Hong Kong Med J 2016 Jun;22(3):263–9 | Epub 6 May 2016

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154645

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REVIEW ARTICLE CME

Common urological problems in children: prepuce, phimosis, and buried penis

Ivy HY Chan, FRCSEd(Paed), FHKAM (Surgery);

Kenneth KY Wong, PhD, FHKAM (Surgery)

Division of Paediatric Surgery, Department of Surgery, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Kenneth KY Wong (kkywong@hku.hk)

Abstract

Parents often bring their children to the family

doctor because of urological problems. Many

general practitioners have received little training in

this specialty. In this review, we aimed to provide

a concise and informative review of common

urological problems in children. This review will

focus on the prepuce.

Introduction

Young boys are often brought by parents to see a

medical practitioner for ‘phimosis’, and circumcision

is one of the most commonly performed operations.

Yet this topic is often not taught routinely in medical

school. Buried penis is another less well-defined

condition. In this review article, we will describe

these conditions in a more systematic manner and

present the current available knowledge about the

conditions and management options.

Normal development of the prepuce and phimosis

Phimosis generally refers to a condition where the

prepuce cannot be withdrawn to expose the glans.

True phimosis, however, should be defined as a

pathological condition in which the prepuce is

scarred, non-retractile, and with a narrow preputial

ring. This is secondary to balanitis xerotica obliterans

(BXO). To avoid confusion of the terms, ‘physiological

phimosis’ and ‘pathological phimosis’ should be

used.

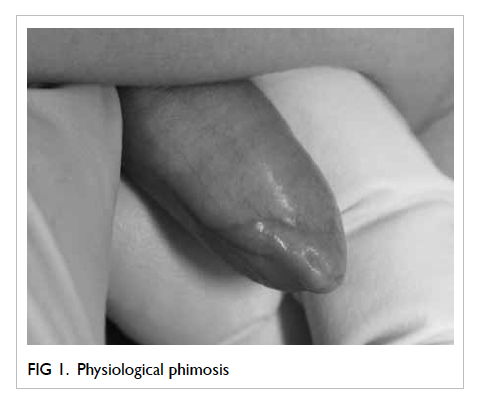

Physiological phimosis

Physiological phimosis is a natural condition in

which the prepuce cannot be retracted and there is

natural adhesion between the glans and the prepuce

(Fig 1). Almost all normal male babies are born

with a non-retractable foreskin. Indeed, Gairdner1

noticed only 4% of newborns in England and Wales

had retractable foreskin. The foreskin becomes

retractable as the child grows. The adhesion between

the prepuce and glans will also separate gradually

as a spontaneous biological process.2 3 4 By the age

of 3 years, 90% of prepuces are retractable.1 Øster2 examined preputial development in 173 Danish

boys aged 6 to 17 years annually for 7 years and

determined that the foreskin was non-retractable

in 8% of young boys but in only 1% at 17 years of

age. Similar findings were noted in Chinese boys by

Ko et al5 and Hsieh et al,6 who reported 84.1%5 and

58.1%6 of boys with a completely retractable prepuce

by the age of 13 years. Both the retractability and

the shape of the prepuce lie within a spectrum that

can sometimes be difficult to describe and there is

no agreed classification system. Different papers

have used their own classifications for the purpose

of study. One example was the study by Kayaba et

al3 in which retractability was graded according to

how much of the glans was visible after prepuce

retraction.

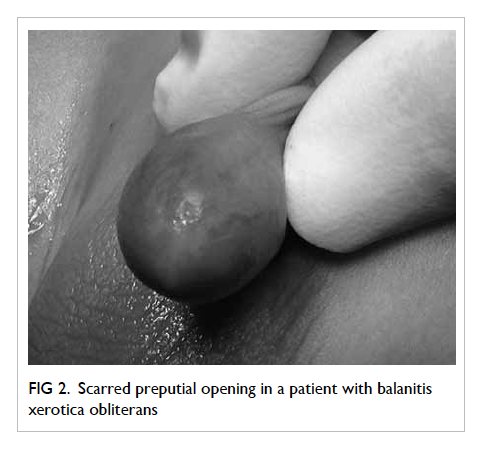

Pathological phimosis/balanitis xerotica obliterans

Balanitis xerotica obliterans is a chronic and

progressive inflammatory condition that affects the

prepuce, glans, and sometimes the urethra (Fig 2).

It was first described in 1928 by Stühmer.7 There

are three components of this condition: ‘balanitis’,

meaning chronic inflammation of the glans penis;

‘xerotica’, an abnormally dry appearance of the lesion;

and ‘obliterans’, for the association of occasional

endarteritis.

The aetiology and the true incidence is

unknown. An incidence of 0.6% has been reported

for boys affected by their 15th birthday.8 It is

suspected clinically when there is a ring of hardened

tissue with a whitish colour at the tip of the foreskin.

There are also other clinical features such as white

patches over the glans, perimeatal sclerotic changes,

or meatal stenosis. It can cause urethral stricture and

retention of urine.

Medical students are not taught about

the condition and it is generally not diagnosed at the

primary care level. Gargollo et al9 reviewed 41

patients with the pathologically confirmed diagnosis

of BXO at their centre and confirmed that no patient

had the diagnosis at referral. Pathology of the

excised prepuce showed lymphocytic infiltration in

the ripper dermis, hyalinosis and homogenisation

of collagen, basal cell vacuolation, atrophy of the

stratum malpighii, and hyperkeratosis.

Potential clinical problems

Parents often seek medical advice about their son’s

‘foreskin problems’. Pain, redness, itchiness, long

prepuce, ballooning during urination, difficulty in

retracting the prepuce, and penis being too short

are the common complaints. Before answering all

the questions, we should be able to differentiate the

normal and abnormal.

Pain, pruritus, smegma

Most parents may think that the presence of pain or

pruritus indicates infection of the prepuce, and yet

poor prepuce hygiene is a more common problem.

Smegma is another common complaint from

parents, usually described as a ‘mass’, or ‘white pearl’.

Smegma can be identified by gently retracting the

prepuce (Fig 3). It is harmless and is a combination

of secretions and desquamated skin.

Difficulty in retracting the prepuce and long prepuce

Difficulty in retracting the prepuce and long prepuce

is a feature of physiological phimosis. This is normal

in most boys and requires no attention apart from

daily routine prepuce hygiene. The role of the

physician is to differentiate normal and abnormal

prepuce, then guide proper management.

Ballooning

Ballooning is a feature of a tight prepuce. Because

of the tight preputial opening, there is dilatation of

the preputial sac during voiding. This causes a lot

of parental anxiety about possible urinary outflow

obstruction. Babu et al10 performed uroflow studies

in boys with and without ballooning of the foreskin

and determined that there was significant difference.

Balanoposthitis

This refers to inflammation of the glans (balanitis)

and the foreskin (posthitis) [Fig 4]. Patients present

with a swollen prepuce with or without discharge

from the preputial opening. It is a relatively

common condition, with a reported incidence of

6% in uncircumcised boys.11 In the absence of fever,

underlying urinary tract infection (UTI) is unlikely.

Simple bathing and rinsing with normal saline or

chlorhexidine gluconate solution after urination is

sufficient treatment for afebrile patients. Topical

antibiotic cream is commonly prescribed for local

infection. Serious conditions and presence of fever

may warrant further investigations, oral antibiotics,

or even hospital admission.

Clinical management of phimosis

Prepuce hygiene and retraction

After diagnosing physiological phimosis, parents

should be taught how to keep the prepuce clean.

Only a small proportion of parents know what is

required.12 Gentle daily retraction of the prepuce

and rinsing of the prepuce with warm water can

maintain good hygiene and prevent infection.

Parents should also be taught to avoid forcible

retraction of the prepuce.13 14 15 Simple stretching of

the prepuce alone has been shown to be effective

in achieving complete resolution of physiological

phimosis.16 After 3 months of prepuce stretching,

76% of patients reported resolution of phimosis.16

Topical steroids

Topical steroids have been prescribed in the

treatment of phimosis. Their anti-inflammatory,

immunosuppressive, and skin-thinning properties

are believed to be the mechanism for resolution of

phimosis.17 Their use in physiological phimosis was

first described by Kikiros et al.18 Subsequent studies

showed the response rate for resolution of phimosis

to be 68.2% to 95%.16 19 20 21 22 Moreno et al23 subsequently

performed a meta-analysis and reviewed 12

randomised controlled trials on the use of different

topical steroid formulations, and again confirmed the

significant benefit of corticosteroids in the complete

or partial clinical resolution of phimosis (risk

ratio=2.45; 95% confidence interval, 1.84-3.26).

Parents often ask about the potential

complications of topical steroid use. Golubovic et al24

and Pileggi et al25 addressed this issue by measuring

serum cortisol levels and salivary cortisol levels,

respectively. Neither could demonstrate a significant

change in cortisol level after application of topical

steroids. Topical steroid therapy is thus a safe and

effective alternative to circumcision.

Circumcision

Circumcision is a procedure in which part of the

foreskin is removed and results in a non-covered glans.

It is a procedure that has been described for many

years and is performed almost universally in Jewish

and Muslim boys. The rate of newborn circumcision

is high in the US (>50%),26 27 but routine circumcision is not a tradition in the Chinese population. Leung et

al28 showed the circumcision rate in 6- to 12-year-old

boys in Hong Kong to be 10.7%.

Benefits versus risks of circumcision

There is evidence that circumcision can reduce the

risk of UTI, penile cancer, human immunodeficiency

virus (HIV), and sexually transmitted disease (STD).

Urinary tract infection

Childhood UTI is associated with renal scarring. The

symptoms and signs of UTI are often non-specific in

young children who may present with fever alone. The

overall prevalence of UTI in children with fever (<19

years old) was reported to be 7.8% in a meta-analysis

published in 2008.29 The pooled prevalence of febrile

UTI in male infants from 0 to 24 months of age was

8.0% (confidence interval, 5.5-10.4%). Circumcised

boys had a lower risk of developing UTI—20.1% in

uncircumcised versus 2.4% in circumcised infants of

less than 3 months of age with fever.29

Another systematic review in 2005 showed

a decreased risk of UTI in circumcised boys.30 The

authors calculated the number-needed-to-treat was

111 in normal boys, but the number-needed-to-treat

for recurrent UTI and high-grade vesicoureteric

reflux was 11 and 4, respectively. It was evident that

the benefits of circumcision were higher for boys at

risk of UTI.

Sexually transmitted infection and human immunodeficiency virus

Three randomised controlled trials concluded that

adult circumcision had a protective effect against

acquisition of HIV.31 32 33 Although the full mechanism

of protection was not fully understood, it was

shown that the inner foreskin harbours epithelial

CD4+ CCR5+ cells and has features of an inflamed

epidermal barrier. These changes may support a

subclinical inflammatory state in uncircumcised

men, with availability of target cells for HIV

infection, and potentially account for the benefits of

circumcision in STD prevention.34 All the trials were

performed in Africa, with a much higher prevalence

of HIV. Education about use of condoms and safe

sex practice was relatively primitive compared with

Hong Kong. Readers should therefore interpret these

results with caution when discussing the benefits of

circumcision on HIV prevention with our patients.

A meta-analysis published in 2006 by Weiss

et al35 showed that circumcised males were at

a lower risk of syphilis, and there was a lower

association with herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2. Other cohorts also showed similar findings,

with circumcised males having a decreased risk of

syphilis, gonorrhoea, and human papillomavirus

(HPV).36 37 38 39 On the contrary, another systematic

review by Van Howe40 showed that most STDs are

not impacted significantly by circumcision status.

They included chlamydia, gonorrhoea, HSV, and

HPV. Despite the positive findings in some studies,

it should be remembered that the use of a condom

and safe sex are the most important deterrents. The

protective effect of circumcision might give a false

sense of security and should not be advocated over

other preventive measures.

Risks and complications of circumcision

Circumcision is one of the most commonly

performed operations in the world and involves

excision of a ring of preputial tissue. In general, the

procedure may involve the use of a special device

(eg Plastibell, Gomco clamp, Mogen clamp, Shang

ring) or may apply the ‘free hand excision method’.

Depending on the method, suturing may or may not

be involved. Every procedure is associated with risks

and complications. The rate is different depending

on the operator (ritual circumciser or surgeon) and

the setting (home, clinic, or hospital).

There has been inadequate comparison of the

complication rates of ‘device method’ surgery and

the ‘free hand excision method’ so it is difficult for

the authors to recommend a single best method

for surgical circumcision. The overall complication

rate of circumcision varies from 0.5%41 to 8%.42 As the indication for circumcision in some patients is

not medical (eg religious or ritual circumcision), the

risks should be carefully explained to the patient

before the procedure.

Early complications include bleeding, wound

infection, and UTI. Bleeding is one of the most

common postoperative complications that, in

extreme cases, may lead to shock.43 Meticulous

technique during the procedure is thus important.

If bleeding is encountered postoperatively, it can

usually be controlled by local compression or

bedside plication.

In a UK study, the infection rate after

circumcision has been reported to be around

0.3%.44 It is usually minor and can be treated by

simple irrigation with antiseptic solution. Systemic

antibiotics are rarely needed. A systematic review of

the prevalence and complications of circumcision

was performed in eastern and southern Africa.45

The infection rate was very high and two thirds of

patients presented with systemic infection requiring

antibiotics. The authors believe the quality of local

wound care is very important in minimising the

infection rate. Urinary retention is uncommon after

circumcision but can occur in up to 3.6% of cases.

It is likely to be pain-related or due to improper

placement of a circumcision device, eg Plastibell.46

Wound dehiscence may occur and can be

managed with wound care and dressing. Very rarely,

excessive prepuce loss as a result of excessive skin

excision may be seen. This potentially disastrous

complication has been reported to be treated with a

full-thickness skin graft.47

Late complications are not uncommon,

reported by one study to be present in 4.7% of

newborn circumcisions.48 Redundant residual skin

and recurrent penile adhesion are the two most

common late complications that may necessitate

revision circumcision. Meatal stenosis is another

late but uncommon complication after circumcision

and requires surgery. The cause is not known but it

is more common in patients with BXO.49 50

There are some other less-common but severe

complications, including urethrocutaneous fistula,

glans amputation, and iatrogenic buried penis.51 52 These have long-term physiological and psychological

consequences for both the patient and family.

Surgical technique and the surgeon’s awareness

of limitations of each method of circumcision is

important. Parents should be fully informed before

they make a decision about circumcision, especially

where the patient is physically weak or where there

is no medical indication for the procedure.

Current guidelines on circumcision

Various international colleges have produced

guidelines on circumcision. These include the

British Association of Paediatric Surgeons,53 the

Royal Australasian College of Physicians,54 and the

American Academy of Pediatrics.55 56

Having taken all these into account, the overall

view of our unit is as follows:

(1) Although there is some scientific evidence for the benefits of circumcision, the routine use on all males is not justified. Parents should be fully informed of all the potential benefits and risks of the procedure.

(2) Our current medical indications for circumcision are:

(a) penile malignancy (though this is extremely rare in children) or traumatic foreskin injury where it cannot be salvaged; and

(b) BXO, severe recurrent attacks of balanoposthitis, and/or recurrent febrile UTIs.

(3) Non-therapeutic ‘ritual’ circumcision may be offered.

(1) Although there is some scientific evidence for the benefits of circumcision, the routine use on all males is not justified. Parents should be fully informed of all the potential benefits and risks of the procedure.

(2) Our current medical indications for circumcision are:

(a) penile malignancy (though this is extremely rare in children) or traumatic foreskin injury where it cannot be salvaged; and

(b) BXO, severe recurrent attacks of balanoposthitis, and/or recurrent febrile UTIs.

(3) Non-therapeutic ‘ritual’ circumcision may be offered.

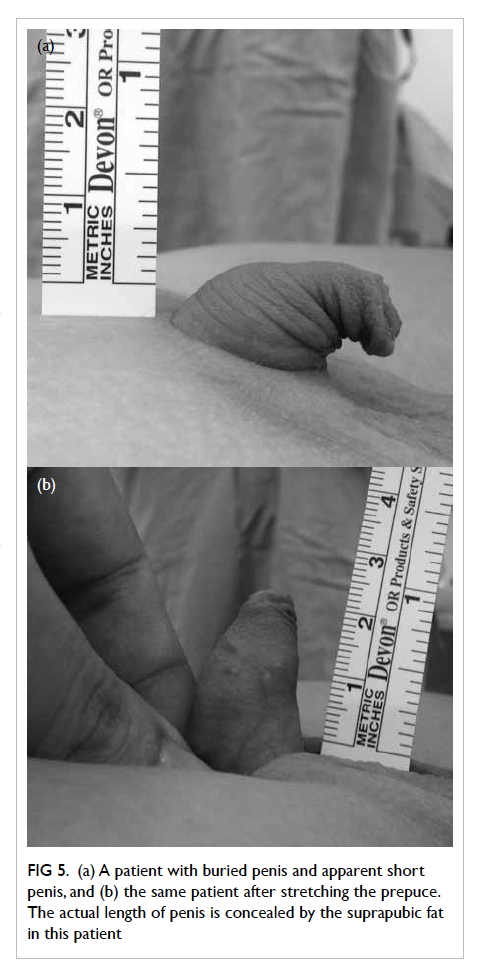

Buried penis

Buried penis is a condition where the penis is

‘trapped’ or ‘concealed’ under the suprapubic area.

There is an apparent absence or partial absence of

the penis. Figure 5 shows partial buried penis in

an 8-year-old boy. The condition was described as

‘complete’ or ‘partial’ by Crawford57 in 1977. In the

partial type, the proximal half of the penile shaft is

buried in the subcutaneous tissue. For the complete

type, the phallus is completely invisible and the glans

is covered only by prepuce. Maizels et al58 further

elaborated in 1986, offering new classifications as

‘buried penis’ (patients with redundant suprapubic

fat and/or lack of penile skin anchoring to deep fascia),

‘webbed penis’ (scrotal skin webs the penoscrotal

angle to obscure the penis), ‘trapped penis’ (the shaft

of the penis is entrapped in the scarred, prepubic

skin following trauma/overzealous circumcision),

‘micro-penis’ (a normally formed penis that is less

than two standard deviations below the mean size in

the stretched length), and ‘diminutive penis’ (a penis

that is small and/or malformed as a consequence of

epispadias/exstrophy, severe hypospadias, disorder of

sexual differentiation, or chromosomal anomalies).

O’Brien et al59 described another condition called

‘congenital megaprepuce’ in 1994 that includes

a phimotic ring and large preputial sac. Despite

these studies, buried penis is still not a well-defined

or well-classified entity. It can be congenital or

iatrogenic after overzealous circumcision. Clinicians

are reminded to examine the penis carefully and the

exact penile length should be a properly performed

‘stretched penile length’. When there is uncertainty

about the exact diagnosis, early specialist advice is

advocated.

Figure 5. (a) A patient with buried penis and apparent short penis, and (b) the same patient after stretching the prepuce. The actual length of penis is concealed by the suprapubic fat in this patient

Clinical problems

For congenital problems, anxious parents usually

seek medical advice because they feel that their

child’s penis is too short. Other problems include

local infection, urinary retention, inability to void

standing, chronic urinary dripping, and undirected

voiding. For older children, there may be pain during

erection or disturbed vaginal penetration.60 61 62

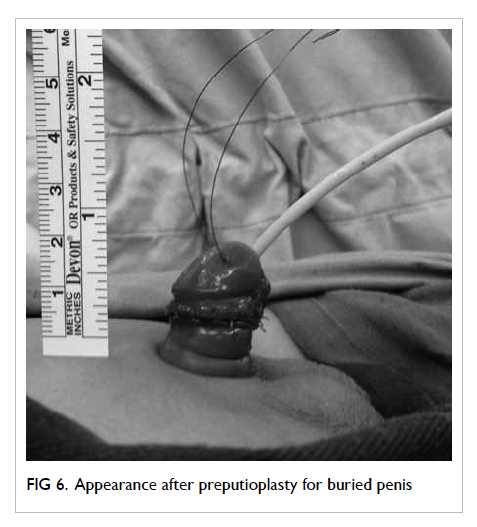

Management

Anatomically, buried penis is usually due to

insufficient outer prepuce and lack of attachment

between the penile Buck’s fascia and the pubis.63

Numerous corrective surgical techniques have been

described. The underlying principle is the degloving

of the penis, anchoring of Buck’s fascia to the pubis,

and preputioplasty (pedicled preputial flap, Z-plasty

of the prepuce, lipectomy, and skin graft) [Fig 6].64 65

A study on the comparison of quality of

life before and after surgery showed significant

improvement in sexual pleasure, urination

difficulties, and genital hygiene.66 King et al61 also reported that all patients were happy with the

aesthetic results.

Conclusions

It is essential to recognise the features of physiological

versus pathological phimosis. Physiological phimosis

(tightness of prepuce), preputial adhesion, and

smegma are common and normal in young boys,

and do not require surgical intervention. There are

potential benefits and complications of circumcision

that should be thoroughly appreciated by physicians

before discussion with parents or patient. Medical

indications for circumcision include penile

malignancy, traumatic foreskin injury, recurrent

attacks of severe balanoposthitis, and recurrent

febrile UTIs with abnormal urinary tract. Very few

international societies support routine circumcision

despite the potential medical benefits incurred.

Buried penis is a condition that may warrant surgery.

References

1. Gairdner D. The fate of the foreskin, a study of circumcision.

Br Med J 1949;2:1433-7. Crossref

2. Øster J. Further fate of the foreskin. Incidence of preputial

adhesions, phimosis, and smegma among Danish

schoolboys. Arch Dis Child 1968;43:200-3. Crossref

3. Kayaba H, Tamura H, Kitajima S, Fujiwara Y, Kato T, Kato

T. Analysis of shape and retractability of the prepuce in 603

Japanese boys. J Urol 1996;156:1813-5. Crossref

4. Rickwood AM. Medical indications for circumcision. BJU

Int 1999;83 Suppl 1:45-51. Crossref

5. Ko MC, Liu CK, Lee WK, Jeng HS, Chiang HS, Li CY. Age-specific

prevalence rates of phimosis and circumcision in

Taiwanese boys. J Formos Med Assoc 2007;106:302-7. Crossref

6. Hsieh TF, Chang CH, Chang SS. Foreskin development

before adolescence in 2149 schoolboys. Int J Urol

2006;13:968-70. Crossref

7. Stühmer A. Balanitis xerotica obliterans (post operationem)

und ihre Beziehungenzur ‘Kraurosis glandi et praeputii

penis’ [in German]. Arch Dermatol Syph (Berlin) 1928;156:613. Crossref

8. Shankar KR, Rickwood AM. The incidence of phimosis in

boys. BJU Int 1999;84:101-2. Crossref

9. Gargollo PC, Kozakewich HP, Bauer SB, et al. Balanitis

xerotica obliterans in boys. J Urol 2005;174:1409-12. Crossref

10. Babu R, Harrison SK, Hutton KA. Ballooning of the

foreskin and physiological phimosis: is there any objective

evidence of obstructed voiding? BJU Int 2004;94:384-7. Crossref

11. Herzog LW, Alvarez SR. The frequency of foreskin problems

in uncircumcised children. Am J Dis Child 1986;140:254-6. Crossref

12. Osborn LM, Metcalf TJ, Mariani EM. Hygienic care in

uncircumcised infants. Pediatrics 1981;67:365-7.

13. Camille CJ, Kuo RL, Wiener JS. Caring for the

uncircumcised penis: what parents (and you) need to

know. Contemp Pediatr 2002;11:61.

14. Simpson ET, Barraclough P. The management of the

paediatric foreskin. Aust Fam Physician 1998;27:381-3.

15. Rickwood AM, Hemalatha V, Batcup G, Spitz L. Phimosis

in boys. Br J Urol 1980;52:147-50. Crossref

16. Zampieri N, Corroppolo M, Camoglio FS, Giacomello

L, Ottolenghi A. Phimosis: stretching methods with

or without application of topical steroids? J Pediatr

2005;147:705-6. Crossref

17. Kragballe K. Topical corticosteroids: mechanisms of

action. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1989;151:7-10;

discussion 47-52.

18. Kikiros CS, Beasley SW, Woodward AA. The response

of phimosis to local steroid application. Pediatr Surg Int

1993;8:329-32. Crossref

19. Lee CH, Lee SD. Effect of topical steroid (0.05% clobetasol

propionate) treatment in children with severe phimosis.

Korean J Urol 2013;54:624-30. Crossref

20. Chu CC, Chen KC, Diau GY. Topical steroid treatment of

phimosis in boys. J Urol 1999;162:861-3. Crossref

21. Orsola A, Caffaratti J, Garat JM. Conservative treatment

of phimosis in children using a topical steroid. Urology

2000;56:307-10. Crossref

22. Ghysel C, Vander Eeckt K, Bogaert GA. Long-term

efficiency of skin stretching and a topical corticoid cream

application for unretractable foreskin and phimosis in

prepubertal boys. Urol Int 2009;82:81-8. Crossref

23. Moreno G, Corbalán J, Peñaloza B, Pantoja T. Topical

corticosteroids for treating phimosis in boys. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2014;(9):CD008973. Crossref

24. Golubovic Z, Milanovic D, Vukadinovic V, Rakic I, Perovic

S. The conservative treatment of phimosis in boys. Br J

Urol 1996;78:786-8. Crossref

25. Pileggi FO, Martinelli CE Jr, Tazima MF, Daneluzzi JC,

Vicente YA. Is suppression of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal

axis significant during clinical treatment of

phimosis? J Urol 2010;183:2327-31. Crossref

26. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Trends

in in-hospital newborn male circumcision—United States,

1999-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60:1167-8.

27. Warner L, Cox S, Kuklina E, et al. Updated trends in

the incidence of circumcision among male newborn

delivery hospitalizations in the United States, 2000-2008.

Proceedings of the National HIV Prevention Conference;

2011 Aug 26; Atlanta, Georgia, US.

28. Leung MW, Tang PM, Chao NS, Liu KK. Hong Kong

Chinese parents’ attitudes towards circumcision. Hong

Kong Med J 2012;18:496-501.

29. Shaikh N, Morone NE, Bost JE, Farrell MH. Prevalence

of urinary tract infection in childhood: a meta-analysis.

Pediatr Infect Dis J 2008;27:302-8. Crossref

30. Singh-Grewal D, Macdessi J, Craig J. Circumcision for the

prevention of urinary tract infection in boys: a systematic

review of randomised trials and observational studies.

Arch Dis Child 2005;90:853-8. Crossref

31. Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, et al. Male circumcision

for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised

trial. Lancet 2007;369:657-66. Crossref

32. Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, et al. Male circumcision

for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a

randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007;369:643-56. Crossref

33. Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J,

Sitta R, Puren A. Randomized, controlled intervention trial

of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk:

the ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS Med 2005;2:e298. Crossref

34. Lemos MP, Lama JR, Karuna ST, et al. The inner foreskin

of healthy males at risk of HIV infection harbors epithelial

CD4+ CCR5+ cells and has features of an inflamed

epidermal barrier. PLoS One 2014;9:e108954. Crossref

35. Weiss HA, Thomas SL, Munabi SK, Hayes RJ. Male

circumcision and risk of syphilis, chancroid, and genital

herpes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm

Infect 2006;82:101-9; discussion 110. Crossref

36. Diseker RA 3rd, Peterman TA, Kamb ML, et al.

Circumcision and STD in the United States: cross sectional

and cohort analyses. Sex Transm Infect 2000;76:474-9. Crossref

37. Albero G, Castellsagué X, Giuliano AR, Bosch FX. Male

circumcision and genital human papillomavirus: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Dis

2012;39:104-13. Crossref

38. Tobian AA, Serwadda D, Quinn TC, et al. Male

circumcision for the prevention of HSV-2 and HPV

infections and syphilis. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1298-309. Crossref

39. Turner AN, Morrison CS, Padian NS, et al. Male

circumcision and women’s risk of incident chlamydial,

gonococcal, and trichomonal infections. Sex Transm Dis

2008;35:689-95. Crossref

40. Van Howe RS. Sexually transmitted infections and male

circumcision: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ISRN

Urol 2013;2013:109846. Crossref

41. El Bcheraoui C, Zhang X, Cooper CS, Rose CE, Kilmarx

PH, Chen RT. Rates of adverse events associated with male

circumcision in U.S. medical settings, 2001 to 2010. JAMA

Pediatr 2014;168:625-34. Crossref

42. Weiss HA, Larke N, Halperin D, Schenker I. Complications

of circumcision in male neonates, infants and children: a

systematic review. BMC Urol 2010;10:2. Crossref

43. Bocquet N, Chappuy H, Lortat-Jacob S, Chéron G. Bleeding

complications after ritual circumcision: about six children.

Eur J Pediatr 2010;169:359-62. Crossref

44. Cathcart P, Nuttall M, van der Meulen J, Emberton M,

Kenny SE. Trends in paediatric circumcision and its

complications in England between 1997 and 2003. Br J

Surg 2006;93:885-90. Crossref

45. Wilcken A, Keil T, Dick B. Traditional male circumcision

in eastern and southern Africa: a systematic review of

prevalence and complications. Bull World Health Organ

2010;88:907-14. Crossref

46. Mihssin N, Moorthy K, Houghton PW. Retention of urine:

an unusual complication of the Plastibell device. BJU Int

1999;84:745. Crossref

47. Özdemir E. Significantly increased complication risks with

mass circumcisions. Br J Urol 1997;80:136-9. Crossref

48. Patel HI, Moriarty KP, Brisson PA, Feins NR. Genitourinary

injuries in the newborn. J Pediatr Surg 2001;36:235-9. Crossref

49. Pieretti RV, Goldenstein AM, Pieretti-Vanmarcke R. Late

complications of newborn circumcision: a common and

avoidable problem. Pediatr Surg Int 2010;26:515-8. Crossref

50. Homer L, Buchanan KJ, Nasr B, Losty PD, Corbett

HJ. Meatal stenosis in boys following circumcision for

lichen sclerosus (balanitis xerotica obliterans). J Urol

2014;192:1784-8. Crossref

51. Ceylan K, Burhan K, Yilmaz Y, Can S, Kuş A, Mustafa G.

Severe complications of circumcision: an analysis of 48

cases. J Pediatr Urol 2007;3:32-5. Crossref

52. Ince B, Gundeslioglu AO. A salvage operation for total

penis amputation due to circumcision. Arch Plast Surg

2013;40:247-50. Crossref

53. Management of foreskin conditions. British Association

of Paediatric Surgeons. Available from: http://www.baps.org.uk/resources/documents/management-foreskin-conditions/.

Accessed Jun 2015.

54. The Royal Australasian College of Physicians. Circumcision

of infant males. 2010. Available from: https://www.racp.edu.au/docs/default-source/advocacy-library/circumcision-of-infant-males.pdf. Accessed Jun 2015.

55. American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on

Circumcision. Circumcision policy statement. Pediatrics

2012;130:585-6. Crossref

56. American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on

Circumcision. Male circumcision. Pediatrics

2012;130:e756-85. Crossref

57. Crawford BS. Buried penis. Br J Plast Surg 1977;30:96-9. Crossref

58. Maizels M, Zaontz M, Donovan J, Bushnick PN, Firlit

CF. Surgical correction of the buried penis: description

of a classification system and a technique to correct the

disorder. J Urol 1986;136:268-71.

59. O’Brien A, Shapiro AM, Frank JD. Phimosis or congenital

megaprepuce? Br J Urol 1994;73:719-20. Crossref

60. Mattsson B, Vollmer C, Schwab C, et al. Complications of

a buried penis in an extremely obese patient. Andrologia

2012;44 Suppl 1:826-8. Crossref

61. King IC, Tahir A, Ramanathan C, Siddiqui H. Buried

penis: evaluation of outcomes in children and adults,

modification of a unified treatment algorithm, and review

of the literature. ISRN Urol 2013;2013:109349. Crossref

62. Donatucci CF, Ritter EF. Management of the buried penis

in adults. J Urol 1998;159:420-4. Crossref

63. Chin TW, Tsai HL, Liu CS. Modified prepuce unfurling for

buried penis: a report of 12 years of experience. Asian J

Surg 2015;38:74-8. Crossref

64. Liu X, He DW, Hua Y, Zhang DY, Wei GH. Congenital

completely buried penis in boys: anatomical basis and

surgical technique. BJU Int 2013;112:271-5. Crossref

65. Chu CC, Chen YH, Diau GY, Loh IW, Chen KC. Preputial

flaps to correct buried penis. Pediatr Surg Int 2007;23:1119-21. Crossref

66. Hughes DB, Perez E, Garcia RM, Aragón OR, Erdmann

D. Sexual and overall quality of life improvements after

surgical correction of “buried penis”. Ann Plast Surg

2016;76:532-5. Crossref