Hong Kong Med J 2016 Feb;22(1):6–10 | Epub 9 Oct 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154568

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Excess mortality for operated geriatric hip fracture in Hong Kong

LP Man, MB, BS, MRCSEd;

Angela WH Ho, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery);

SH Wong, MB, BS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)

Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Caritas Medical Centre, Shamshuipo, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr LP Man (mlp257@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Geriatric hip fracture places an

increasing burden to health care systems around the

world. We studied the latest epidemiology trend of

geriatric hip fracture in Hong Kong, as well as the

excess mortality for patients who had undergone

surgery for hip fracture.

Methods: This descriptive epidemiology study was

conducted in the public hospitals in Hong Kong. All

patients who underwent surgery for geriatric hip

fracture in public hospitals from January 2000 to

December 2011 were studied. They were retrieved

from the Clinical Management System of the

Hospital Authority of Hong Kong. Relevant data

were collected using the Clinical Data Analysis and

Reporting System of the Hospital Authority. The

actual and projected population size, and the age- and

sex-specific mortality rates were obtained from

the Census and Statistics Department of Hong Kong.

The 30-day, 1-year and 5-year mortality, and excess

mortality following surgery for geriatric hip fracture

were calculated.

Results: There was a steady increase in the incidence

of geriatric hip fracture in Hong Kong. The annual

risk of geriatric hip fracture was decreasing in both

sexes. Female patients aged 65 to 69 years had the

lowest 1-year and 5-year mortality of 6.91% and

23.80%, respectively. Advancing age and male sex

were associated with an increase in mortality and a

higher excess mortality rate following surgery.

Conclusion: The incidence of geriatric hip fracture

is expected to increase in the future. The exact

reason for a higher excess mortality rate in male

patients remains unclear and should be the direction

for future studies.

New knowledge added by this study

- Advancing age and male sex were associated with an increase in mortality and a higher excess mortality rate in Hong Kong following surgery for hip fracture.

- The burden of geriatric hip fracture is expected to increase.

- Future studies should investigate the cause of an increased excess mortality in male patients who sustain a geriatric hip fracture.

Introduction

Geriatric hip fracture places an increasing burden

on health care service providers around the world.

Previous studies have shown that it is associated

with significant morbidity and mortality.1 2 3 With

the ageing population in many parts of Asia, it has

been estimated that over half of all hip fractures

will occur in Asia in 2050.4 Studies in France5 and the US6 have reported a drop in the incidence rate

of geriatric hip fracture in the elderly population.

This trend, however, has not been echoed by similar

studies in Korea7 and Japan.8 Epidemiological studies performed in Hong Kong in 2007 and 2012 showed

that, similar to western countries, there was a drop in

the incidence rate of hip fracture in the territory.9 10

Hong Kong has one of the longest life

expectancies in the world.11 The total number of

geriatric hip fractures is expected to increase. It

will therefore be important for policy-makers and

society as a whole to adequately forecast future

trends in the disease to prepare for the challenges

ahead. This study aimed to analyse the latest trend

in the epidemiology of geriatric hip fracture in Hong

Kong, as well as to investigate the mortality rate and

excess mortality rate in patients who underwent

surgery for geriatric hip fracture.

Methods

Approximately 98% of geriatric hip fractures are

managed in public hospitals run by the Hospital

Authority of Hong Kong.10 All patients admitted to

a public hospital in Hong Kong are assigned a code

in the Clinical Management System by the attending

doctor(s). The system also includes information

on age, sex, principal diagnosis, and period of

hospitalisation. Relevant data, including date of

death, were collected using the Clinical Data Analysis

and Reporting System (CDARS) from the Hospital

Authority. All cases between January 2000 and

December 2011 with a disease coding of acute hip

fracture (ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes 820.8, 820.09,

820.02, 820.03, 820.20, and 820.22) were retrieved.

Operations for geriatric hip fracture were defined as

a patient-episode with ICD-9-CM procedure code of

81.52, 51.51, 81.40, 79.15, 79.35, or 78.55.

Only patients with a disease code for acute

hip fracture and procedure code for geriatric hip

fracture were included in the current study. Patients

who were non-Chinese, who had an old fracture,

were managed non-operatively, had a second hip

fracture or complications of primary hip fracture

were excluded. Based on the date of death, we

analysed the 30-day and 1-year mortality regardless

of cause of death. Postoperative 5-year mortality rate

was calculated based on data from patients who underwent surgery from year 2000 to 2006.

Excess mortality is defined by the World

Health Organization as “Mortality above what

would be expected based on the non-crisis mortality

rate in the population of interest.”12 In this study, the

excess mortality rate was calculated by subtracting

the age- and sex-specific mortality from the age- and

sex-specified 1-year mortality of operated geriatric

hip fracture. The age- and sex-specific mortality rates

for the year 2006 were used for analysis. The actual

and projected population size, and the age- and

sex-specific mortality rates13 were obtained from the

Census and Statistics Department of the HKSAR

Government.

Results

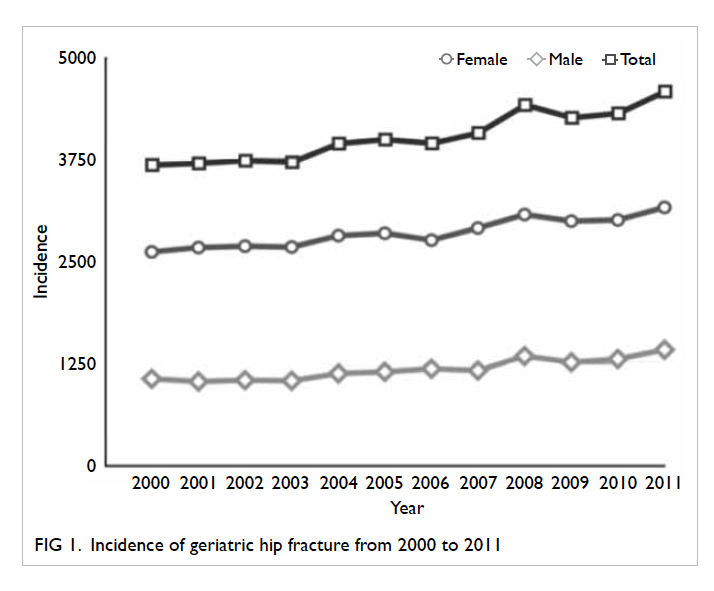

From January 2000 to December 2011, the annual

number of patients admitted to public hospitals and

who underwent surgery for hip fracture increased

from 3678 to 4579. The annual incidence of geriatric

hip fracture during the study period is shown in

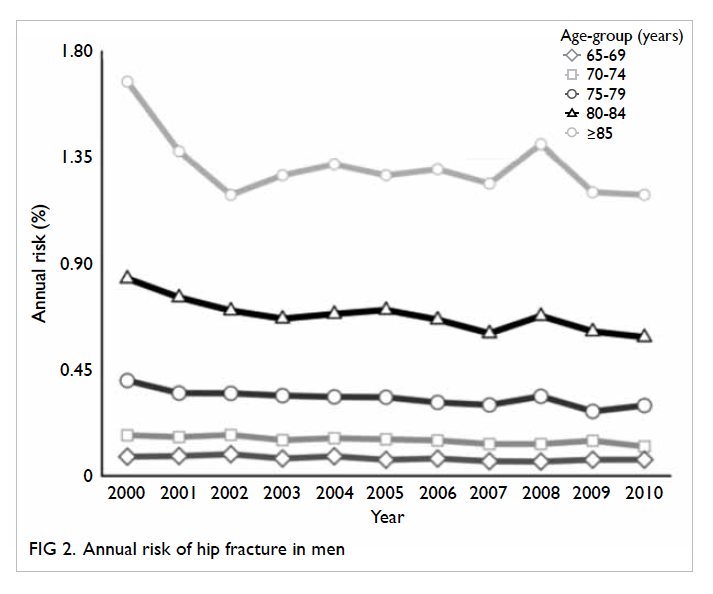

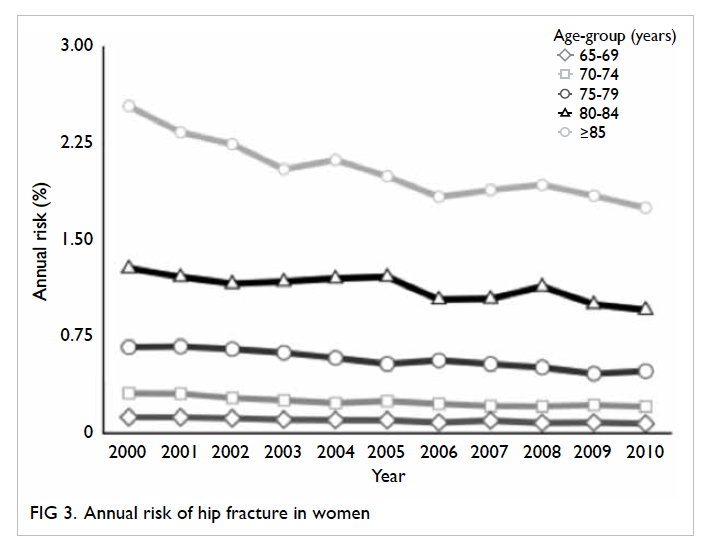

Figure 1. A slightly decreasing annual risk of hip

fracture was observed for both male and female

patients (Figs 2 and 3).

A total of 48 992 cases were retrieved after

excluding non-Chinese patients, old fractures,

cases managed non-operatively, second hip

fractures, repeated admission for the same fracture, and

complications of primary hip fracture.

Patient age ranged from 65 to 112 years with

a mean and median age of 82.1 and 82.0 years,

respectively. The overall 30-day and 1-year mortality

was 3.01% and 18.56%, respectively.

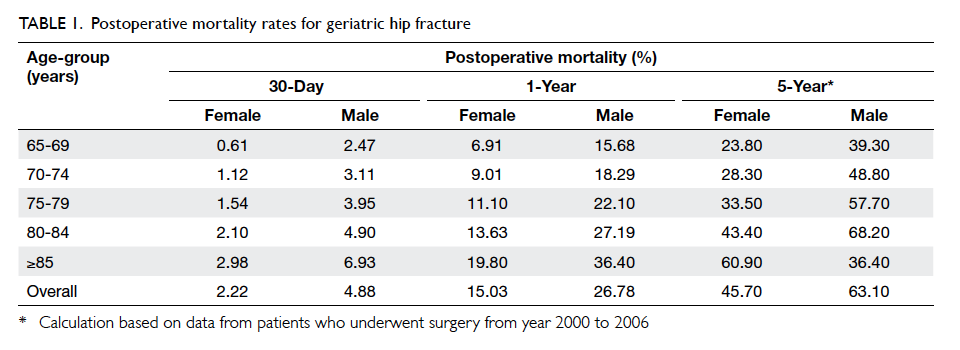

The age- and sex-specific mortality after 30

days, 1 year, and 5 years for operated hip fracture are

shown in Table 1. Female patients aged 65 to 69 years

had the lowest 1-year and 5-year mortality of 6.91%

and 23.80%, respectively. An increase in mortality

was observed with advancing age and male sex.

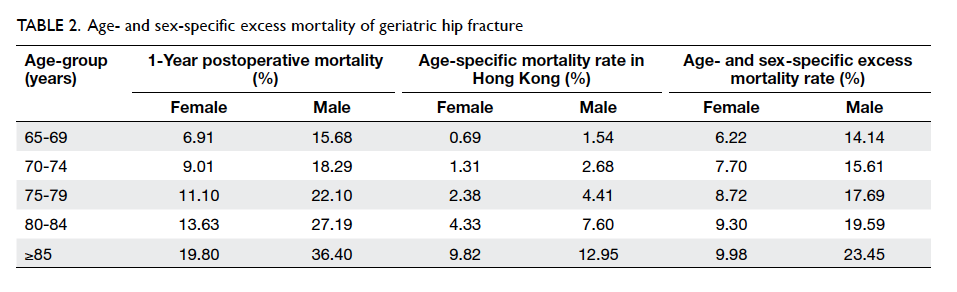

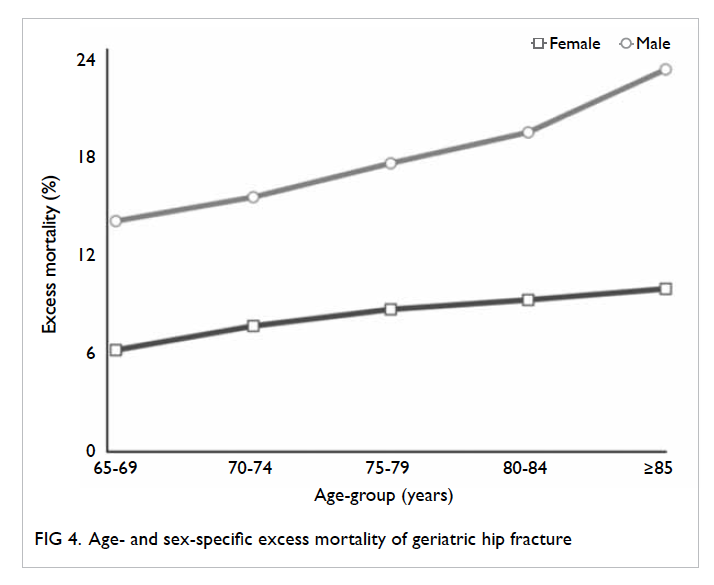

The excess mortality rate in different age and

sex groups is shown in Table 2 and Figure 4. Male

gender and increasing age were associated with

a higher excess mortality rate after operation for

geriatric hip fracture. The excess mortality for a male

patient aged ≥85 years was 23.45%.

Discussion

A slight decrease in the annual risk of geriatric hip

fracture was noted in this study. This trend echoes that

of similar studies in the territory and in some western

countries.5 6 10 Such a decrease has been postulated

to be related to improved availability of medical

intervention to prevent osteoporosis, increased

attention to menopause and hormonal replacement

therapy, changes in lifestyle, and community fall prevention

programmes. Nonetheless few studies

have been able to prove any causal relationship.

Surgery is generally offered to patients with

geriatric hip fracture in order to decrease the

morbidity and mortality associated with prolonged

immobilisation. In this study, patients who were

managed non-operatively were excluded as they

represented a very small proportion of patients

(estimated to be <1%) with poor pre-morbid medical

conditions and very high anaesthetic risk.

Despite the decreasing annual risk of geriatric

hip fracture, it is important to relate this to the ageing

population in the territory. Using the projected

percentage of elderly aged ≥65 years in Hong Kong,11

and assuming that the annual risk of hip fracture

remains the same, we estimate that there will be

more than 6300 cases of hip fracture in the year 2020.

In the year 2040, the annual incidence of geriatric

hip fracture will be more than 14 500, more than a

3-fold increase from 2011. Unless effective primary

prevention measures are put in place, the burden of

geriatric hip fracture on the public health system will

continue to increase. Policy-makers should invest in

the relevant specialties and departments in order to

tackle the inevitable challenges ahead.

To our knowledge this is the first study to

review the excess mortality of operated geriatric hip

fracture in the territory. A systematic epidemiological

review by Abrahamsen et al14 showed that the 1-year

excess mortality rate following hip fracture ranged

from 8.4% to 36%. In this study, the 1-year excess

mortality following surgery for geriatric hip fracture

ranged from 6.22% to 23.45%. Echoing the result of

Abrahamsen et al,14 we also identified that men had

a higher excess mortality rate after operation for

geriatric hip fracture. The reasons for this higher

excess mortality rate in males remain unclear. Endo

et al15 reported that male gender was a risk factor

for sustaining postoperative complications such as

pneumonia, arrhythmia, delirium, and pulmonary

embolism, even after controlling for age and the

American Society of Anesthesiologists rating, as

well as a higher mortality 1 year after hip fracture.

Another study by Wehren et al16 reported an

increased rate of death from infection in males for

at least 2 years after hip fracture, suggesting that

infection may contribute to the differential risk of

death.

There are limitations to the present study.

Patients with geriatric hip fracture who were treated

in the private sector were not included, although

they constituted only a small proportion of the

total number of cases. Chau et al10 reported that

approximately 98% of hip fractures were managed in

the Hospital Authority.

In the CDARS of the Hospital Authority, the

date of death was provided by the death registry of

the Immigration Department of Hong Kong. We

were unable to capture data for deaths that occurred

outside the territory. Under the laws of Hong Kong,

only deaths that occur in Hong Kong are registered

with the Deaths Registries. According to the Census

and Statistics Department, approximately 9% of

the elderly population resides in the mainland.17 As

Hong Kong residents are currently not eligible for

free or subsidised health services in the mainland,

we believe many elderly people will return to Hong

Kong for medical treatment.

Other risk factors that may contribute to the

excess mortality such as smoking and pre-morbid

health status were not included in the present

study. Further studies should also investigate the

incidence and mortality of other fragility fractures.

The effect of primary and secondary prevention

by anti-osteoporotic medications on the incidence

of geriatric hip fracture is also a potential area for

further study.

Conclusion

Geriatric hip fracture will continue to be a

major challenge for the health care system in the

foreseeable future. Despite the emphasis on early

surgery for geriatric hip fractures in recent years, the

risk of premature death remained high for patients

who underwent surgery for hip fracture. Future

studies should be directed to identify the causes of

this excess mortality and patients who are

at increased risk of premature death, so that early

interventions can be initiated to reduce their risk.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr Tony Kwok and

the CDARS team of Hospital Authority for their help

in data retrieval.

References

1. Mullen JO, Mullen NL. Hip fracture mortality. A

prospective, multifactorial study to predict and minimize

death risk. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1992;(280):214-22.

2. Omsland TK, Emaus N, Tell GS, et al. Mortality following

the first hip fracture in Norwegian women and men (1999-2008). A NOREPOS study. Bone 2014;63:81-6. Crossref

3. Randell AG, Nguyen TV, Bhalerao N, Silverman SL,

Sambrook PN, Eisman JA. Deterioration in quality of life

following hip fracture: a prospective study. Osteoporos Int

2000;11:460-6. Crossref

4. Cooper C, Campion G, Melton LJ 3rd. Hip fractures

in the elderly: a world-wide projection. Osteoporos Int

1992;2:285-9. Crossref

5. Maravic M, Taupin P, Landais P, Roux C. Change in

hip fracture incidence over the last 6 years in France.

Osteoporos Int 2011;22:797-801. Crossref

6. Brauer CA, Coca-Perraillon M, Cutler DM, Rosen AB.

Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United

States. JAMA 2009;302:1573-9. Crossref

7. Yoon HK, Park C, Jang S, Jang S, Lee YK, Ha YC. Incidence

and mortality following hip fracture in Korea. J Korean

Med Sci 2011;26:1087-92. Crossref

8. Hagino H, Yamamoto K, Ohshiro H, Nakamura T,

Kishimoto H, Nose T. Changing incidence of hip, distal

radius, and proximal humerus fractures in Tottori

Prefecture, Japan. Bone 1999;24:265-70. Crossref

9. Kung AW, Yates S, Wong V. Changing epidemiology

of osteoporotic hip fracture rates in Hong Kong. Arch

Osteoporos 2007;2:53-8. Crossref

10. Chau PH, Wong M, Lee A, Ling M, Woo J. Trends in hip

fracture incidence and mortality in Chinese population

from Hong Kong 2001-09. Age Ageing 2013;42:229-33. Crossref

11. Hong Kong Population Projections 2012-2041, Census

and Statistics Department. Available from: http://www.censtatd.gov.hk/. Accessed Jun 2015.

12. Definitions: emergencies. Available from: http://www.who.int/hac/about/definitions/en/. Accessed Jun 2015.

13. The mortality trend in Hong Kong, 1981 to 2013. Hong Kong

Monthly Digest of Statistics. November 2014, HKSAR: Census and Statistics Department. Available from: http://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B71411FB2014XXXXB0100.pdf. Accessed Jun 2015.

14. Abrahamsen B, va Staa T, Ariely R, Olson M, Cooper

C. Excess mortality following hip fracture: a systematic

epidemiological review. Osteoporos Int 2009;20:1633-50. Crossref

15. Endo Y, Aharonoff GB, Zuckerman JD, Egol KA, Koval KJ.

Gender differences in patients with hip fracture: a greater

risk of morbidity and mortality in men. J Orthop Trauma

2005;19:29-35. Crossref

16. Wehren LE, Hawkes WG, Orwig DL, Hebel JR,

Zimmerman SI, Magaziner J. Gender differences in

mortality after hip fracture: the role of infection. J Bone

Miner Res 2003;18:2231-7. Crossref

17. Characteristics of Hong Kong older persons residing in

the Mainland of China. Hong Kong Monthly Digest of

Statistics. September 2011. HKSAR: Census and Statistics

Department. Available from: http://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B71109FC2011XXXXB0100.pdf. Accessed Jul 2015.