Hong Kong Med J 2017 Feb;23(1):35–40 | Epub 2 Dec 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj164899

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Chaperones and intimate physical examinations:

what do male and female patients want?

VC Fan, BSc1;

HT Choy, BSc1;

George YJ Kwok1;

HG Lam1;

QY Lim1;

YY Man1;

CK Tang1;

CC Wong1;

YF Yu1;

Gilberto KK Leung, MB, BS, PhD2

1 Department of Community Medicine, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

2 Department of Surgery, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Gilberto KK Leung (gilberto@hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Many studies of patients’ perception

of a medical chaperone have focused on female

patients; that of male patients are less well studied.

Moreover, previous studies were largely based on

patient populations in English-speaking countries.

Therefore, this study was conducted to investigate

the perception and attitude of male and female

Chinese patients to the presence of a chaperone

during an intimate physical examination.

Methods: A cross-sectional guided questionnaire

survey was conducted on a convenient sample of 150

patients at a public teaching hospital in Hong Kong.

Results: Over 90% of the participants considered

the presence of a chaperone appropriate during

intimate physical examination, and 84% felt that

doctors, irrespective of gender, should always

request the presence of a chaperone. The most

commonly cited reasons included the availability

of an objective account should any legal issue arise,

protection against sexual harassment, and to provide

psychological support. This contrasted with the

experience of those who had previously undergone

an intimate physical examination of whom only

72.6% of women and 35.7% of men had reportedly

been chaperoned. Among female participants,

75.0% preferred to be chaperoned during an

intimate physical examination by a male doctor,

and 28.6% would still prefer to be chaperoned

when being examined by a female doctor. Among

male participants, over 50% indicated no specific

preference but a substantial minority reported a

preference for chaperoned examination (21.2% for

male doctor and 25.8% for female doctor).

Conclusions: Patients in Hong Kong have a high

degree of acceptance and expectations about the

role of a medical chaperone. Both female and male

patients prefer such practice regardless of physician

gender. Doctors are strongly encouraged to discuss

the issue openly with their patients before they

conduct any intimate physical examination.

New knowledge added by this study

- Hong Kong patients have a high degree of acceptance and expectations about the presence of a medical chaperone during an intimate physical examination (IPE), but in actual practice, females and especially male patients are chaperoned less often than they would have preferred.

- A substantial minority (21%-29%) of Hong Kong patients of both genders preferred to be chaperoned for an IPE even when examined by a doctor of the same gender.

- More than a quarter (26%) of male patients preferred to be chaperoned for an IPE when examined by a female doctor.

- Before any IPE, regardless of doctor or patient gender, it is advisable for doctors to ask their patients if they would like to be chaperoned in order to respect for patient preferences.

Introduction

In this current era when personal privacy is highly

regarded, it may seem counterintuitive for patients

to prefer the presence of a third party during an

intimate physical examination (IPE). The presence

of a medical chaperone, however, may offer

comfort and psychological support for patients in

protecting them against indecent behaviour, and is

now an established good practice.1 Conversely, in

an increasingly litigious society, a chaperone may

serve as a witness to protect doctors against false

allegations.2 Usually IPEs involve per-rectal, genital,

or breast examinations, but may also include physical

contact with any other part of the patient’s body.

The majority of reports about patients’

perceptions of a medical chaperone have focused

on female patients3 4 5 6 7; those of male patients are less well studied.8 9 10 A potential discrepancy may exist

between the two groups. Santen et al10 reported

that in the US, a great majority of male

patients (88%) did not care about the presence of a

chaperone, while half of the female patients would

prefer to be chaperoned when examined by a male

physician, and a quarter when examined by a female

doctor. Moreover, previous studies have been largely

based on patient populations in English-speaking

countries. It has been suggested that the presence of

a chaperone is a ‘western concept’ that may receive a

different degree of emphasis or acceptance in other

parts of the world.11 To the best of our knowledge,

there has been no related report on patients in

Hong Kong. In this study, we investigated patients’

attitudes towards and experiences with the presence

of a medical chaperone, and in particular, the

relevant impact of patient and physician gender.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional questionnaire

survey of patients waiting for their consultations

at the Accident and Emergency Department and

the surgical out-patient clinic of a public teaching

hospital over a period of 2 weeks from late February to early March 2015. Participants were recruited irrespective of

age, gender or ethnicity, but were excluded if they

were under 18 years of age, or did not understand

English, Cantonese, or Mandarin. Participants from

the surgical out-patient clinic included both new

and follow-up patients from various subspecialties.

Informed patient consent and approval from the

Institutional Review Board of our institution were

obtained.

Survey instrument

The questionnaire, written in both English

and Chinese, comprised eight questions on

demographics, and 19 questions on previous

experiences with IPE, preferences for the presence

of a chaperone, influence of gender of the examining

physician, and the underlying reasons for their

preferences. Participants selected their answers

from predetermined options. In this study, IPE was

defined as breast, pelvic, genital, and/or per-rectal

examination. This was explained to the participants

at the beginning of the survey. Guidance on the

survey was provided by an investigator if requested

by the participant.

Statistical analyses

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for

the Social Sciences (Windows version 22.0; SPSS

Inc, Chicago [IL], US). Descriptive analyses were

performed on demographic data and participant

responses. Patient ages were grouped into age ranges

(<40, 40-59, and ≥60) for analysis. The independent

variables were patient gender and other demographic

variables (eg age, education level). The dependent

variables were preference for the examining doctor’s

gender, presence of a chaperone with a male

examining doctor, gender of chaperone with a male

examining doctor, presence of chaperone with a

female examining doctor, and gender of chaperone

with a female examining doctor. Bivariate analyses

using the Chi squared test were performed to

compare the various independent variables against

the dependent variables. Other variables based

on participant responses—such as reasons behind

chaperone preferences, previous experience of IPE,

and tendency for litigation if felt harassed—were

analysed against other variables as appropriate.

Statistical significance was set at a probability level

of 0.05.

Results

Participant profile and demographics

Of a convenience sample of 183 patients, 33 declined

to participate and 150 patients were recruited. Of these

patients, 83 (55.3%) were from the Accident and

Emergency Department and 67 (44.7%)

were from surgical out-patient clinics. Recruitment

was done in both locations during the mornings or

afternoons of 23, 24 and 26 February, and 2 and 6

March 2015.

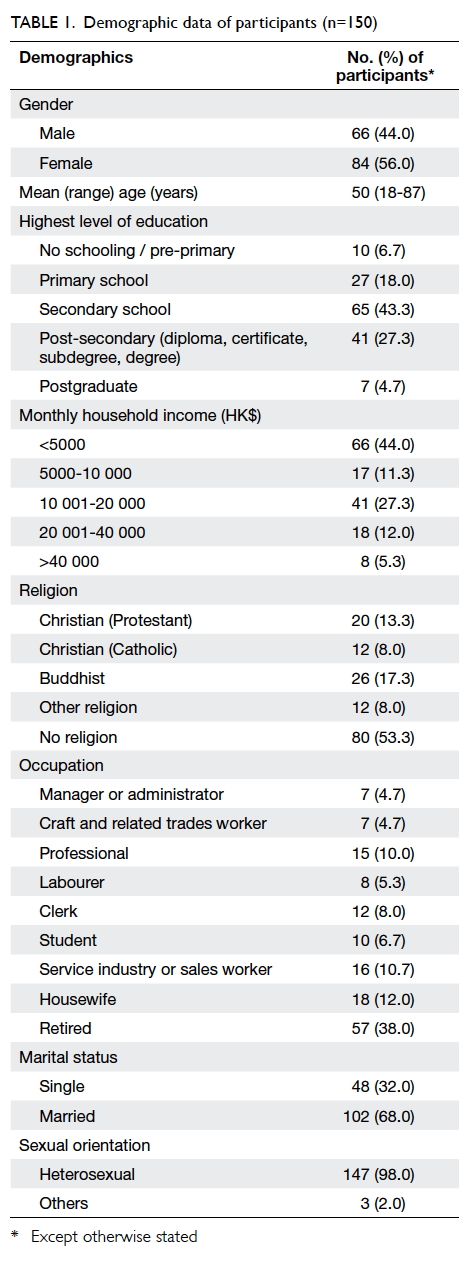

There were similar numbers of women (56.0%)

and men (44.0%). Their mean age was 50 (range,

18-87) years. The majority (75.3%) had completed

a secondary or higher level of education. Over half

(53.3%) were non-religious, and approximately 40%

were retired. The majority of men (63.6%, 42/66)

and women (71.4%, 60/84) were married. Almost all

participants (98.0%, n=147) declared themselves as

heterosexual (Table 1).

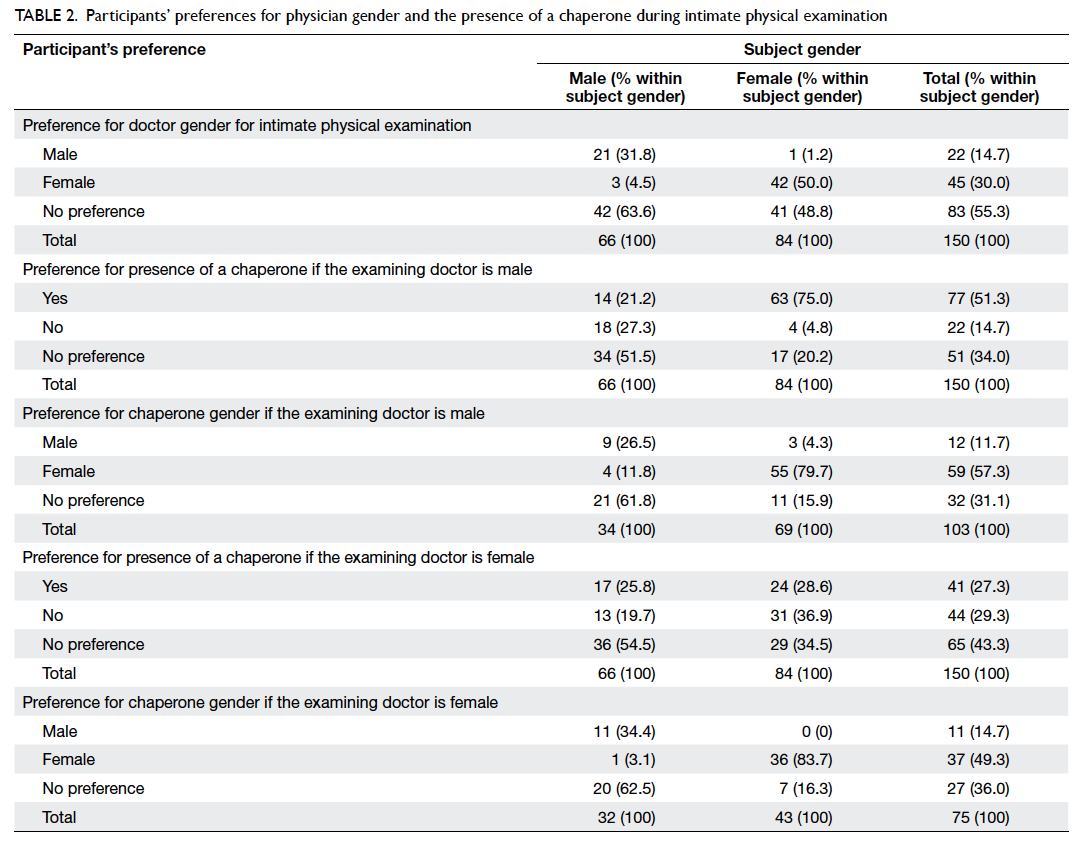

Perception of intimate physical examination and preference for physician gender

In addition to our definitions of IPE, significantly

more women than men also found chest examination

of the respiratory system to be intimate (44.0%,

37/84 women vs 13.6%, 9/66 men; P<0.01). Among

the entire sample, upper limb, lower limb, and

abdominal examinations were also considered to

be intimate by five (3.3%), 14 (9.3%), and 19 (12.7%)

participants, respectively. Overall, 42 (50.0%)

women preferred a female doctor for IPE; only

one (1.2%) preferred a male doctor (Table 2). The

only significant determining factor for women

preferring a female doctor for IPE was the absence

of prior experience of IPE (P=0.04); notable but non-significant

determining factors included younger age

(P=0.09) and being unmarried (P=0.10). For men, 42

(63.6%) participants did not have any preference for

physician gender and 21 (31.8%) would prefer a male

doctor (Table 2). No significant determining factors

for men preferring either a male or female doctor for

IPE were identified.

Table 2. Participants’ preferences for physician gender and the presence of a chaperone during intimate physical examination

Previous experiences of intimate physical

examination and general preferences for

chaperoned examination

Of the 150 participants, 115 (76.7%) reported

previous experience of IPE: 42 were men (63.6%

of male participants) and 73 were women (86.9%

of female participants). A large majority (90.7%,

136/150) of the participants considered the

presence of a chaperone appropriate during IPE,

and 84.0% (126/150) felt that doctors, irrespective of

gender, should always ask if the patient would like

a chaperone. This contrasted with the experience

of those who had had previous IPE of whom only

72.6% (53/73) of women and 35.7% (15/42) of men

reported having been chaperoned. For those whose

previous IPE was unchaperoned, 75.0% (15/20) of

women and 44.4% (12/27) of men would actually

prefer to be chaperoned. Interestingly, participants

with prior experience of IPE, irrespective of gender,

were significantly more likely to want a chaperone

when examined by a male doctor (57.4% with vs

28.6% without; P<0.01) but not a female doctor

(28.7% with vs 25.7% without; P=0.87) when

compared with those with no such experience. Most

participants (72.7%, 109/150) regarded health care

workers as suitable chaperones, and 52.7% (79/150)

would also consider a family member, and 20.0%

(30/150) a friend to be appropriate.

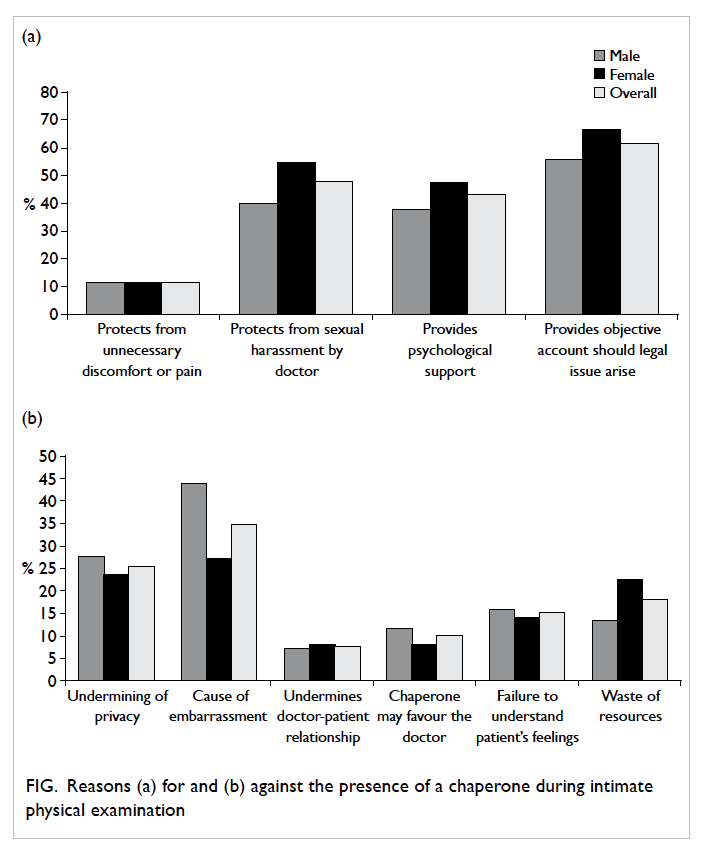

The most commonly cited reasons for

preferring a chaperone included the availability of an

objective account should any legal issue arise (61.3%,

92/150), protection against sexual harassment

by the doctor (48.0%, 72/150), and psychological

support (43.3%, 65/150) [Fig a]. The most commonly cited reasons for not having a chaperone included

embarrassment (34.7%, 52/150); significantly more

men (43.9%, 29/66) than women (27.4%, 23/84)

considered a chaperone’s presence embarrassing

(P=0.03). Furthermore, 26.0% of the participants

(39/150) felt that the presence of a chaperone would

undermine their privacy (Fig b).

Figure. Reasons (a) for and (b) against the presence of a chaperone during intimate physical examination

Women’s preferences for chaperoned

intimate physical examination

The majority of women (75.0%, 63/84) would prefer

a chaperone to be present when being examined

by a male doctor, and 79.7% (55/69) of female

respondents preferred that chaperone to be female

(Table 2). Even when being examined by a female doctor, 28.6% (24/84) would still prefer to be

chaperoned (Table 2). Women aged between 40 and 59 years were significantly more likely than other

age-groups to prefer chaperoned IPE when examined

by a female doctor (P=0.04). Other demographic

factors—including education level, income, religion

and marital status—were not significantly associated

with any particular preferences.

Men’s preferences for chaperoned intimate

physical examination

More than half of the men had no specific preference,

regardless of physician gender. There was, however,

a proportion who would want to be chaperoned

when examined by a male (21.2%, 14/66) or female

(25.8%, 17/66) doctor (Table 2). Men who wished to be chaperoned when examined by a male doctor

were significantly more likely to also prefer being

chaperoned when examined by a female doctor

(P<0.01). Of note is that a great majority of the men

who preferred chaperoned IPE when examined by a

male doctor indicated that chaperones could provide

an objective account should a legal issue arise

(85.7%, 12/14). There were no significant differences

in terms of demographic variables between the ‘no

preference’, ‘no chaperone’, and ‘prefer chaperone’

groups, regardless of the examining doctor’s gender.

Discussion

Our results highlighted the different views of male

and female subjects in this locality. The majority of

our female patients would prefer to be chaperoned

when examined by a male doctor, and previous

experience of IPE appeared to enforce such a

tendency. This finding is consistent with those from

other countries.4 8 12 Interestingly, and somewhat

unexpectedly, a substantial minority of women would

still prefer to be chaperoned when examined by a

female doctor. Another noteworthy finding was that

male participants who preferred a chaperoned IPE

by a male doctor would also hold a similar preference

when examined by a female doctor, and that their

most commonly cited reason was the availability of

an objective account in case of medicolegal disputes.

This was despite concerns about personal privacy

and feelings of embarrassment.

Our findings compare well with the situation

in the United Kingdom13 and Australia14 where the majority of patients were aware of and would prefer

the practice. When compared with a similar study

conducted at the Emergency Department in the

US, however, we found that patients in

Hong Kong were more likely to prefer chaperoned

IPE when examined by a doctor of the opposite sex

(male patient–female doctor: 25.8% vs 2-3%; female

patient–male doctor: 75% vs 45-47%).3 Other studies

found that physician gender had a variable impact

on female patient’s preference for a chaperone.10

Our findings suggest a generally higher degree of

acceptance of, if not expectation for, the presence

of a medical chaperone in Hong Kong, although

differences in study setting, subject profile, and

study definitions of IPE limit the validity of such

comparisons.

The reported experiences of participants

who have had previous IPE indicate that their

expectations have not been met on a number of

occasions. Several reasons have been suggested

for the inadequate use of chaperones including,

inter alia, the shortage of nursing staff to act as

chaperones,15 and a general lack of awareness.16 This is certainly an area for improvement in our health

care setting. In this regard, it is important to note

that some patients would also consider examinations

of the abdomen and limbs to be intimate, and that

chaperones may still be preferred even when the

physician and patient are of the same gender. The

Code of Professional Conduct issued by the Medical

Council of Hong Kong states that ‘an intimate

examination of a patient is recommended to be

conducted in the presence of a chaperone to the

knowledge of the patient’.17 ‘Intimate examination’ is

not defined and there is no advice about the impact

of gender. The United Kingdom General Medical Council (GMC)

guidelines nonetheless specify that IPE may include

‘any examination where it is necessary to touch or

even be close to the patient’, and the requirement for

a chaperone should apply whether or not the patient

and doctor are of the same or opposite gender.1

Challenging situations may arise when there is

a shortage of staff or when the patient refuses the

presence of a chaperone. The GMC have provided

some detailed guidance.1

Our study has several limitations. First, the

number of participants was relatively small and our

findings may not be readily generalisable, particularly

outside the public hospital setting, where patients are

likely to be more familiar with their doctor and have

more control over which doctor sees and examines

them. The convenient sampling method that we

adopted may result in systematic bias, skewed

results, and potentially suboptimal generalisability

of our findings. Second, our definition of IPE

encompassed a range of different examinations, and

it might be possible that participants have different

preferences regarding each type. Third, our cohort

consisted of relatively few young subjects (only 15%

were aged <30 years) and this might have affected

our ability to demonstrate any impact of age. Last,

as to the reasons for participants’ preferences, our

questionnaire only provided a short list of options

rather than an open question and this could have

limited the range of responses. Future studies may

focus on patient’s preferences in specific settings

(eg primary care) as well as physician’s practice in

order to inform and promote public and professional

awareness in Hong Kong.

Conclusions

Patients in Hong Kong have a high degree of

acceptance towards the presence of a medical

chaperone. Both female and male patients prefer

such practice regardless of physician gender although

individual patients may value the practice differently.

Doctors are strongly encouraged to discuss the issue

openly with their patients and offer the presence of

a chaperone prior to any IPE; an alternative would

be to put up a sign asking patients to notify the

doctor or other staff if they prefer the presence of a

chaperone during IPE.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. General Medical Council. Good medical practice (2013).

Available from: http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/good_medical_practice.asp. Accessed 27 Nov 2015.

2. Wai D, Katsaris M, Singhal R. Chaperones: are we

protecting patients? Br J Gen Pract 2008;58:54-7. Crossref

3. Buchta RM. Adolescent females’ preferences regarding use

of a chaperone during a pelvic examination. Observations

from a private-practice setting. J Adolesc Health Care

1986;7:409-11. Crossref

4. Patton DD, Bodtke S, Homer RD. Patient perceptions of

the need for chaperones during pelvic exams. Fam Med

1990;22:215-8.

5. Fiddes P, Scott A, Fletcher J, Glasier A. Attitudes towards

pelvic examination and chaperones: a questionnaire survey

of patients and providers. Contraception 2003;67:313-7. Crossref

6. Simanjuntak C, Cummings R, Chen MY, Williams H, Snow

A, Fairley CK. What female patients feel about the offer of

a chaperone by a male sexual health practitioner. Int J STD

AIDS 2009;20:165-7. Crossref

7. Sinha S, De A, Jones N, Jones M, Williams RJ, Vaughan-Williams E. Patients’ attitude towards the use of a

chaperone in breast examination. Ann R Coll Surg Engl

2009;91:46-9. Crossref

8. Penn MA, Bourguet CC. Patients’ attitudes regarding

chaperones during physical examinations. J Fam Pract

1992;35:639-43.

9. Osmond MK, Copas AJ, Newey C, Edwards SG, Jungmann

E, Mercey D. The use of chaperones for intimate

examinations: the patient perspective based on an

anonymous questionnaire. Int J STD AIDS 2007;18:667-71. Crossref

10. Santen SA, Seth N, Hemphill RR, Wrenn KD. Chaperones

for rectal and genital examinations in the emergency

department: what do patients and physicians want? South

Med J 2008;101:24-8. Crossref

11. Van Hecke O, Jones K. The use of chaperones in general

practice: Is this just a ‘Western’ concept? Med Sci Law

2015;55:278-83. Crossref

12. Teague R, Newton D, Fairley CK, et al. The differing views

of male and female patients toward chaperones for genital

examinations in a sexual health setting. Sex Transm Dis

2007;34:1004-7. Crossref

13. Pydah KL, Howard J. The awareness and use of chaperones

by patients in an English general practice. J Med Ethics

2010;36:512-3. Crossref

14. Baber JA, Davies SC, Dayan LS. An extra pair of eyes: do

patients want a chaperone when having an anogenital

examination? Sex Health 2007;4:89-93. Crossref

15. Price DH, Tracy CS, Upshur RE. Chaperone use during

intimate examinations in primary care: postal survey of

family physicians. BMC Fam Pract 2005;6:52. Crossref

16. Vogel L. Chaperones: friend or foe, and to whom? CMAJ

2012;184:642-3. Crossref

17. Medical Council of Hong Kong. Code of Professional

Conduct. 2009. Available from: http://www.mchk.org.hk/Code_of_Professional_Conduct_2009.pdf. Accessed 30

Aug 2015.