Hong Kong Med J 2017 Jun;23(3):246–50 | Epub 27 Jan 2017

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj164880

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Comparison of a commercial interferon-gamma

release assay and tuberculin skin test for the

detection of latent tuberculosis infection in Hong

Kong arthritis patients who are candidates for

biologic agents

H So, MSc, FHKAM (Medicine);

Carol SW Yuen, BNurs, MSc;

Ronald ML Yip, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)

Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Kwong Wah Hospital, Yaumatei,

Hong Kong

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the ASM of the Hong

Kong Society of Rheumatology held in Hong Kong on 22 November 2015.

Corresponding author: Dr H So (h99097668@hotmail.com)

Abstract

Introduction: It is universally agreed that screening

for latent tuberculosis infection prior to biologic

therapy is necessary, especially in endemic areas

such as Hong Kong. There are still, however,

controversies regarding how best to accomplish this

task. The tuberculin skin test has been the routine

screening tool for latent tuberculosis infection in

Hong Kong for the past decade although accuracy

is far from perfect, especially in patients who have

been vaccinated with Bacillus Calmette–Guérin,

who are immunocompromised, or who have atypical

mycobacterium infection. The new interferon-gamma

release assays have been shown to improve specificity

and probably sensitivity. This study aimed to

evaluate agreement between the interferon-gamma

release assay and the tuberculin skin test in the

diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection in patients

with arthritic diseases scheduled to receive biologic

agents.

Methods: We reviewed 38 patients with rheumatoid

arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, or spondyloarthritis at a

local hospital in Hong Kong from August 2013 to April

2014. They were all considered candidates for biologic

agents. The patients underwent both the interferon-gamma

release assay (ASACIR.TB; A.TB) and the

tuberculin skin test simultaneously. Concurrent

medications were documented. Patients who tested

positive for either test (ie A.TB+ or TST+) were

prescribed treatment for latent tuberculosis if they

were to be given biologic agents. All patients were

followed up regularly for 1 year and the development

of active tuberculosis infection was evaluated.

Results: Based on an induration of 10 mm in diameter

as the cut-off value, 13 (34.2%) of 38 patients had a

positive tuberculin skin test. Of the 38 patients, 11

(28.9%) also had a positive interferon-gamma release

assay. The agreement between interferon-gamma

release assay and tuberculin skin test was 73.7%

(kappa=0.39). Six patients were TST+/A.TB– and four

were TST–/A.TB+. When positive tuberculin skin

test was defined as an induration of 5-mm diameter,

the agreement between the two tests improved with

a kappa value of 0.47. In that case, half of the patients

had a positive tuberculin skin test; among them,

nine were TST+/A.TB–. Only one was TST–/A.TB+. Subgroup analysis showed that the agreement

between both tests improved further (kappa=0.69) in

patients not taking a concurrent systemic steroid. For

patients prescribed systemic steroid, the agreement

was only slight with a kappa value of 0.066. Finally,

none of the 38 patients, of whom 32 had an exposure

to biologic agents, developed active tuberculosis

during the 1-year follow-up period.

Conclusion: In a tuberculosis-endemic population,

although 10-mm diameter induration is the usual

cut-off for a positive tuberculin skin test, the level

of agreement between the interferon-gamma release

assay and tuberculin skin test improved from fair to

moderate when the cut-off was lowered to 5 mm.

A dual testing strategy of tuberculin skin test and

interferon-gamma release assays appeared to be

effective and should be pursued especially in patients

who are on systemic steroid therapy. Nonetheless, the

issue of potential overtreatment is yet to be evaluated.

New knowledge added by this study

- In Hong Kong, a tuberculosis-endemic area, the level of agreement between tuberculin skin test (TST) and interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) for detecting latent tuberculosis infection was only fair in arthritis patients scheduled to receive biologic therapy.

- Although 10 mm is the cut-off for positive TST according to the local guideline, the level of agreement between the two tests improved when a 5-mm cut-off was used.

- Dual testing strategy with TST and IGRA appeared to be effective and should be employed, especially in patients who are prescribed systemic steroid therapy.

Introduction

The advent of biologic agents has revolutionised

the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis

(RA), psoriatic arthritis (PSA), and spondyloarthritis

(SPA). The outcome is now greatly improved. This,

however, comes at the price of a clear heightened risk

of active tuberculosis (TB) as a progression of latent

TB infection (LTBI).1 Therefore, it is universally

agreed that screening for LTBI prior to biologic

therapy is necessary, especially in endemic areas

such as Hong Kong.2 Unfortunately, there remains

controversy regarding how best to accomplish this

task.

The tuberculin skin test (TST) has been

the routine screening tool in Hong Kong for

the past decade.3 Its accuracy, however, is far

from perfect, especially in patients who have

been vaccinated with Bacillus Calmette–Guérin

(BCG), are immunocompromised, or have been

infected with atypical mycobacterium.4 Recently,

interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs) that

measure interferon-gamma secretion in response to

Mycobacterium tuberculosis–specific antigens have

become available to detect LTBI. They have been

shown to offer improved specificity and probably

sensitivity.5 6 Other shortcomings of the TST, such as the need for return visits and reader variability, are

also overcome. One of the IGRAs, the ASACIR.TB

(A.TB; Haikou VTI Biological Institute, Hainan,

China), has shown encouraging results in a large-scale

clinical trial conducted in China and might be

more appropriate in Chinese populations.7

On the other hand, IGRAs are not flawless.

The rate of indeterminate results has been reported

to be as high as 40%.8 The immunocompromised

state of arthritic patients will also induce a depressed

response to a T-cell reaction leading to an inaccurate

IGRA result. There are recent data to argue that an

IGRA alone is insufficient to identify all patients at

risk.9 10 Furthermore, various studies have suggested very different concordance figures between the

IGRA and the TST, likely as a result of heterogeneity

(eg differing background TB prevalence, variable

immunosuppressive therapies, or underlying BCG

status).11

This study aimed to evaluate the

agreement between the IGRA and the TST in the

diagnosis of LTBI in patients with arthritic diseases

scheduled to receive biologic agents in Hong Kong.

Methods

Patients

We reviewed 38 patients with RA, PSA, or SPA at

a local hospital in Hong Kong from August 2013 to

April 2014. They were diagnosed according to the

2010 classification criteria for RA of the American

College of Rheumatology/European League Against

Rheumatism, the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic

Arthritis, and the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis

international Society classification criteria,

respectively. Patients were included if they

were considered candidates for biologic agents.

Concurrent medications were documented.

Candidates were excluded if they had active TB

infection, a history of incomplete TB treatment, or

no measured induration. Patients underwent both

the IGRA and the TST simultaneously. Those who

tested positive for either test and who were due to

be prescribed biologic agents were given latent TB

treatment with isoniazid or rifampicin for 9 months.

All patients were followed up regularly for 1 year

and the development of active TB infection was

evaluated. This study conforms to the provisions

of the Declaration of Helsinki and the guidelines of

the local ethical committee. Informed consent was

considered not necessary due to the retrospective

nature of the study.

Tuberculin skin test

The TST was performed by rheumatologists. A

0.1 mL of 2-TU PPD (tuberculin units of purified

protein derivative) was injected intradermally into

the volar aspect of the forearm. The indurations were

measured in millimetres after 48 hours of inoculation

by rheumatologists who were blinded to the IGRA

results. According to the local guideline, induration

of ≥10 mm was considered a positive result of LTBI.3

Interferon-gamma release assay

We performed the A.TB IGRA test (Haikou VTI

Biological Institute) in all study patients. This assay

employs Haikou VTI’s patented technology (US

patent number 7754219) that enables intracellular

delivery of the full-length protein CFP-10 and the

antigen ESAT-6 to stimulate antigen-specific T-cells

through the major histocompatibility complex class

1 pathway.12 13 The assay was performed according to the user manual. In brief, negative control phosphate

buffered saline (N), positive control concanavalin A (P), and

the TB stimulators CFP-10 and ESAT-6 (T) were

mixed with fresh heparinised whole blood and

incubated for approximately 24 hours at 37.8°C. The

plasma was collected and stored at 48°C for up to 2

weeks. The interferon-gamma level in the plasma was

then determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent

assay. If N was <0.5 IU/mL and (T-N)/(P-N) ≥0.6, or

if N was ≥0.5 IU/mL and (T-N)/(P-N) ≥0.85, the test

was considered to be positive (A.TB+), otherwise the

result was negative (A.TB–).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented as frequencies

and means ± standard deviations as appropriate. The

concordance between TST and IGRA was evaluated

by the Cohen’s weighted k statistic. A kappa value of

>0.6 represents substantial agreement, 0.41 to 0.60

moderate agreement, 0.21 to 0.40 fair agreement, and

<0.21 slight agreement. The concordance was subanalysed

in patients with and without prednisolone.

Results

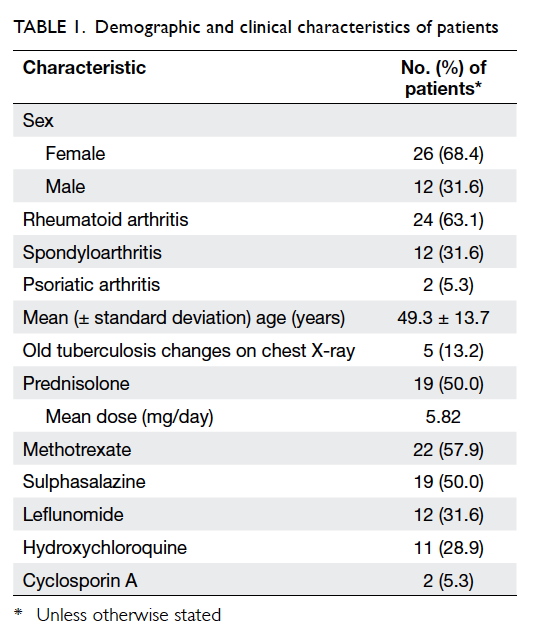

The demographic and clinical characteristics of 38

patients are summarised in Table 1. All patients were

residents of Hong Kong. Half of the patients were

prescribed systemic steroid therapy that comprised

prednisolone at a dose of 2.5 mg daily to 15 mg daily.

All except three patients with SPA were on various

conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic

drugs.

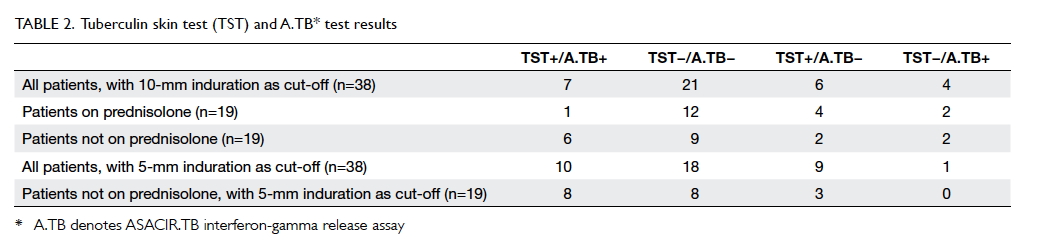

The results of the concomitant TST and IGRA

are shown in Table 2. Of the 38 patients, based on an

induration of 10-mm diameter as the cut-off value,

13 (34.2%) had a positive TST, 11 (28.9%) had a

positive IGRA. The agreement between A.TB IGRA

test and TST was 73.7%. Six patients were TST+/A.TB–

and four were TST–/A.TB+. Subgroup analysis

showed that four of the six divergent TST+/A.TB–

results were in patients on systemic steroid, and only

three patients with systemic steroid were A.TB+

versus eight patients without. When positive TST

was defined as an induration of 5-mm diameter, half

of the patients had a positive TST, among them nine

were TST+/A.TB–. Only one was TST–/A.TB+. In

patients prescribed a systemic steroid, with 5-mm

induration as positivity, TST missed no patients who

had positive IGRAs.

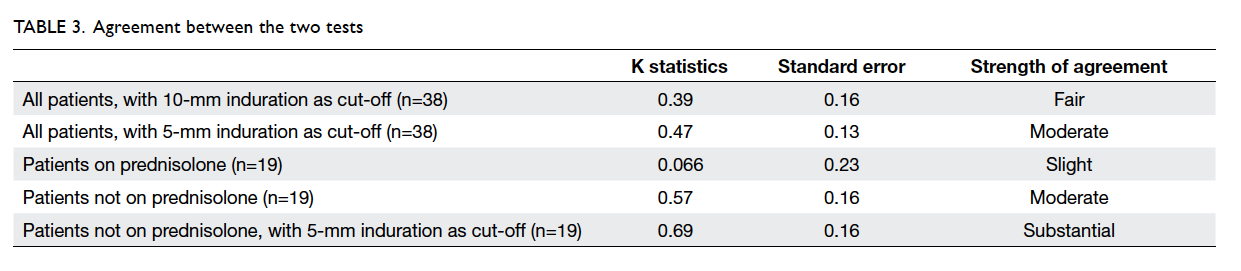

Analysis of the agreement between the two

tests, assessed by kappa statistic, showed only fair

strength in our study, with a kappa value of 0.39

(Table 3). When a 5-mm induration was taken as a

positive TST, however, the agreement between the

two tests improved to moderate with a kappa value of

0.47. Subgroup analysis revealed that the agreement

between both tests improved further (kappa=0.57)

in patients not taking a concurrent systemic steroid.

For patients taking a systemic steroid, the agreement

was only slight (kappa=0.066). Again, the agreement

of the TST and IGRA was substantial (kappa=0.69)

in patients not on systemic steroid therapy when a

5-mm induration was regarded as positive.

At the end of the study, 32 of the initial 38

patients had received biologic agents. None of them

developed active TB during the 1-year follow-up

period.

Discussion

In clinical practice there is no gold standard test for

diagnosing LTBI. Both IGRA and TST have strengths

and weaknesses. In a meta-analysis performed on an

unselected population, the specificity of IGRA was

99% in a non-BCG–vaccinated population and 96%

in a BCG-vaccinated population.14 The specificity

of the TST was 97% in a non-BCG–vaccinated

population but dropped to 59% in a BCG-vaccinated

population.14 In addition to BCG history, comparison

between the two tests must take into account the

underlying disease, the immunosuppression status,

and the background TB burden of the population

being screened.

In this study, we found only a fair agreement

(kappa=0.39) between the results of TST and A.TB IGRA in arthritis patients from a TB-endemic

area. Some studies have also reported a discrepancy

between the two tests in countries with intermediate

TB burden.15 16 Nonetheless, the reported agreement between TST and the IGRA was good (kappa of 0.72 in United Kingdom17 and 0.87 in Denmark18). Consequently, the incidence of TB is a crucial determinant of

agreement between the two tests.

In this study the concordance between the

TST and the IGRA was also affected by immune

status. There was only slight agreement in patients

taking concurrent prednisolone, but the agreement

improved when these patients were excluded

from the analysis. Some previous studies of

immunosuppressed RA patients have shown similarly

poor concordance between the two tests regardless of

TB burden.19 20 There was also discordance between the two tests in LTBI diagnosis among individuals

infected with the human immunodeficiency virus.21

The patients on prednisolone in our study had

a lower rate of positivity for both tests. It seems

intuitive to assume that an immunosuppressed state

will induce a depressed response to a T-cell reaction.

In the literature, a systematic review showed that

both positive IGRA and positive TST results were

significantly influenced by immunosuppressive

therapy.22

The Hong Kong guideline for the TST cut-off

value for LTBI diagnosis before anti-tumour necrosis

factor treatment is an induration of >10 mm.3 In the

current study, we showed that the TST cut-off value

that achieved better agreement between IGRA and

TST results was 5 mm. If we cannot rely on IGRA to

diagnose LTBI, it may be more appropriate to lower

that TST cut-off to 5 mm. We also showed that our

approach to LTBI screening with both TST and

IGRA was successful in preventing the development

of active TB in patients who would receive biologic

therapy. This dual testing strategy might be especially

applicable to patients on systemic steroid, as they are

at higher risk of developing active TB and the two

test results are more discordant. The consequent

improved sensitivity will invariably lower the

specificity and cause a potential overtreatment. In

these high-risk settings, however, it is reasonable to

favour sensitivity in screening for LTBI.

Only five patients could give a definite history

of BCG vaccination. For other patients, such

information was uncertain. While this might reflect

the local clinical situation, it is one of the limitations

of the present study. Despite the mechanistic

similarity, because of the different interpretation

methods employed for the test results and the lack of

comparative trials of the performance of A.TB IGRA

and other IGRAs, the conclusions drawn from the

current study may not be applicable to patients who

are given a different IGRA. Further studies using

individual IGRAs may be warranted to address the

same question.

Conclusion

In arthritis patients in a TB-endemic population,

the level of agreement between TST and A.TB

IGRA for detecting LTBI was only fair. Although

10 mm is the usual cut-off for TST, the level of

agreement between the two tests improved from

fair to moderate when a 5-mm cut-off was used. A

dual testing strategy with TST and IGRA appeared

to be effective and should be pursued, especially

in patients who are prescribed a systemic steroid.

The issue of potential overtreatment is yet to be

evaluated.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interst.

References

1. Furst DE. The risk of infections with biologic therapies for

rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2010;39:327-46. Crossref

2. World Health Organization. Guidelines on the

management of latent tuberculosis infection. Geneva,

Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015.

3. Mok CC. Consensus statements on the indications and

monitoring of anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy

for rheumatic diseases in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Bull

Rheum Dis 2005;5:19-25.

4. Huebner RE, Schein MF, Bass JB Jr. The tuberculin skin

test. Clin Infect Dis 1993;17:968-75. Crossref

5. Matulis G, Jüni P, Villiger PM, Gadola SD. Detection of

latent tuberculosis in immunosuppressed patients with

autoimmune diseases: performance of a Mycobacterium

tuberculosis antigen-specific interferon gamma assay. Ann

Rheum Dis 2008;67:84-90. Crossref

6. Ponce de Leon D, Acevedo-Vasquez E, Alvizuri S, et al.

Comparison of an interferon-gamma assay with tuberculin

skin testing for detection of tuberculosis (TB) infection

in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a TB-endemic

population. J Rheumatol 2008;35:776-81.

7. Song Q, Guo H, Zhong H, et al. Evaluation of a new

interferon-gamma release assay and comparison to

tuberculin skin test during a tuberculosis outbreak. Int J

Infect Dis 2012;16:e522-6. Crossref

8. Ferrara G, Losi M, Meacci M, et al. Routine hospital use

of a new commercial whole blood interferon-gamma assay

for the diagnosis of tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit

Care Med 2005;172:631-5. Crossref

9. Kleinert S, Tony HP, Krueger K, et al. Screening for latent

tuberculosis infection: performance of tuberculin skin

test and interferon-gamma release assays under real-life

conditions. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1791-5. Crossref

10. Mariette X, Baron G, Tubach F, et al. Influence of replacing

tuberculin skin test with ex vivo interferon gamma

release assays on decision to administer prophylactic

antituberculosis antibiotics before anti-TNF therapy. Ann

Rheum Dis 2012;71:1783-90. Crossref

11. Winthrop KL, Weinblatt ME, Daley CL. You can’t always

get what you want, but if you try sometimes (with two

tests—TST and IGRA—for tuberculosis) you get what you

need. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1757-60. Crossref

12. Cao H, Agrawal D, Kushner N, Touzjian N, Essex M,

Lu Y. Delivery of exogenous protein antigens to major

histocompatibility complex class I pathway in cytosol. J

Infect Dis 2002;185:244-51. Crossref

13. McEvers K, Elrefaei M, Norris P, et al. Modified anthrax

fusion proteins deliver HIV antigens through MHC class I

and II pathways. Vaccine 2005;23:4128-35. Crossref

14. Pai M, Zwerling A, Menzies D. Systematic review: T-cell–based assays for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis

infection: an update. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:177-84. Crossref

15. Yilmaz N, Zehra Aydin S, Inanc N, Karakurt S, Direskeneli

H, Yavuz S. Comparison of QuantiFERON-TB Gold test

and tuberculin skin test for the identification of latent

Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in lupus patients.

Lupus 2012;21:491-5. Crossref

16. Lee JH, Sohn HS, Chun JH, et al. Poor agreement between

QuantiFERON-TB Gold test and tuberculin skin test

results for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection in

rheumatoid arthritis patients and healthy controls. Korean

J Intern Med 2014;29:76-84. Crossref

17. Ewer K, Deeks J, Alvarez L, et al. Comparison of T-cell-based assay with tuberculin skin test for diagnosis

of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in a school

tuberculosis outbreak. Lancet 2003;361:1168-73. Crossref

18. Brock I, Weldingh K, Lillebaek T, Follmann F, Andersen P.

Comparison of tuberculin skin test and new specific blood

test in tuberculosis contacts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2004;170:65-9. Crossref

19. Huang YW, Shen GH, Lee JJ, Yang WT. Latent tuberculosis

infection among close contacts of multidrug-resistant

tuberculosis patients in central Taiwan. Int J Tuberc Lung

Dis 2010;14:1430-5.

20. Shalabi NM, Houssen ME. Discrepancy between the

tuberculin skin test and the levels of serum interferon-gamma

in the diagnosis of tubercular infection in contacts.

Clin Biochem 2009;42:1596-601. Crossref

21. Mandalakas AM, Hesseling AC, Chegou NN, et al. High

level of discordant IGRA results in HIV-infected adults

and children. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2008;12:417-23.

22. Shahidi N, Fu YT, Qian H, Bressler B. Performance

of interferon-gamma release assays in patients with

inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18:2034-42. Crossref