority of patients (2284,

78.4%) were transferred to a rehabilitation unit,

290 (10.0%) to an old-age home, 236 (8.1%) to their

previous home, and 77 (2.6%) died during the acute

admission (Table 3).

Rehabilitation phase

Allied health professionals provided preoperative

multidisciplinary care to 1759 (64.0%) patients and

postoperative care to 2886 (99.4%). Bone health

medication was prescribed to 424 (15.3%) patients

preoperatively and 666 (22.9%) postoperatively.

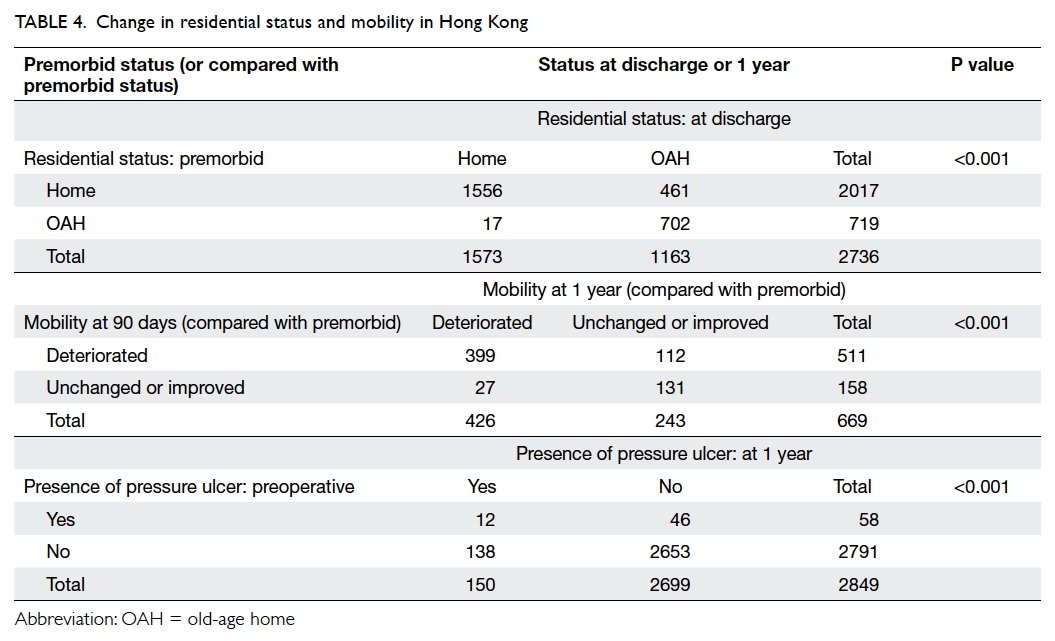

Just over half of all patients (n=1573, 57.5%) were

discharged to their home and 1163 (42.5%) to an

old-age home. Old-age home admission at discharge

significantly increased (P<0.001) [Table 4].

Post-discharge management

There was a declining trend over time for attendance

at follow-up; 2179 (74.8%) attended follow-up at 90

days after fracture, 2508 (86.1%) at 180 days, and

only 1023 (35.1%) at 1 year. Postoperative mobility

compared with premorbid had deteriorated at

90-day, 180-day, and 1-year follow-up in 1689

(77.5%), 2062 (82.2%), and 715 (69.9%) patients,

respectively. With those 669 patients available for

assessments at both 90-day and 1-year time-points,

511 patients had deterioration at 90 days and 426

patients deteriorated at 1 year. The deterioration was

significant at 1-year follow-up (P<0.001) [Table 4].

Pressure sores were evident or developed in 58 (2.0%)

patients preoperatively and 150 (5.3%) at 1 year.

Presence of pressure sore significantly increased at 1

year (P<0.001) [Table 4].

Fracture complications occurred in 175 (6.0%)

patients within a year (Table 3) with 90 (3.1%)

requiring revision surgery. A secondary fracture

occurred in 117 (4.0%) patients and 505 (17.3%)

patients died in 1 year compared with the 1.6%

mortality rate for a HK age-matched population.6 7

Discussion

This report reviewed the management of fragility

hip fractures in HK based on the standards of care

by our orthopaedic community and compared the

outcomes with the standards set by our working

group and by BOA in the UK.

The demographics were comparable to

previous studies in HK. The mean age of patients

with fragility hip fracture in our 2012 data was 82.1

years, unchanged compared with local data from

2000 to 2011.1 The female-to-male ratio was around

2:1 indicating an increase in male fragility hip

fractures compared with 2.5:1 from 2001 to 2010.4 8 This may be due to increasing life expectancy of

the HK male population9 and bone mineral density

(BMD) at the hip in men that decreases with age.10

There were 1257 (46.6%) femoral neck fractures,

1445 (49.6%) intertrochanteric fractures, and 110

(3.8%) subtrochanteric fractures, comparable with

a previous local study of 1342 hip fracture patients

from 2007 to 2010.8 The majority of patients had an

ASA score of 2 and 3, comprising 40.9% and 56.3%,

respectively and in line with Lau et al’s study.8 There

was a marked increase in hemiarthroplasties and

intramedullary fixations with 977 (33.5%) and 983

(3.7%) cases respectively in our study, compared

with Lau et al’s study that reported 362 (27%)

hemiarthroplasties and 218 (16%) cephalomedullary

nail fixations.8 This reflects a change in the surgical

treatment, possibly due to a lower re-operation

rate,11 better functional outcomes,12 and higher cost-effectiveness13 in patients treated with

hemiarthroplasty; and minimal rate of fixation

failure, less blood loss, and shorter length of hospital

stay in patients treated with intramedullary fixation.14

A low complication rate (6.0%) and revision

rate (3.1%) are testimony to the improved standard of

routine acute care, which includes early orthopaedic

care and early surgeries.

Consequences of fragility hip fracture

Poor functional recovery was evident in the large

proportion of patients (77.5%) with deteriorated

mobility at 90-day out-patient clinic follow-up, not

improved 1 year after fracture (69.9%). This compares

with less than half of treated patients who regained

their pre-fracture mobility in another study.15

According to an internal survey conducted at Prince

of Wales Hospital, only 22% of patients received

out-patient physiotherapy; the major reason (71%)

was “not referred”. Inadequate rehabilitation after

discharge may explain poor functional recovery after

hip fracture. On discharge, HK patients discharged to

an old-age home significantly increased from 26.3%

to 42.5%, ie a 16.2% increase in institutionalisation

compared with only 10.5% in a Spanish study.16

Poor functional recovery after hip fracture may

contribute to this high institutionalisation rate, as

fractures are significantly associated with mild-to-severe functional limitations.17 Lack of support

in the community may mean a lack of sustained

rehabilitation after discharge. Family support may

also be suboptimal as many elderly are alone at home

during the day.

Low follow-up attendance and high mortality

The attendance rate for out-patient clinic follow-up

was only 35.1% at 1 year. A high proportion of

elderly living alone (12.7% in 2011)18 and a high

institutionalisation rate (5.7% in 2014)19 may explain

the low follow-up rate due to lack of support.

The mortality at 1 year after fracture was 17.3%,

comparable with other local studies: 18.6% from

2000 to 20061 and 18.0% from 2001 to 2009,4 which are much higher than that for an age-matched

population (1.6%).6 7

Comparison with standards in the United Kingdom

Data from this review were also compared with those

of the UK NHFD 201220 collected from 180 hospitals

across the UK with patients managed according to

the UK Blue Book standards.3

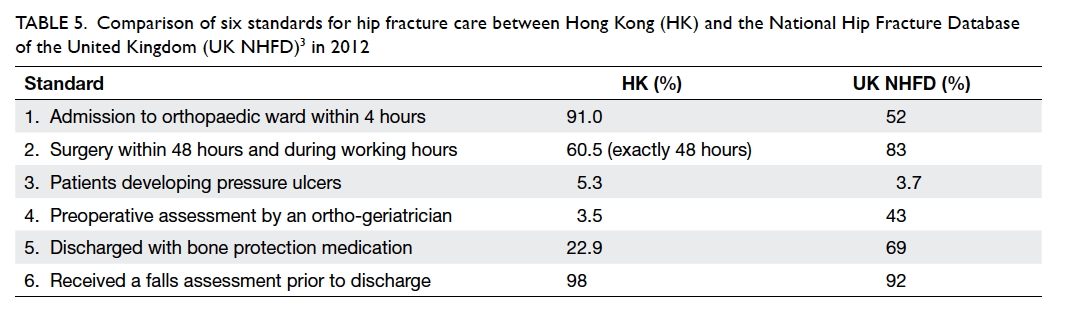

Tables 2 and 5 summarise the demographics,

surgery details, length of stay in acute hospitals, and

comparison of six standards for hip fracture care

between HK and UK NHFD, respectively. Major

differences in hip fracture management between HK

and UK NHFD are identified.

Table 5. Comparison of six standards for hip fracture care between Hong Kong (HK) and the National Hip Fracture Database of the United Kingdom (UK NHFD)3 in 2012

When comparing the demographics, our

review showed a larger male hip fracture population

(32%) than the UK (26%) while age and ASA grade

distribution were similar. Patients treated surgically

were similar in both databases; more HK patients

had intertrochanteric fracture (49.6% vs 34.3%)

and more UK patients had displaced intracapsular

fracture (46.8% vs 36.5%). The length of stay in acute

hospitals in HK was shorter than in UK (12.1 days vs

15.8 days). The mean length of post-acute stay in the

UK was only 4.4 days, however, which is shorter than

that in HK (around 3-4 weeks). This may be due to the

differences in acute and post-discharge care between

HK and the UK. Care by a general practitioner after

being discharged from hospital is the usual practice

in the UK; in HK, most patients will be cared for by

an orthopaedic team in post-acute rehabilitation

with follow-up in orthopaedic specialist clinics until

discharge.

In HK, 98% of patients underwent a falls

assessment on admission, similar to the UK (92%).

In HK, a Morse Fall Scale27 will be calculated by

orthopaedic nurses on admission; in the UK, a

systematic assessment is performed by a geriatrician

or a specialist nurse to prevent further falls.8

Quick surgery under Key Performance Indicator

With regard to the six standards for hip fracture care

set by the BOA Blue Book (Box and Table 5), 61%

of HK patients had surgery within exactly 48 hours,

compared with 35% in Spain21 and less than 10% in

China22; in the UK, 83% of patients received surgery

within 48 hours and during working hours. The

percentage of HK patients who underwent surgery

within 2 calendar working days was 30% before 2007 and

improved to 62% in 2008 after the establishment

of Key Performance Indicator (KPI) by the HA and

78.3% in 2012.23 The aim of KPI is to ensure 70% of hip

fracture patients receive surgery within 2 calendar working

days.24 25 This may explain why a large proportion of patients had quick hip fracture surgery in HK. The

delay in surgery for 22% of patients may have been

due to time spent awaiting medical optimisation by

physicians or geriatricians.

Importance of geri-orthopaedic co-management

Very few patients in HK (3.5%) received preoperative

assessment by geriatricians in contrast to 43% of

patients in the UK. In this review, only one of the

six studied hospitals had a geriatrician who routinely

assessed hip fracture patients pre- and post-operatively,

indicating a lack of geri-orthopaedic

co-management in HK. Studies have shown better

outcomes after hip fracture when patients receive

geri-orthopaedic treatment, with a lower 1-year

mortality rate,26 27 reduced acute hospital stay, and less need for further rehabilitation.27 A local study

reviewed the effectiveness of geri-orthopaedic co-management

and found that in the geri-orthopaedic

group, time to surgery was shorter, 1-year mortality

rate was lower, and more remained independent in

daily living activities.28 Therefore, geri-orthopaedic

care should be implemented in all hospitals in HK to

achieve better patient care. This will further improve

the KPI for fragility hip fractures in all hospitals in

HK.

Low prescription rate of bone protection medication

Only 23% of HK patients were discharged with

bone protection medication compared with almost

70% in the UK (Table 5) and nearly 40% in Korea

(excluding calcium and vitamin D).29 A local study

showed that 33% were prescribed medications for

osteoporosis in the 6 months after discharge.30

Osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment were driven

by BMD measurement, not fracture history.30

This may explain the low prescription rate of bone

protection medication when the fracture patient

did not undergo BMD measurement for a variety of

reasons such as unavailability of dual-energy X-ray

absorptiometry (DXA), long queuing time, or lack

of referral from orthopaedic doctors. Although the

need for DXA measurement prior to prescription

of bone health medication to patients with fragility

fracture remains controversial, it is clear that DXA

measurement is not the only single indication for

such medication.31

Importance of Fracture Liaison Services

In view of the low follow-up rate, poor functional

recovery, increased institutionalisation, and high

mortality after fragility hip fracture, better post-discharge

rehabilitation and secondary fracture

prevention should be implemented to restore

patients’ physical and psychological status.

Fracture Liaison Services (FLS) is a coordinator-based

service for sustained rehabilitation in the

community and secondary fracture prevention

in patients with fragility fractures. It has been

implemented in many countries—eg the UK,32

Australia,33 Canada34—and studies reveal that

FLS is cost-effective. Implementation of FLS in

HK may improve current post-discharge care.

Such services include osteoporosis identification

and treatment (eg DXA scan and prescription of

bone protection medication), education about

secondary fracture prevention (exercise, dietary

guidelines, and an education programme), and

sustainable multidisciplinary services (follow-up by

FLS coordinator regularly). With FLS, fragility hip

fracture patients with osteoporosis can be identified

and treated promptly with good compliance with

medications. Patients will be instructed to exercise

to improve functional status with a potential

consequent decrease in old-age home admission.

They will also be taught about falls prevention and

sustained rehabilitation, and hence lower the chance

of secondary fracture.

Limitations of this study

This study included approximately 60% of all

HK fragility hip fractures. It would be better to

include all HK hospitals in future studies to reflect

the full situation across the territory. This study

retrospectively reviewed medical records from 2012

with data retrieved from electronic and handwritten

records so a small percentage of data may have been

missing due to illegible records. A standardised

electronic format from the Clinical Management

System will improve data capture and analysis.

A disease registry is important to enable better

documentation.

Conclusions

This study reviewed the current fragility hip fracture

care in HK. Although acute surgical treatment

complies with international standards, standardised

geri-orthopaedic co-management will further

improve the acute care. Recognising fragility hip

fracture as a chronic disease model, the increased

rate in old-age home admission, poor functional

recovery, low prescription rate of bone health

medications, and low attendance rate for follow-up

were identified as problems in subsequent

management. These may explain the higher 1-year

mortality rate, high secondary fracture rate, and

deterioration in the quality of life after fracture

among these elderly. With an ageing population

and increasing longevity, the hip fracture rate is

expected to increase continuously. A comprehensive

multidisciplinary chronic disease management model

that includes geri-orthopaedic co-management and

FLS programmes should be implemented to improve

patient outcomes, prevent secondary fractures, and

reduce the economic burden on HK. The setting up

and maintenance of a registry of all fragility fractures

is imminent and will help health care professionals

monitor and continuously improve the standards of

patient care as well as prevent fractures.

Acknowledgements

This study was partially supported by grant support

of Asian Association for Dynamic Osteosynthesis

(Ref: AADO-RF2012-001-2Y) and Professional

Services Development Assistance Scheme,

Commerce and Economic Development Bureau,

Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. The authors would like to thank the liaison

teams that comprised doctors and nurses of the

Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology

from the six participating hospitals for their help in

data validation.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Man LP, Ho AW, Wong SH. Excess mortality for operated

geriatric hip fracture in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J

2016;22:6-10. Crossref

2. Fierens J, Broos PL. Quality of life after hip fracture surgery

in the elderly. Acta Chir Belg 2006;106:393-6. Crossref

3. The care of patients with fragility fracture. British

Orthopaedic Association; 2007.

4. Chau PH, Wong M, Lee A, Ling M, Woo J. Trends in hip

fracture incidence and mortality in Chinese population

from Hong Kong 2001-09. Age Ageing 2013;42:229-33. Crossref

5. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N,

Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a

metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for

providing translational research informatics support. J

Biomed Inform 2009;42:377-81. Crossref

6. Population estimates. Census and Statistics Department,

Hong Kong SAR Government; 2016.

7. Tables on health status and health services 2012.

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government;

2013.

8. Lau TW, Fang C, Leung F. The effectiveness of a geriatric

hip fracture clinical pathway in reducing hospital and

rehabilitation length of stay and improving short-term

mortality rates. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2013;4:3-9. Crossref

9. Women and men in Hong Kong key statistics. Census and

Statistics Department, Hong Kong SAR Government; 2016.

10. Lau EM, Leung PC, Kwok T, et al. The determinants of

bone mineral density in Chinese men—results from Mr.

Os (Hong Kong), the first cohort study on osteoporosis in

Asian men. Osteoporos Int 2006;17:297-303. Crossref

11. Shields E, Kates SL. Revision rates and cumulative financial

burden in patients treated with hemiarthroplasty compared

to cannulated screws after femoral neck fractures. Arch

Orthop Trauma Surg 2014;134:1667-71. Crossref

12. Gjertsen JE, Vinje T, Engesaeter LB, et al. Internal screw

fixation compared with bipolar hemiarthroplasty for

treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures in elderly

patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010;92:619-28. Crossref

13. Waaler Bjornelv GM, Frihagen F, Madsen JE, Nordsletten

L, Aas E. Hemiarthroplasty compared to internal fixation

with percutaneous cannulated screws as treatment of

displaced femoral neck fractures in the elderly: cost-utility

analysis performed alongside a randomized, controlled

trial. Osteoporos Int 2012;23:1711-9. Crossref

14. Ma KL, Wang X, Luan FJ, et al. Proximal femoral nails

antirotation, Gamma nails, and dynamic hip screws for

fixation of intertrochanteric fractures of femur: a meta-analysis.

Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2014;100:859-66. Crossref

15. Vochteloo AJ, Moerman S, Tuinebreijer WE, et al. More

than half of hip fracture patients do not regain mobility

in the first postoperative year. Geriatr Gerontol Int

2013;13:334-41. Crossref

16. Uriz-Otano F, Pla-Vidal J, Tiberio-López G, Malafarina

V. Factors associated to institutionalization and mortality

over three years, in elderly people with a hip fracture—An

observational study. Maturitas 2016;89:9-15. Crossref

17. Woo J, Ho SC, Yu LM, Lau J, Yuen YK. Impact of chronic

diseases on functional limitations in elderly Chinese aged

70 years and over: a cross-sectional and longitudinal

survey. J Gerontol A Bio Sci Med Sci 1998;53:M102-6. Crossref

18. Thematic report: older persons. Census and Statistics

Department, Hong Kong SAR Government; 2011.

19. Challenges of population ageing. Research Brief, Issue

1, 2015-2016. Hong Kong: Research Office, Legislative

Council Secretariat; 2015.

20. National report 2012. The UK National Hip Fracture

Database; 2012.

21. Vidán MT, Sánchez E, Gracia Y, Marañón E, Vaquero J, Serra JA. Causes and effects of surgical delay in patients

with hip fracture: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:226-33. Crossref

22. Tian M, Gong X, Rath S, et al. Management of hip fractures

in older people in Beijing: a retrospective audit and

comparison with evidence-based guidelines and practice

in the UK. Osteoporos Int 2016;27:677-81. Crossref

23. Lau PY. To improve the quality of life in elderly people.

Hong Kong Med J 2016;22:4-5.

24. New framework for key performance indicators (AOM-P530).

Hong Kong: Hospital Authority; 2008.

25. Guidebook on key performance indicators. 2nd ed. Hong

Kong: Hospital Authority; 2015.

26. Folbert EC, Hegeman JH, Vermeer M, et al. Improved

1-year mortality in elderly patients with a hip fracture

following integrated orthogeriatric treatment. Osteoporos

Int 2017;28:269-77. Crossref

27. Henderson CY, Shanahan E, Butler A, et al. Dedicated

orthogeriatric service reduces hip fracture mortality. Ir J

Med Sci 2017;186:179-84. Crossref

28. Leung AH, Lam TP, Cheung WH, et al. An orthogeriatric

collaborative intervention program for fragility fractures: a

retrospective cohort study. J Trauma 2011;71:1390-4. Crossref

29. Kim SC, Kim MS, Sanfélix-Gimeno G, et al. Use of

osteoporosis medications after hospitalization for hip

fracture: a cross-national study. Am J Med 2015;128:519-26.e1. Crossref

30. Kung AW, Fan T, Xu L, et al. Factors influencing diagnosis

and treatment of osteoporosis after a fragility fracture

among postmenopausal women in Asian countries: a

retrospective study. BMC Womens Health 2013;13:7. Crossref

31. Ito K, Leslie WD. Cost-effectiveness of fracture prevention

in rural women with limited access to dual-energy X-ray

absorptiometry. Osteoporos Int 2015;26:2111-9. Crossref

32. McLellan AR, Gallacher SJ, Fraser M, McQuillian C.

The fracture liaison service: success of a program for the

evaluation and management of patients with osteoporotic

fracture. Osteoporos Int 2003;14:1028-34. Crossref

33. Cooper MS, Palmer AJ, Seibel MJ. Cost-effectiveness of

the Concord Minimal Trauma Fracture Liaison service,

a prospective, controlled fracture prevention study.

Osteoporos Int 2012;23:97-107. Crossref

34. Bogoch ER, Elliot-Gibson V, Beaton DE, Jamal SA, Josse

RG, Murray TM. Effective initiation of osteoporosis

diagnosis and treatment for patients with a fragility

fracture in an orthopaedic environment. J Bone Joint Surg

Am 2006;88:25-34. Crossref