Hong Kong Med J 2015 Dec;21(6):518–23 | Epub 11 Sep 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144456

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Childhood intussusception: 17-year experience at a tertiary referral centre in Hong Kong

Carol WY Wong, MB, BS, MRCSEd1;

Ivy HY Chan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery)1;

Patrick HY Chung, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery)1;

Lawrence CL Lan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery)1;

Wendy WM Lam, MB, BS, FHKAM (Radiology)2;

Kenneth KY Wong, PhD, FHKAM (Surgery)1;

Paul KH Tam, ChM, FHKAM (Surgery)1

1 Department of Surgery, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

2 Department of Radiology, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof Kenneth KY Wong (kkywong@hku.hk)

Abstract

Objectives: To review all paediatric patients with

intussusception over the last 17 years.

Design: Retrospective case series.

Setting: A tertiary centre in Hong Kong.

Patients: Children who presented with

intussusception from January 1997 to December

2014 were reviewed.

Main outcome measures: The duration of

symptoms, successful treatment modalities,

complication rate, and length of hospital stay were

studied.

Results: A total of 173 children (108 male, 65 female)

presented to our hospital with intussusception

during the study period. Their median age at

presentation was 12.5 months (range, 2 months to

16 years) and the mean duration of symptoms was

2.3 (standard deviation, 1.8) days. Vomiting was

the most common symptom (76.3%) followed by

abdominal pain (46.2%), per rectal bleeding or red

currant jelly stool (40.5%), and a palpable abdominal

mass (39.3%). Overall, 160 patients proceeded to

pneumatic or hydrostatic reduction, among whom

127 (79.4%) were successful. Three (1.9%) patients

had bowel perforation during the procedure. Early

recurrence of intussusception occurred in four

(3.1%) patients with non-operative reduction. No

recurrence was reported in the operative group. The

presence of a palpable abdominal mass was a risk

factor for operative treatment (relative risk=2.0; 95%

confidence interval, 1.8-2.2). Analysis of our results

suggested that duration of symptoms did not affect

the success rate of non-operative reduction.

Conclusions: Non-operative reduction has a high

success rate and low complication rate, but the

presence of a palpable abdominal mass is a risk

factor for failure. Operative intervention should not

be delayed in those patients who encounter difficult

or doubtful non-operative reduction.

New knowledge added by this

study

- Non-operative reduction of intussusception has a high success rate and low complication rate, even in delayed presentation of over 72 hours.

- The presence of a palpable abdominal mass is a risk factor for failure of non-operative reduction.

- Non-operative reduction is recommended as the first-line treatment for children with intussusception.

- Operative intervention should not be delayed in those patients who encounter difficult or doubtful non-operative reduction.

Introduction

Intussusception is the most common cause of

intestinal obstruction in infants and young children

between the age of 3 months and 3 years, and the

peak age of presentation is 4 to 8 months.1 The

invagination of proximal bowel into more distal

bowel results in venous congestion and bowel wall

oedema. If this condition is not promptly diagnosed

and treated, arterial obstruction and bowel necrosis

and perforation may occur.2 Approximately 90% of

intussusceptions in the paediatric age-group are

ileocolic and idiopathic,3 presumably caused by

lymphoid hyperplasia that has been suggested as the

‘lead point’ in its pathogenesis.4 Viral infection may

also play a role.5 6 7 8

The reported incidence of a pathological

lead point in paediatric intussusception is

approximately 6%,9 the most common of which

is Meckel’s diverticulum.10 Systemic conditions

such as Henoch-Schönlein purpura, Peutz-Jeghers

syndrome, and familial polyposis can also increase

the risk of intussusception. Abdominal trauma and

postoperative abdomen have also been reported to

pose a higher risk for intussusception.11 12 13 14

The presenting symptoms of intussusception

are often non-specific and may mimic viral gastro-enteritis,

presenting as vomiting and diarrhoea. The

classic triad of red currant jelly stool, abdominal

pain, and abdominal mass is not often encountered,

and the diagnosis may easily be delayed or missed.15

Plain abdominal films are neither sensitive nor

specific for intussusception and may be completely

normal.16 The most consistent finding is a paucity of

gas in the right iliac fossa. Other possible features

include soft tissue mass, target sign, or meniscus

sign.17 The first-line investigation for diagnosis of

intussusception in children is abdominal ultrasound,

given its high sensitivity (98%-100%) and specificity

(88%-100%).18

Non-operative reduction methods for

intussusception include barium enema, and

hydrostatic or pneumatic reduction.19 Pneumatic

reduction is currently the preferred standard

treatment, given the greater ease of performing

the examination, the lesser morbidity with

complications, and the slightly higher success rate of

84% to 100%.20 21 22

Operative reduction is required when non-operative

reduction is either contra-indicated

(eg peritonitis, perforation, profound shock) or

unsuccessful. Open surgery has been the conventional

approach although laparoscopic reduction is also

feasible and successful in uncomplicated cases.23 24

In this study, we aimed to review our hospital’s

experience in the management of paediatric

intussusception over the last 17 years, with a focus

on assessing the efficacy of non-operative reduction

and identifying the risk factors that may lower its

success rate.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of children who

presented with intussusception from January 1997 to

December 2014 in our hospital. We started with the

year 1997 as some of earlier records were incomplete.

Patient demographics, clinical presentation,

duration of symptoms, treatment modalities,

complication rate, and length of hospital stay were

studied. The method of non-operative reduction in

our institution was ultrasound-guided hydrostatic

reduction before 2005 and pneumatic reduction

with fluoroscopy after 2005, as the latter was easier

and faster to perform. The procedure was performed

by paediatric radiologists, with a paediatric surgeon

available if necessary. In pneumatic reduction, air

is insufflated via a Foley catheter (with size of 18-Fr

to 22-Fr, depending on patient’s size, with balloon

inflated with 10 mL water) placed inside the patient’s

rectum under pressure monitoring at 120 mm Hg.

Our radiologists would perform a maximum of three

attempts. The patient might be given intravenous

midazolam at a dose of 0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg if necessary.

Successful reduction was demonstrated by free flow of

air into the terminal ileum and disappearance of the

caecal soft tissue mass.

For laparoscopic reduction, a 5-mm subumbilical

port was used for camera access. Another

two working ports (one in the upper and one in

the lower abdomen) were inserted. Reduction of

intussusception was performed with laparoscopic

graspers. In open reduction, manual reduction was

achieved by milking the intussusceptum out of the

intussuscipient. Bowel resection was performed

when bowel necrosis was found intra-operatively.

Data analysis was carried out using the

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Windows

version 21.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US). Mean values

were expressed with standard deviation. Continuous

variables were compared with Mann-Whitney U

test and categorical values with Chi squared test.

Results were considered statistically significant

when P≤0.05. Comparison of success, recurrence,

and complication rates between hydrostatic and

pneumatic reduction groups was performed. The

length of hospital stay was also compared.

Results

A total of 173 children (108 male, 65 female)

presented to our hospital with intussusception

during the study period. Of them, 83 (48%) were

admitted directly to our paediatric surgical ward, 50

(29%) were referred from the paediatric medical ward

in our hospital, and the remaining 40 (23%) were

referred from other public and private hospitals. The

median age at presentation was 12.5 months (range,

2 months to 16 years) and the mean (± standard

deviation) duration of presenting symptoms was 2.3

± 1.8 days. The common presenting symptoms and

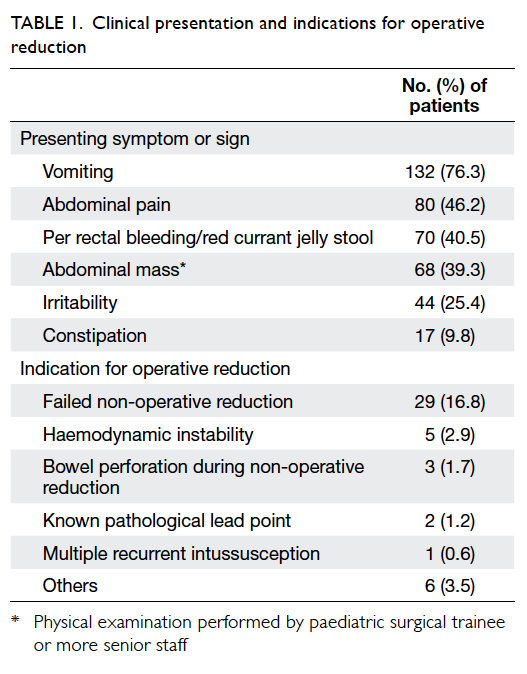

their percentage of occurrence are shown in Table 1. The most common symptom reported was vomiting

and occurred in 132 (76.3%) patients.

All patients except one were diagnosed by

ultrasonography. One patient underwent computed

tomographic scan for diagnosis due to an atypical

presentation of intussusception. All patients

underwent either non-operative or operative

treatment within 24 hours of admission. Pneumatic

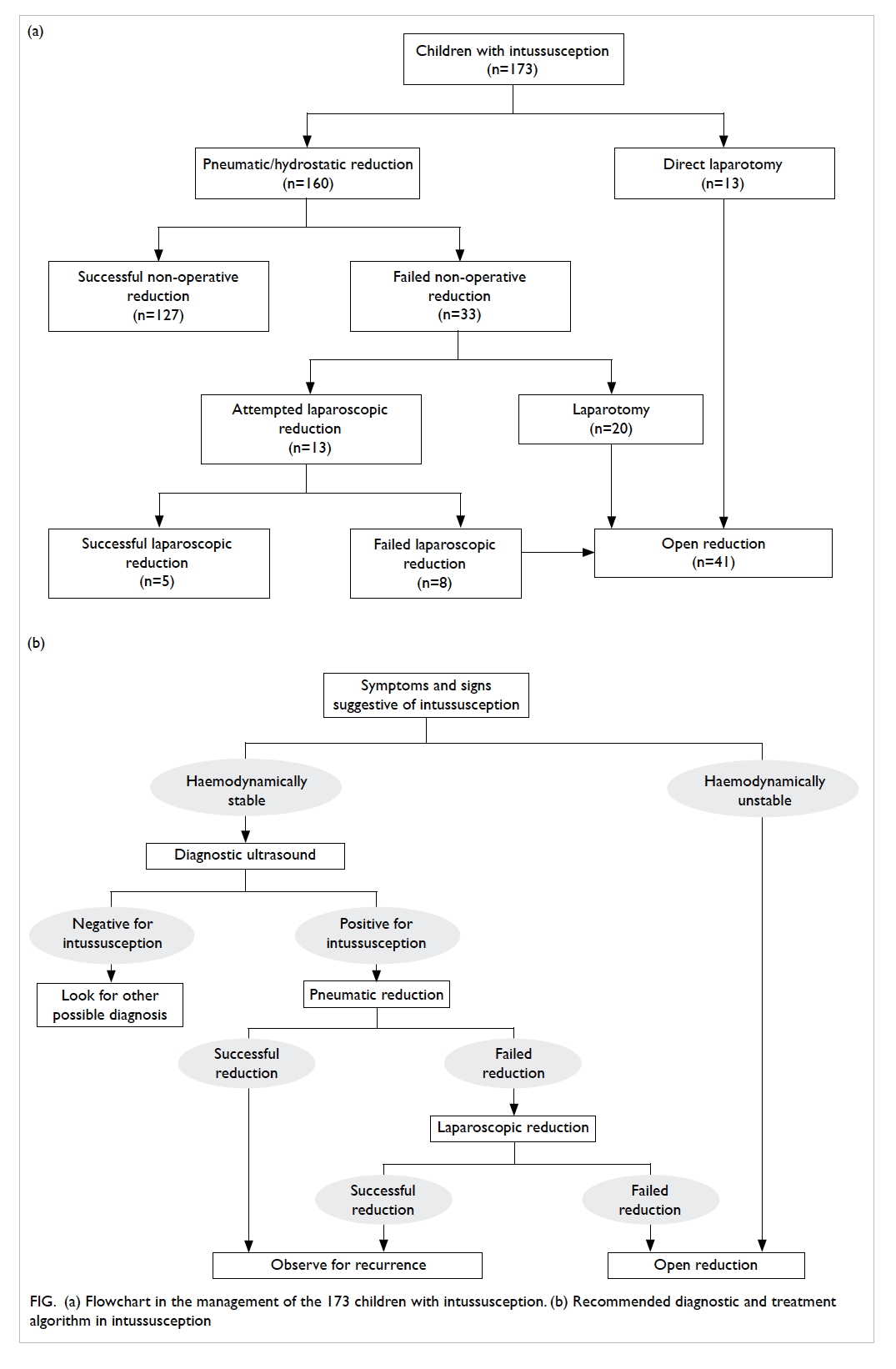

or hydrostatic reduction (Fig a) was performed in 160 patients, among which 127 (79.4%) were

successful and three (1.9%) were complicated by

bowel perforation. A total of 46 patients in our

study required operative reduction, but two of the

intussusceptions were found to be reduced upon

laparotomy. These radiological misdiagnoses could

be due to mistaken identity of the oedematous

ileocaecal valve for intussusceptum. The indications

for operative treatment are summarised in Table 1. Early recurrence of intussusception (<72 hours

post-reduction) occurred in four (3.1%) of the 127

patients who had initial successful non-operative

reduction. No recurrence was reported in patients

treated surgically. Laparoscopic reduction was

attempted in 13 patients, among whom five (38.5%)

were successful. Conversion to open reduction was

required in five patients because of the need for

bowel resection and in a further three due to difficult

reduction. Among the 46 patients who required

operative reduction, 23 (50%) required bowel

resection. A pathological lead point was noted intra-operatively

in seven (15.2%) patients and four had a

perforated bowel (three of which were complications

of non-operative reduction). The remaining 12 had

non-viable gangrenous bowel that was subsequently

confirmed by histology. The operations were

complicated with one burst abdomen and one

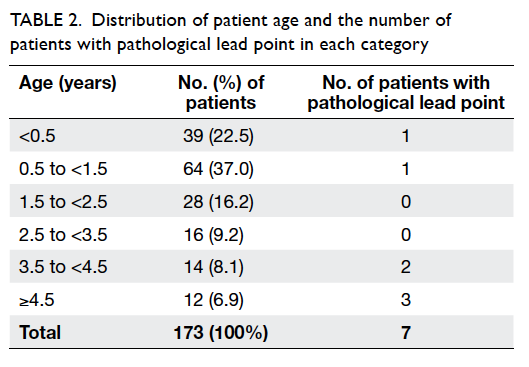

anastomotic leak. The age distribution in our

cohort of patients and the number of patients with

pathological lead point are shown in Table 2.

Figure. (a) Flowchart in the management of the 173 children with intussusception. (b) Recommended diagnostic and treatment algorithm in intussusception

Table 2. Distribution of patient age and the number of patients with pathological lead point in each category

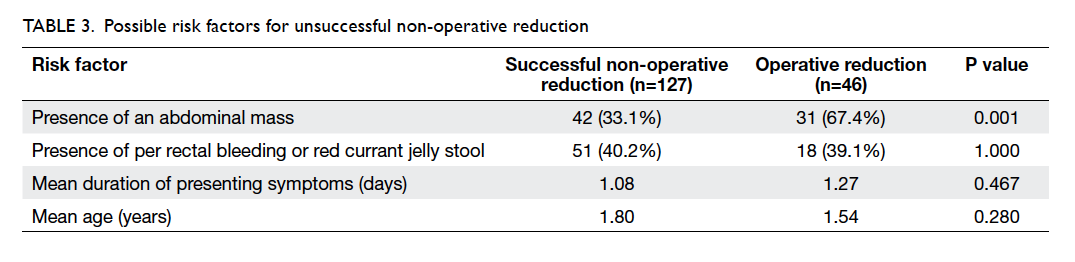

We next analysed the possible risk factors for

unsuccessful non-operative reduction in the 160

patients (Table 3). The only statistically significant

factor was the presence of an abdominal mass

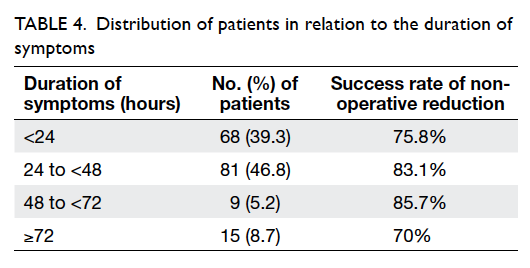

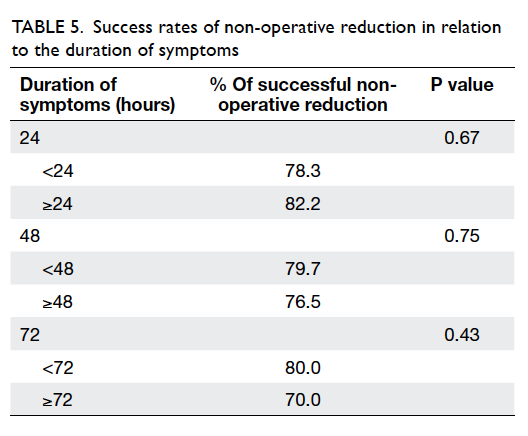

(relative risk=2.0; 95% confidence interval, 1.8-2.2). The distribution of the duration of symptoms

is presented in Table 4. Nonetheless, the duration

of symptoms and the extent of the intussusception

did not appear to affect the chance of a successful

non-operative reduction (Table 5). There were 129

patients with intussusception at the hepatic flexure

or a more proximal site, 93 (72.1%) of whom had

successful non-operative reduction; 44 presented

with intussusception at the transverse colon or a

more distal site, of whom 34 (77.3%) underwent

successful non-operative reduction. There was

no significant difference in the success rate of

non-operative reduction between the two groups

(P=0.56). Approximately 50% of patients were

admitted directly to our ward from the beginning.

There was no difference in the success rate of non-operative

reduction between this group of patients

and those who were referred from other wards or

hospitals (77.1% vs 77.3%, P=1.00).

The overall success rate of non-operative

reduction was 79.4%. We also compared the success

rate for the two non-operative treatment modalities.

There was no statistically significant difference

between the success rate of hydrostatic reduction

(81.5%) versus pneumatic reduction (77.2%) in our

study (P=0.56).

There was a statistically significant difference

in the median length of post-reduction hospital stay

for patients who were successfully treated non-operatively

(3 days; range, 1-12 days) versus operatively

(7.5 days; range, 3-73 days; P=0.01).

Discussion

Intussusception is a true paediatric surgical

emergency and is second only to appendicitis as

the most common cause of an acute abdominal

emergency in children.25 The complete classic triad of

intermittent abdominal pain, red currant jelly stool,

and a palpable abdominal mass is not a common

presentation.26 Only five (2.9%) of our patients were

documented to have all three symptoms present at

the time of hospital admission. In accordance with

previous studies, vomiting was the most common

presenting symptom.4 27 Per rectal bleeding or red

currant jelly stool signify bowel ischaemia and

mucosal sloughing but is a rather late sign and was

present in only 40.5% of our patients. Nonetheless, all

except one patient had at least one of the symptoms

of abdominal pain, abdominal mass, red currant

jelly stool, vomiting, or irritability. These symptoms

should be actively sought in any patient in whom

intussusception is suspected.

The most reliable abdominal sign, if present, is

a palpable mass in the right upper quadrant of the

abdomen. It was present in 39.3% of our patients,

and was a risk factor for the need of operative

treatment. We postulate that a palpable mass may

signify relatively longer duration of intussusception

that causes complete intestinal obstruction, thus

rendering non-operative reduction less successful as

it becomes more difficult for the reduction medium

to pass through. Many children with intussusception

present with non-specific signs and symptoms, thus

the diagnosis may easily be delayed or missed.15

Therefore, as clinicians we must maintain a high

index of suspicion in order to identify this emergency

in a timely manner. Early referral of suspected cases

to a tertiary treatment centre can significantly reduce

morbidity in the child.

With positive sonographic findings of

intussusception, an enema is reserved for therapeutic

purposes, although it may be necessary for diagnosis

when ultrasonography findings are questionable.

Computed tomography is seldom needed for

diagnosis of paediatric intussusception, except in

cases where an associated underlying pathological

lead point is suspected. Our recommended diagnostic

and treatment algorithm is summarised in Figure b. Pneumatic reduction is currently our preferred

standard treatment of intussusception, given the

greater ease of performing the examination, lesser

morbidity with complication, and the high success

rate.20 21 22 Major advantages of air enema reduction

include a relatively low radiation dose and improved

safety with constant pressure monitoring.28 29 The

perforation rate is reported to be less than 3%.30

In a randomised trial performed by Hadidi and El

Shal,22 pneumatic reduction was concluded to be

the modality with fewest complications and highest

success rate, when compared with barium enema

and hydrostatic reduction. In our study, there was

no statistically significant difference in the success

rate between hydrostatic reduction and pneumatic

reduction (81.5% vs 77.2%, P=0.56). We believe that

this is attributable to the fact that both hydrostatic

and pneumatic reductions are based on similar

principles.

Laparoscopic reduction has been demonstrated

to be feasible and successful in uncomplicated

intussusception.23 24 In our series, five (62.5%) of

the eight conversions from laparoscopic to open

reduction were due to the need for bowel resection.

Non-operative reduction has a high overall

success rate and low complication and recurrence

rates. A high success rate was observed even in the

group of patients with delayed presentation of over

72 hours. It also leads to a shorter hospital stay and

is therefore recommended as the first-line treatment

of this condition.

The presence of a palpable abdominal mass is

a risk factor for failure of non-operative reduction.

Operative intervention should not be delayed in

these patients who encounter difficult or doubtful

non-operative reduction. For patients in whom non-operative

reduction fails, laparoscopic reduction

appears to be a feasible option. From our experience,

a significant proportion of this group of patients

require bowel resection. If the viability of the bowel

is doubtful during laparoscopy, early conversion to

open surgery should be performed in order to avoid

delay in treatment.

Conclusions

Non-operative reduction has a high success rate and

low complication rate, but the presence of a palpable

abdominal mass is a risk factor for failure. Operative

intervention should not be delayed in these patients

who encounter difficult or doubtful non-operative

reduction.

References

1. Bines J, Ivanoff B. Acute intussusception in infants and

children: incidence, clinical presentation and management: a global perspective. Report 02.19. Geneva: World Health

Organization; 2002.

2. Stringer MD, Pablot SM, Brereton RJ. Paediatric

intussusception. Br J Surg 1992;79:867-76. Crossref

3. Bajaj L, Roback MG. Postreduction management of

intussusception in a children’s hospital emergency

department. Pediatrics 2003;112:1302-7. Crossref

4. DiFiore JW. Intussusception. Semin Pediatr Surg

1999;8:214-20. Crossref

5. Mayell MJ. Intussusception in infancy and childhood in

Southern Africa. A review of 223 cases. Arch Dis Child

1972;47:20-5. Crossref

6. Mangete ED, Allison AB. Intussusception in infancy

and childhood: an analysis of 69 cases. West Afr J Med

1994;13:87-90.

7. Asano Y, Yoshikawa T, Suga S, Hata T, Yamazaki T, Yazaki

T. Simultaneous occurrence of human herpesvirus 6

infection and intussusception in three infants. Pediatr

Infect Dis J 1991;10:335-7. Crossref

8. O’Ryan M, Lucero Y, Peña A, Valenzuela MT. Two year review

of intestinal intussusception in six large public hospitals of

Santiago, Chile. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2003;22:717-21. Crossref

9. Blakelock RT, Beasley SW. The clinical implications of non-idiopathic

intussusception. Pediatr Surg Int 1998;14:163-7. Crossref

10. Navarro O, Dugougeat F, Kornecki A, Shuckett B, Alton DJ,

Daneman A. The impact of imaging in the management of

intussusception owing to pathologic lead points in children.

A review of 43 cases. Pediatr Radiol 2000;30:594-603. Crossref

11. Komadina R, Smrkolj V. Intussusception after blunt

abdominal trauma. J Trauma 1998;45:615-6. Crossref

12. Stockinger ZT, McSwain N Jr. Intussusception caused by

abdominal trauma: case report and review of 91 cases

reported in the literature. J Trauma 2005;58:187-8. Crossref

13. Türkyilmaz Z, Sönmez K, Demiroğullari B, et al. Postoperative

intussusception in children. Acta Chir Belg 2005;105:187-9.

14. Emil S, Shaw X, Laberge JM. Post-operative colocolic

intussusception. Pediatr Surg Int 2003;19:220-2.

15. Reijnen JA, Festen C, Joosten HJ, van Wieringen PM.

Atypical characteristics of a group of children with

intussusception. Acta Paediatr Scand 1990;79:675-9. Crossref

16. Hernandez JA, Swischuk LE, Angel CA. Validity of plain

films in intussusception. Emerg Radiol 2004;10:323-6.

17. Ratcliffe JF, Fong S, Cheong I, O’Connell P. The plain

abdominal film in intussusception: the accuracy and incidence

of radiographic signs. Pediatr Radiol 1992;22:110-1. Crossref

18. Bhisitkul DM, Listernick R, Shkolnik A, et al. Clinical

application of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of

intussusception. J Pediatr 1992;121:182-6. Crossref

19. Peh WC, Khong PL, Lam C, et al. Reduction of

intussusception in children using sonographic guidance.

AJR Am J Roentgenol 1999;173:985-8. Crossref

20. Lui KW, Wong HF, Cheung YC, et al. Air enema for

diagnosis and reduction of intussusception in children:

clinical experience and fluoroscopy time correlation. J

Pediatr Surg 2001;36:479-81. Crossref

21. Rubí I, Vera R, Rubí SC, et al. Air reduction of

intussusception. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2002;12:387-90. Crossref

22. Hadidi AT, El Shal N. Childhood intussusception: a

comparative study of nonsurgical management. J Pediatr

Surg 1999;34:304-7. Crossref

23. Schier F. Experience with laparoscopy in the treatment of

intussusception. J Pediatr Surg 1997;32:1713-4. Crossref

24. Poddoubnyi IV, Dronov AF, Blinnikov OI, Smirnov AN,

Darenkov IA, Dedov KA. Laparoscopy in the treatment of

intussusception in children. J Pediatr Surg 1998;33:1194-7. Crossref

25. Waseem M, Rosenberg HK. Intussusception. Pediatr

Emerg Care 2008;24:793-800. Crossref

26. Bruce J, Huh YS, Cooney DR, Karp MP, Allen JE, Jewett

TC Jr. Intussusception: evolution of current management. J

Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1987;6:663-74. Crossref

27. Losek JD. Intussusception: don’t miss the diagnosis! Pediatr

Emerg Care 1993;9:46-51. Crossref

28. Stringer DA, Ein SH. Pneumatic reduction: advantages,

risks and indications. Pediatr Radiol 1990;20:475-7. Crossref

29. Meyer JS, Dangman BC, Buonomo C, Berlin JA. Air and

liquid contrast agents in the management of intussusception:

a controlled, randomized trial. Radiology 1993;188:507-11. Crossref

30. Daneman A, Alton DJ, Ein S, Wesson D, Superina R,

Thorner P. Perforation during attempted intussusception

reduction in children—a comparison of perforation with

barium and air. Pediatr Radiol 1995;25:81-8. Crossref