DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144390

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Babesiosis acquired from a pet dog: a second reported case in Hong Kong

Jacky MC Chan, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine); KY Tsang, FHKAM (Medicine), FRCP (Glasg & Edin);

Thomas SH Chik, MB, ChB, MRCP(UK); WS Leung, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine); Owen TY Tsang, FHKAM (Medicine), FRCP (Edin)

Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Princess Margaret Hospital, Laichikok, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Jacky MC Chan (cmc061@ha.org.hk)

A 61-year-old Chinese man was admitted to our

hospital in June 2012 with a 2-week history of fever

and chills. After admission, he developed hypotension

and respiratory distress and was transferred to the

intensive care unit (ICU) for further management.

He frequently commuted between New York,

Hong Kong, and Shanghai for business. He lived in

his own house in New York and had a dog. Three

weeks before onset of his symptoms, he swept his

basement where his dog spent most of its time. He

was not aware of any tick bite.

He was a chronic smoker but enjoyed good past

health. His symptoms began with fever and chills

while in China. He also experienced malaise and a

mild dry cough. He had no skin rash, or abdominal or

urinary symptoms. A diagnosis of upper respiratory

tract infection was made and he was given a course

of piperacillin-tazobactam during hospitalisation

in China. Symptoms persisted, however, and he

presented to a public hospital in Hong Kong. Initial

blood tests revealed a normochromic normocytic

anaemia (haemoglobin, 81 g/L) with reticulocytosis,

marked thrombocytopenia, and moderate renal

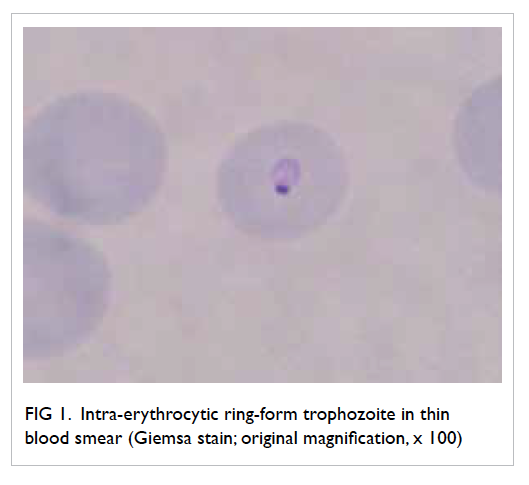

impairment. Blood smear revealed the presence of

intra-erythrocytic ring-form parasites, suggestive

of Plasmodium falciparum infection (Fig 1). Chest

X-ray showed bilateral extensive abnormal lung

infiltrates. He was transferred to our hospital for

further management.

Figure 1. Intra-erythrocytic ring-form trophozoite in thin blood smear (Giemsa stain; original magnification, x 100)

He soon developed shock and was

transferred to the ICU. Further blood tests revealed

hyperbilirubinaemia and evidence of haemolysis.

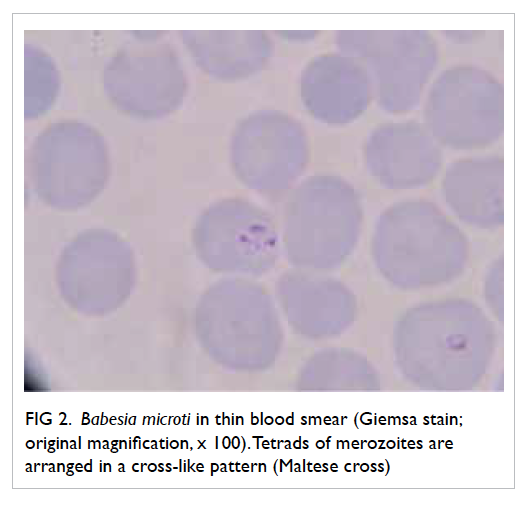

Peripheral blood smear for malaria was repeated

and revealed 3.8% parasitised red cells. Pleomorphic

ring forms were noted, with occasional arrangement

in a cross-like pattern (Fig 2). Rapid antigen test for P falciparum was negative and this raised the

suspicion of babesiosis. A subsequent blood Babesia

microti polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was

positive and a diagnosis of babesiosis was confirmed.

Figure 2. Babesia microti in thin blood smear (Giemsa stain; original magnification, x 100). Tetrads of merozoites are arranged in a cross-like pattern (Maltese cross)

Quinine and clindamycin were initiated. The

patient experienced severe tinnitus after 5 days of

treatment and quinine was stopped. Doxycycline

was added for treatment due to persistent fever

and because it is known that Lyme’s disease can be

a concurrent infection. He stayed in the ICU for 6

days and his condition was stabilised with resolution

of fever. Blood smear for Babesia turned negative on

day 14 of treatment. Supportive blood transfusion

was given for anaemia and the patient was discharged

after 21 days.

He attended regular follow-ups in our clinic.

Repeated blood smear for babesiosis and Babesia

PCR test (in September 2012, 3 months after

treatment) were negative. He had the basement of

his New York apartment professionally cleaned and

had his dog treated for ticks.

Discussion

This is the second imported case of human babesiosis

in Hong Kong since 2007.1 Babesiosis is a tick-borne

disease in which patients are infected with intra-erythrocytic

parasites of the genus Babesia. The

common species affecting humans are B microti and

Babesia divergens, mostly found in the United States

and Europe, respectively. White-footed mice are

the primary reservoir host, but other small rodents

may also carry B microti. The Babesia parasites are

transmitted to humans accidentally by Ixodid tick

bites. In the United States, Ixodes scapularis is the

most common vector. The ticks become infected

with B microti when they feed on vertebrate reservoir

hosts such as infected white-footed mice and white-tailed

deer. Humans are usually accidental hosts.2

The diagnosis of human babesiosis is made by

microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained thick

and thin blood smears. Microscopically, Babesia

species may appear as round or oval-shaped forms,

with blue cytoplasm and red chromatin. Multiple

parasites may be present in a single-infected red

blood cell. Differentiation of the ring-form of

Babesia species and P falciparum may be difficult.

Some distinguishing features of babesiosis include

the presence of extra-erythrocytic forms in severe

cases and the absence of pigment deposits typically

seen in older ring stages of P falciparum. The Maltese

cross pattern in which tetrads of merozoites are

arranged is pathognomonic of babesiosis, but they

are not commonly seen.3 Nonetheless, the different

species of babesiosis cannot be distinguished by

microscopic examination. Real-time PCR performed

on DNA targeting the 18S rRNA gene of B microti

is therefore a more specific and accurate method to

detect B microti.4

Our patient was a case of possible pet-associated

human Babesia infection. Babesiosis is a

zoonotic protozoan disease of medical, veterinary,

and economic importance. A case of human

babesiosis acquired from a pet dog has been reported

where the dog was heavily infested with ticks.5 In a

Brazilian evaluation of ectoparasites in dogs kept

in apartments, Ixodid nymphs were found in 2%.

In houses with grassy yards, 18% of pet dogs were

found to carry Ixodid nymphs.6 Different species of

Ixodid ticks have been identified in dogs, with the

head being the most common site of attachment.

The activity of tick attachment peaks in spring

and in autumn. Canine babesiosis is diagnosed by

veterinarians in approximately 20% of tick-infested

dogs.7 In one study in New York state, I scapularis

ticks were collected from recreational lands to

determine the prevalence and distribution of tick-borne

pathogens. The overall prevalence of B microti

was approximately 3% among both nymphs and

adult ticks.8

In Hong Kong, around 250 000 households

are estimated to keep dogs or cats, representing

10.6% of all households.9 There has been no single

reported case of human babesiosis in Hong Kong

although the disease is common in the cat and

dog population. Recently a new Babesia species,

Babesia hongkongensis has been identified in the

feline population.10 The prevalence of this new local

species is low among free-roaming cats in Hong

Kong and the pathogenicity in pet cats is unknown.

The clinical presentation of human babesiosis

varies. Infected patients may present with a mild-to-moderate viral-like illness, with gradual onset of

chills, sweats, headache, arthralgia, and anorexia.

Some patients present with a prolonged course of

pyrexia of unknown origin. Physical examination

may reveal mild splenomegaly or hepatomegaly.

Severe infection generally occurs in those with

an underlying immunosuppressed condition,

particularly patients with previous splenectomy.

Complications of babesiosis include acute respiratory

failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation,

and multi-organ failure.3

Combination therapy with atovaquone and

azithromycin is the treatment of choice for mild-to-moderate Babesia infection. In severe cases, the

use of clindamycin and quinine is recommended.

In general, the combination of atovaquone and

azithromycin is better tolerated with fewer adverse

effects.11 All doses of antimicrobial therapy

are administered for 7 to 10 days. For severely

immunocompromised patients with persistent

relapsing infection, a longer duration of at least 6

weeks’ treatment is recommended, continuing for

2 weeks after blood smears become negative for

Babesia. For fulminant cases, exchange transfusion

may be required.2 12

References

1. Wong WS, Chung JY, Wong KF. Images in haematology.

Human babesiosis. Br J Haematol 2008;140:364. Crossref

2. Vannier E, Krause PJ. Human babesiosis. N Engl J Med

2012;66:2397-407. Crossref

3. Vannier E, Gewurz BE, Krause PJ. Human babesiosis.

Infect Dis Clin North Am 2008;22:469-88, viii-ix. Crossref

4. Teal AE, Habura A, Ennis J, Keithly JS, Madison-Antenucci

S. A new real-time PCR assay for improved detection of

the parasite Babesia microti. J Clin Microbiol 2012;50:903-8. Crossref

5. EL-Bahnasawy MM, Khalil HH, Morsy TA. Babesiosis

in an Egyptian boy acquired from pet dog, and a general

review. J Egypt Soc Parasitol 2011;41:99-108.

6. Soares AO, Souza AD, Feliciano EA, Rodrigues AF,

D’Agosto M, Daemon E. Evaluation of ectoparasites and

hemoparasites in dogs kept in apartments and houses with

yards in the city of Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais, Brazil [in

Portuguese]. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2006;15:13-6.

7. Földvári G, Farkas R. Ixodid tick species attaching to dogs

in Hungary. Vet Parasitol 2005;129:125-31. Crossref

8. Prusinski MA, Kokas JE, Hukey KT, Kogut SJ, Lee

J, Backenson PB. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi

(Spirochaetales: Spirochaetaceae), Anaplasma

phagocytophilum (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae), and

Babesia microti (Piroplasmida: Babesiidae) in Ixodes

scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) collected from recreational

lands in the Hudson Valley Region, New York State. J Med

Entomol 2014;51:226-36. Crossref

9. Thematic Household Survey Report No. 48. Census and

Statistics Department, Hong Kong SAR Government 2011. Available from: http://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B11302482011XXXXB0100.pdf. Accessed Feb 2016.

10. Wong SS, Poon RW, Hui JJ, Yuen KY. Detection of Babesia

hongkongensis sp. nov. in a free-roaming Felis catus cat in

Hong Kong. J Clin Microbiol 2012;50:2799-803. Crossref

11. Krause PJ, Lepore T, Sikand VK, et al. Atovaquone and

azithromycin for the treatment of babesiosis. N Engl J Med

2000;343:1454-8. Crossref

12. Dorman SE, Cannon ME, Telford SR 3rd, Frank KM,

Churchill WH. Fulminant babesiosis treated with

clindamycin, quinine, and whole-blood exchange

transfusion. Transfusion 2000;40:375-80. Crossref