Hong Kong Med J 2015 Oct;21(5):435–43 | Epub 15 Sep 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144385

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Intensive care unit family satisfaction survey

SM Lam, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)1;

HM So, MN, MSc1;

SK Fok, MN1;

SC Li, RN, MN1;

CP Ng, BSN1;

WK Lui, RN1;

DK Heyland, MSc, MD2;

WW Yan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)1

1 Department of Intensive Care, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

2 Department of Medicine, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada

Full

paper in PDF

Full

paper in PDF

Corresponding author: Dr SM Lam (lamsm2@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Objectives: To examine the level of family satisfaction

in a local intensive care unit and its performance in

comparison with international standards, and to

determine the factors independently associated with

higher family satisfaction.

Design: Questionnaire survey.

Setting: A medical-surgical adult intensive care unit

in a regional hospital in Hong Kong.

Participants: Adult family members of patients

admitted to the intensive care unit for 48 hours or

more between 15 June 2012 and 31 January 2014,

and who had visited the patient at least once during

their stay.

Results: Of the 961 eligible families, 736

questionnaires were returned (response rate, 76.6%).

The mean (± standard deviation) total satisfaction

score, and subscores on satisfaction with overall

intensive care unit care and with decision-making

were 78.1 ± 14.3, 78.0 ± 16.8, and 78.6 ± 13.6,

respectively. When compared with a Canadian

multicentre database with respective mean scores of

82.9 ± 14.8, 83.5 ± 15.4, and 82.6 ± 16.0 (P<0.001),

there was still room for improvement. Independent

factors associated with complete satisfaction with

overall care were concern for patients and families,

agitation management, frequency of communication by nurses, physician skill and competence, and

the intensive care unit environment. A performance-importance

plot identified the intensive care unit

environment and agitation management as factors

that required more urgent attention.

Conclusions: This is the first intensive care unit

family satisfaction survey published in Hong Kong.

Although comparable with published data from

other parts of the world, the results indicate room

for improvement when compared with a Canadian

multicentre database. Future directions should focus

on improving the intensive care unit environment,

agitation management, and communication with

families.

New knowledge added by this

study

- This study provides the first dataset on the level of family satisfaction with intensive care unit (ICU) care in Hong Kong.

- Factors that independently affected family satisfaction include the ICU environment, agitation management, and communication between health care workers and families. These are all potentially amenable to improvement.

- Factors identified to be independently associated with higher family satisfaction will provide directions for future improvement.

- Such baseline data will allow for assessment of the efficacy of future improvement initiatives.

Introduction

Providing professional care and establishing a good

rapport with patients is the mission of all health

care workers. This relationship building is part

of the patient-centred health care delivery model

that is currently being advocated over a clinician- or

disease-centred model.1 It is associated with

better clinical outcomes and may reduce potential

complaints due to miscommunication.2 3 4 In the intensive care setting where patients often cannot

make their own decisions, either due to their illness

or to the effect of medications,5 building a good

relationship with the patients’ family is especially

important. Furthermore, it has been recognised that

families of patients admitted to the intensive care

unit (ICU) are at higher risk of developing anxiety,

depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.6 7

They are suddenly subjected to an uncertain outcome

for their loved ones, with associated emotional,

social and financial consequences, and in a strange

environment packed with complex technological

advancements. The long-term psychological impact

on the family after an ICU encounter is now termed

as post-intensive care syndrome–family (PICS-F).7

This adds to the society’s health care burden and

reduces the family ability to provide care. Evidence

suggests that the risk of developing PICS-F is

affected by the manner in which health care workers

interact with the family.8 For these reasons, ICU

quality measurement should include the families’

perspective and their satisfaction with the care

process.9 10

In early 2012, the Department of Intensive

Care, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital,

Hong Kong (PYNICU) initiated the Family

Satisfaction Enhancement (FAME) programme

that aimed to improve family satisfaction with ICU

care. A regular satisfaction survey was performed

that intended to identify problem areas and make

subsequent improvements. The current study was

part of the FAME programme that evaluated the level

of family satisfaction in a local ICU and its performance

in comparison with international standards, and

determined factors that are independently associated

with a higher family satisfaction and could be used to

plan future initiatives.

Methods

This was a questionnaire survey carried out at

PYNICU, which is a mixed medical-surgical 22-bed

adult ICU in a regional hospital with 1633 beds

in Hong Kong. It is a closed ICU with 24-hour

intensivist coverage.

The Family Satisfaction in the ICU (FS-ICU)

questionnaire is a patient family satisfaction

questionnaire originally developed in 2003 by a

group of health care professionals in Canada: the

Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network

(CARENET).5 The questionnaire has been validated

for use in North America and Europe,11 12 13 14 and has

been translated into other languages including

Chinese. The questionnaire is accessible online

(http://www.thecarenet.ca). The questionnaire

consists of 37 items in two parts: satisfaction with

overall ICU care, and satisfaction with decision-making

around the care of critically ill patients; and

three open-ended questions. Respondents were

asked to provide baseline data (sex, age, relationship

with the patient, prior experience with ICU, and

whether they lived together before admission) at the

start of the questionnaire. Corresponding patient

data were retrieved from the Clinical Management

System, electronic Patient Record, and Clinical Data

Analysis and Reporting System.

Patients who were admitted to the ICU for 48

hours or more between 15 June 2012 and 31 January

2014, and were visited by their next-of-kin (NOK;

defined as the key contact person nominated by

the family and documented on the nursing chart on

admission) during their stay in the ICU were eligible.

Once an eligible patient was nearing ICU discharge

(defined as an expected date of ICU discharge

within the next 5 days as judged each morning

by a senior clinician or nurse consultant), or had

passed away in the ICU, his/her NOK was invited

by an independent research assistant not involved in

clinical care to participate in the survey. A minimum

stay of 48 hours was used as in previous studies

to ensure an adequate exposure of families to the

ICU.15 16 A copy of the questionnaire and an envelope were given to the NOK to be completed based on

his/her opinion. He/she was asked to return the

questionnaire in the envelope provided, which was

opened only by researchers. Those who failed to

return the questionnaire were contacted by phone

within 2 months of ICU discharge or death, and

the questionnaire was sent to them with a stamped

addressed envelope if they agreed to participate. All

respondents were ensured of the confidentiality and

anonymity of their response. For patients who were

admitted to the ICU more than once within the same

hospitalisation, only the last was analysed.

The study protocol was reviewed by the Hong

Kong East Cluster Ethics Committee and the need

for consent was waived.

Statistical analyses

Items in the FS-ICU questionnaire were scored as previously

described12: each item was recoded into a linear

scale ranging from 0 to 100, with 0 as very poor or

very dissatisfied, and 100 as excellent or completely

satisfied. Three items (“received appropriate amount

of information”, “had enough time to think in decision-making

process”, and “adequate time to address

concerns and answer questions”) were recoded into

dichotomous variables, while two items (“involved

at right time in decision-making process”, and “given

right amount of hope patient would recover”) were

recoded into a 3-point Likert scale.12 A mean (± standard

deviation [SD]) score was computed for each item.

Subscores for satisfaction with overall ICU care

(FS-ICU/Care) and satisfaction with role in decision-making

(FS-ICU/DM), and a total score (FS-ICU/Total) were generated by averaging available items,

provided that the respondent answered 70% or more

of the items in the respective sections.12

Results were compared using Mann-Whitney

U test with those of a multicentre Canadian database

(written communication, Daren Heyland, Feb 2014) that comprised data captured

from 2003 to 2006 at 12 Canadian sites.

Univariate analyses of satisfaction with overall

ICU care and satisfaction with role in decision-making

were conducted. Variables included the

baseline respondent’s and patient’s characteristics,

as well as items of part 1 or part 2 of FS-ICU,

respectively. Continuous variables were categorised

using their median, and questionnaire items were

categorised into “completely satisfied” and “less than

completely satisfied”. Factors with a P value of ≤0.1

were entered into multivariable logistic regression

using stepwise backward elimination to identify

independent factors associated with complete

family satisfaction with overall ICU care and role in

decision-making.

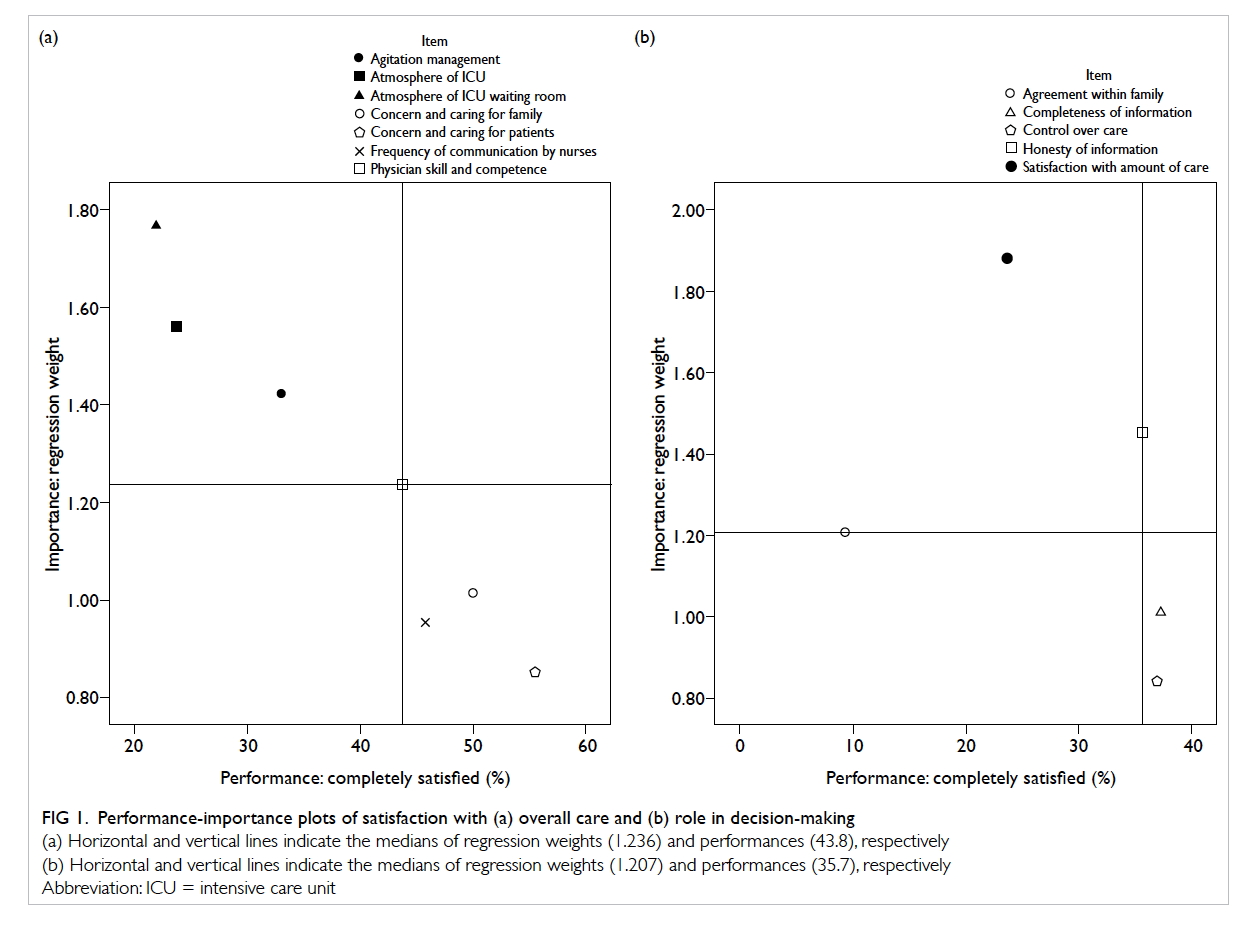

The independent factors thus identified by

multivariable logistic regression were used in the

construction of performance-importance plots to

identify those factors that deserve more urgent

attention because of their higher importance

(regression weights above the median) but lower

performance (percentage of that item being rated as

“excellent” being below the median).

By applying the rule of 10 on logistic regression

analysis of family satisfaction with overall ICU care,

a target sample size was estimated to be 725 with

29 covariates with an estimated 40% of respondents

being “completely satisfied” with overall care. All tests

were two-sided, and a P value of <0.05 was considered

statistically significant. All data were analysed

using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

(Windows version 20; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US).

Results

From 15 June 2012 to 31 January 2014, 961 patients

were eligible and 822 families agreed to participate;

736 questionnaires were eventually returned,

with a response rate of 76.6%. Excluding the three

questions only applicable to families of patients

who passed away in ICU and the three open-ended

questions, 23 766 (95.0%) of the total 25 024

questions were completed. Baseline characteristics

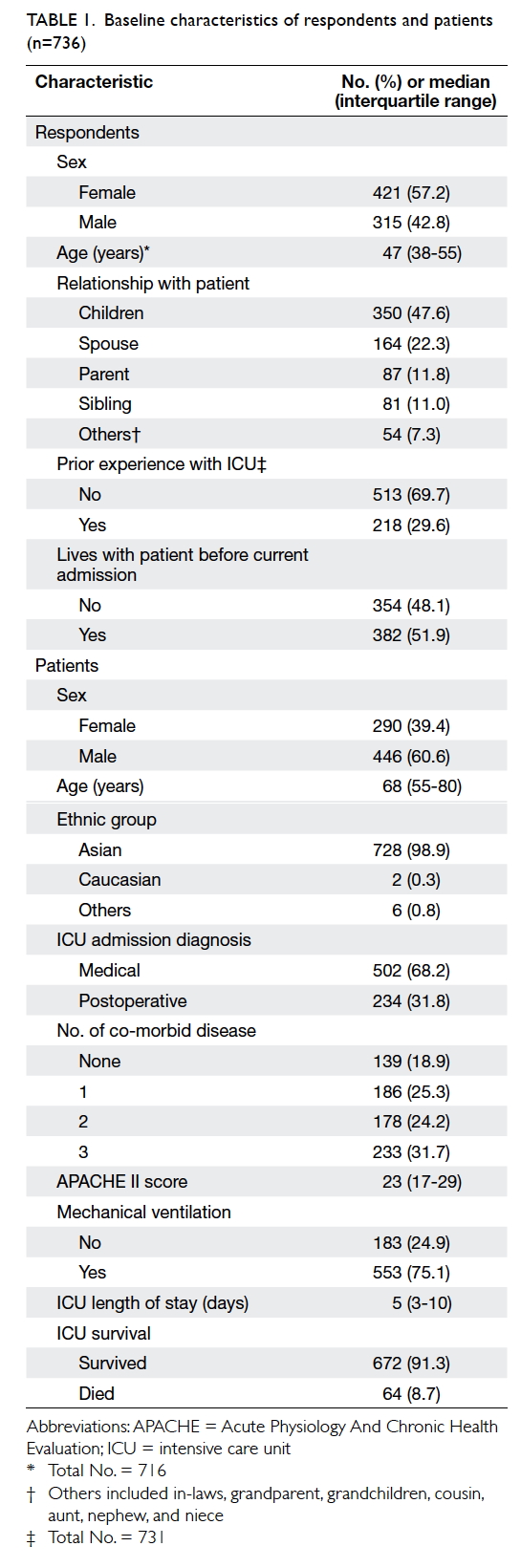

of the respondents and patients are shown in Table 1.

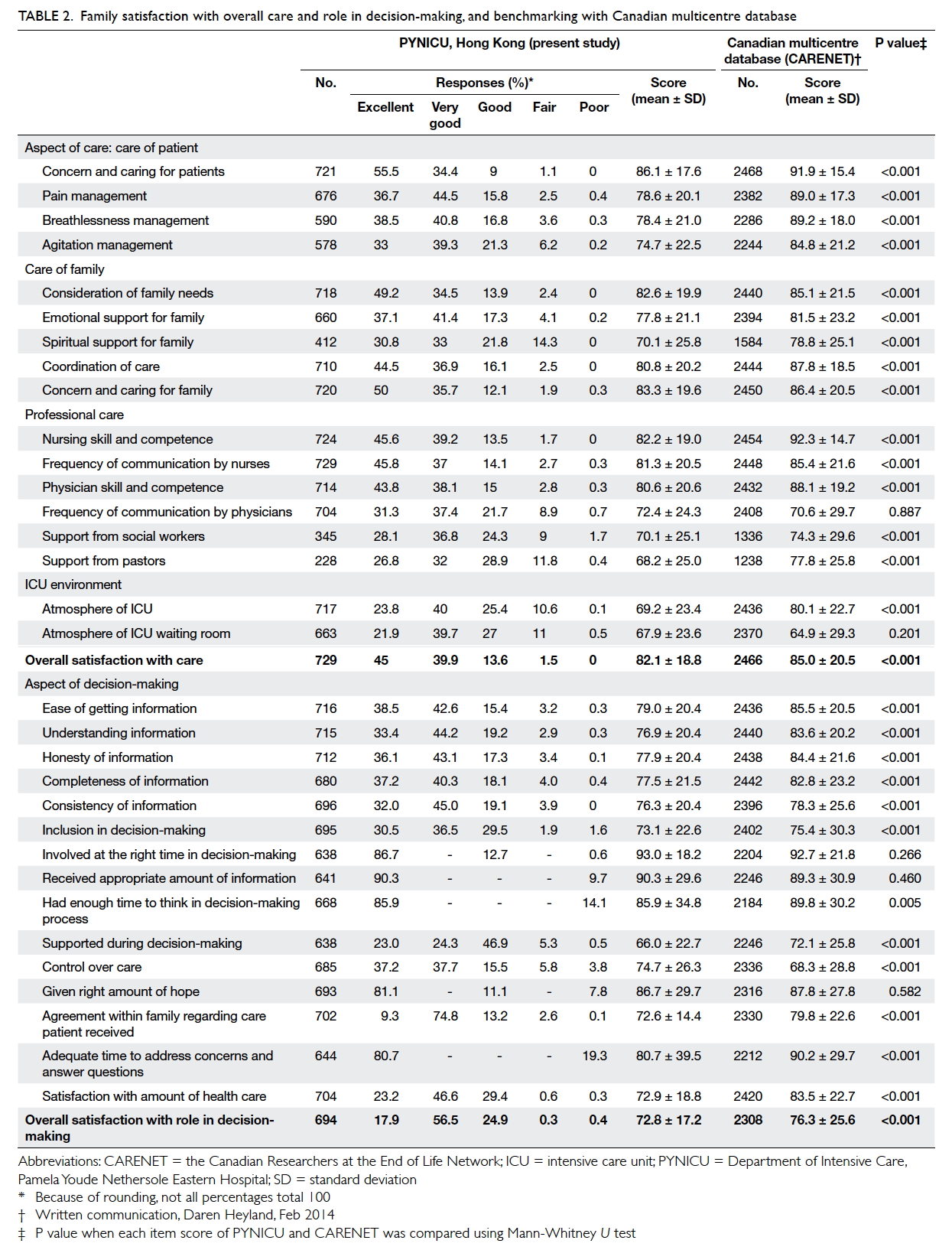

Our mean (± SD) FS-ICU/Total, FS-ICU/Care,

and FS-ICU/DM scores were 78.1 ± 14.3, 78.0 ±

16.8, and 78.6 ± 13.6, respectively. Table 2 shows the percentage of responses and mean score for each

questionnaire item.

Table 2. Family satisfaction with overall care and role in decision-making, and benchmarking with Canadian multicentre database

When results were compared with the

Canadian data (written communication, Daren Heyland, Feb 2014), the latter had a higher mean FS-ICU/Total, FS-ICU/Care, and FS-ICU/DM score of 82.9

± 14.8, 83.5 ± 15.4, and 82.6 ± 16.0, respectively

(P<0.001 for all three scores when compared with

PYNICU). Table 2 shows the result for each FS-ICU item; PYNICU achieved a significantly higher

mean score for item “control over care”. There was

no significant difference in scores between the two

databases for items “frequency of communication by physicians”,

“atmosphere of ICU waiting room”, “involved at the

right time in decision-making”, “received appropriate

amount of information”, and “given right amount of

hope”. The Canadian sites achieved higher scores for

the remaining items.

In the univariate analysis of satisfaction

with overall ICU care, none of the patient’s or

respondent’s characteristics had a P≤0.1. Items

“spiritual support for family”, “support from social

workers”, and “support from pastors” were excluded

since more than 30% of the responses were either

missing or deemed not applicable. Thus, a total of

14 covariates were analysed in the multivariable

analysis. The independent factors identified

were “concern and caring for patients”, “agitation

management”, “concern and caring for family”,

“frequency of communication by nurses”, “physician skill and

competence”, “atmosphere of ICU”, and “atmosphere

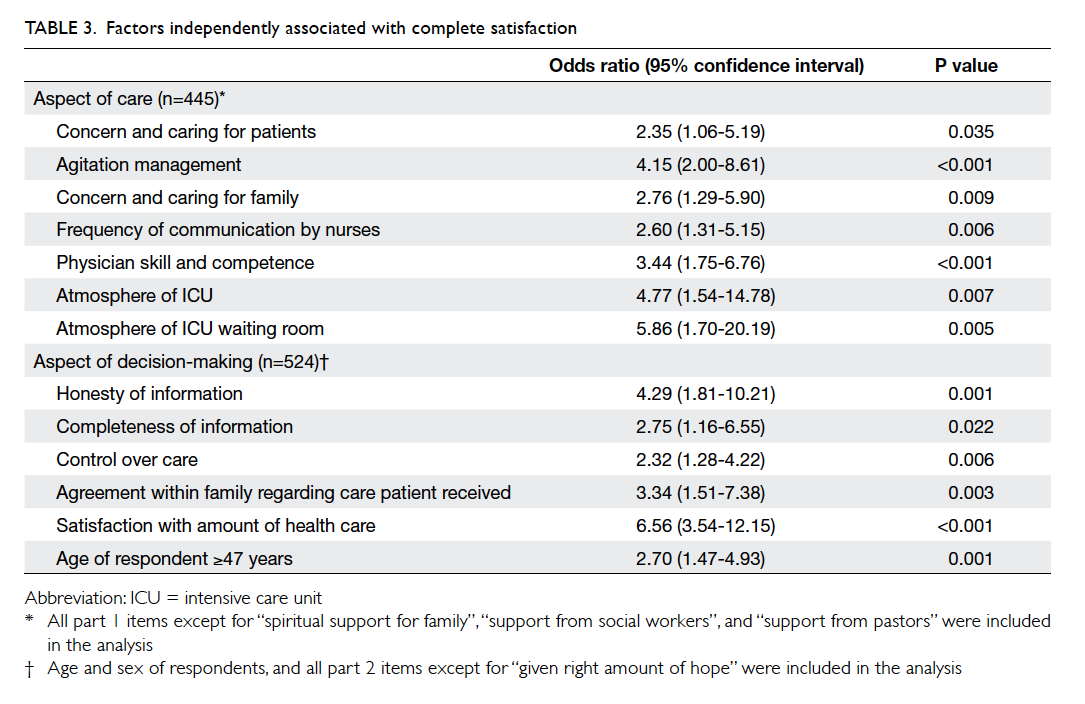

of ICU waiting room” (Table 3). In the multivariable analysis of satisfaction with role in decision-making,

16 covariates including “age of respondent”, “sex

of respondent” (with P values of 0.005 and 0.08,

respectively in the univariate analysis), and all items

in part two of the questionnaire excluding item

“given right amount of hope” (P=0.214 in univariate

analysis) were tested. Independent factors identified

were “honesty of information”, “completeness of

information”, “control over care”, “agreement within

family regarding care patient received”, “satisfaction

with amount of health care”, and “age of respondent

≥47 years” (Table 3).

Performance-importance plots identified

the following items as being more important but

performed less satisfactorily: “atmosphere of ICU

waiting room”, “atmosphere of ICU”, “agitation

management” (overall care), and “satisfaction

with amount of health care”

(decision-making) [Fig 1].

Figure 1. Performance-importance plots of satisfaction with (a) overall care and (b) role in decision-making

(a) Horizontal and vertical lines indicate the medians of regression weights (1.236) and performances (43.8), respectively

(b) Horizontal and vertical lines indicate the medians of regression weights (1.207) and performances (35.7), respectively

Discussion

This is the first ICU family satisfaction survey

published in Hong Kong, and was conducted

following implementation of the FAME programme

in 2012. Following a small-scale survey carried out by

PYNICU in 2010 (written communication, HL Wu,

2012), staff awareness about the importance of family

satisfaction has increased. Family satisfaction was

added to the regular agenda at our weekly business

meetings, where comments and feedback from NOKs

were discussed. These discussions led to various

measures to improve communication (unsolicited

nurses’ update during visiting hours), access to

information (information booklets in waiting rooms

and noticeboard displays for families), and facilities

(chairs for families at bedside, televisions for awake

patients, and refurbishment of the waiting rooms).

This survey showed high satisfaction scores in 2012 to

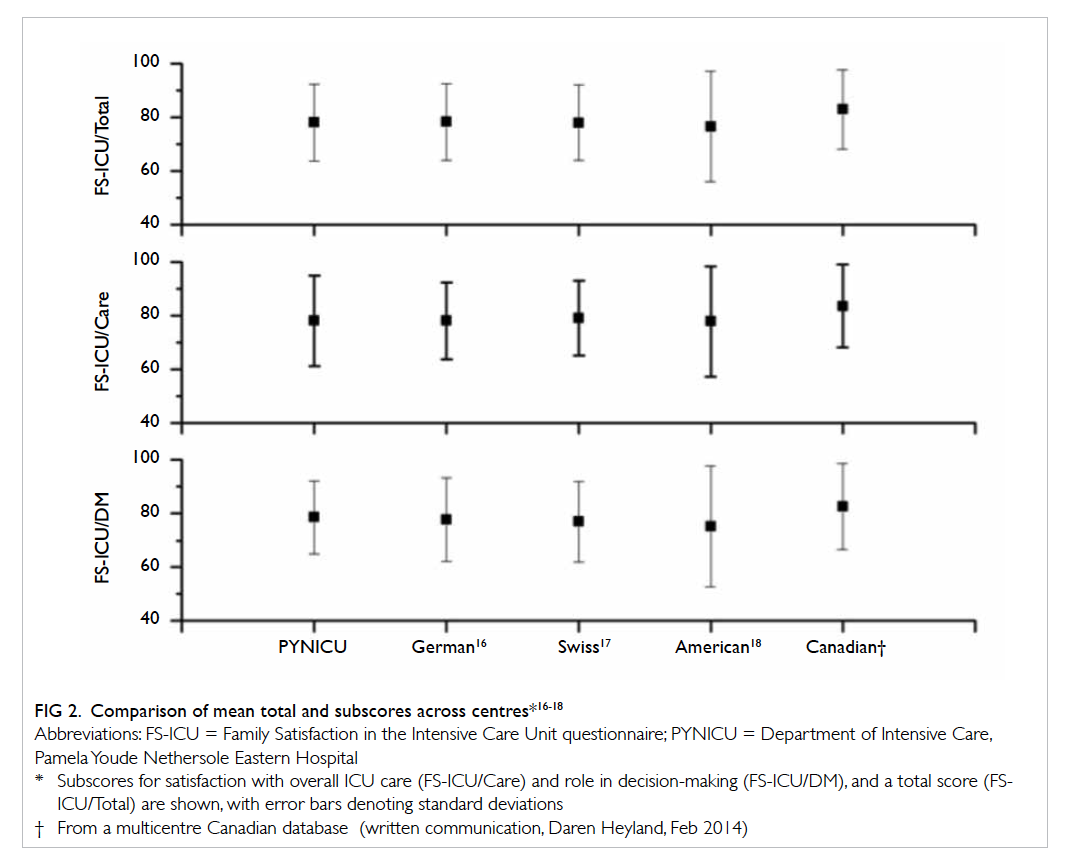

2014 that were similar to figures reported around the

world (Fig 2 16 17 18 as well as the multicentre Canadian database—a German study reported their

mean FS-ICU/Total, FS-ICU/Care, and FS-ICU/DM

as 78.3 ± 14.3, 78.6 ± 14.3, and 77.8 ± 15.616; a Swiss

study reported scores of 78 ± 14, 79 ± 14, and 77 ±

1517; and an American study achieved scores of 76.6

± 20.6, 77.7 ± 20.6, and 75.2 ± 22.6, respectively.18

Nonetheless the Canadian centres were able to

achieve a significantly better result in most items and

in the summary scores. This might be explained by

cross-cultural (different expectations from families),

as well as administrative differences (nurse-patient

and doctor-patient ratios), but it may also indicate

room for further improvement.

Independent factors that affected satisfaction

with overall care and identified by this study can be

grouped into: care of the patient and family (concern

and caring for the patient and family; agitation

management), professional care (frequency of communication by nurses; physician skill and competence),

and the ICU environment (atmosphere of the ICU

and its waiting room). Consistent with prior studies,

none of the patient’s or respondent’s characteristics,

including the ICU survival status, was found to be

independently associated with satisfaction of overall

care.16 19 Setting professional skills aside, the perceived

physician competence and amount of concern and

care shown to patients and their families were largely

affected by the communication skill of the health

care providers and their manner when interacting

with patients and families. The importance of

communication has been emphasised by numerous

studies.20 21 22 23 24 25 One study found that longer periods of communication between health care providers and

families was associated with reduced anxiety among

family members of ICU patients.24 They reported

a median (range) time of staff contact as 10 (1-60)

minutes. In addition to the duration, a proactive,

structured, and multidisciplinary communication

strategy that incorporated the five objectives in

the mnemonic “VALUE” (to Value and appreciate

what the family members said, to Acknowledge the

family members’ emotions, to Listen, to ask open-ended

questions that would allow the caregiver to

Understand who the patient was as a person, and to

Elicit questions from family members) was shown to

lessen symptoms of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic

stress disorder.25 Education and training

in communication skills, especially the power of

listening and to allow families more opportunity

to speak during conferences also improved family

satisfaction in the ICU.26 It is also essential to

diagnose the root cause of any communication

problem.15 Removing barriers in the health care

system that discourage communication, for example

heavy workload rendering insufficient time spent

with families and restrictive visiting policies, would

be beneficial.27

Factors in the left upper quadrant of the

performance-importance plots (Fig 1) had greater

regression weights but performed less satisfactorily,

and therefore warrant more urgent attention. Among

these were the ICU and waiting room environment.

The questionnaire items do not specify the particular

areas of concern that individual families had in mind,

but responses to the three open-ended questions

were illuminating. Comments related to the ICU

environment focused on the availability of facilities

for patients (visual and audio entertainment devices)

and their families (chairs and toilet), ICU noise level,

room temperature, space, and privacy. In fact, the

ICU environment has been repeatedly identified as a

factor that affects satisfaction.13 18 19 One study found that migration of an ICU with multiple beds in one

ward to another with single-room design significantly

improved family and patient satisfaction.13 These

findings offer opportunities for improvement, and

also provide valuable information for administrators

when designing a new ICU.

Agitation management also warranted more

urgent attention (Fig 1a). Although evidence

supports maintenance of a light rather than deep

level of sedation in adult critically ill patients to

shorten duration of mechanical ventilation and

ICU length of stay,28 29 a balance needs to be struck

to prevent excessive pain, agitation, or adverse

experiences that are associated with a higher

incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder in

ICU survivors and could negatively impact their

families.30 The revised 2013 version of Clinical

Practice Guidelines for the Management of Pain,

Agitation, and Delirium in Adult ICU Patients has

recommended routine monitoring of the depth of

sedation and targeted titration of preferably non-benzodiazepine

sedatives.31

Our subscore for decision-making was higher

than that for overall care, in contrast to the overseas

counterparts.16 17 18 We do not know if this is unique to the Chinese population since no other Chinese

survey is available for comparison. One interesting

finding was that younger respondents were less

satisfied with their role in decision-making than

older respondents. A similar observation has been

made before.32 In this information explosion era

where electronic data are easily available, it can be

understood that the younger generation wants to

play a greater role in making decisions for their sick

family member. A paternalistic approach will be less

appealing to our future generation, and a deliberative

model should therefore be adopted, with an emphasis

on provision of complete and honest information to

increase their sense of control over the care of their

family member.

There are limitations to our study. First, the

reason for refusal to participate in the survey was

not documented and therefore we cannot rule out

a response bias, where dissatisfied families might

have declined participation in the survey, thus

overestimating satisfaction. The high return rate

compared with other studies (76.6% vs 27.8-75.4%15 16 17)

would have lessened any effect of a response bias.

Second, social desirability bias cannot be ruled out

as most respondents completed the questionnaire

while their sick family member was still under

our care. We tried to minimise this by reassuring

families of the confidentiality of their response

and providing an envelope in which to return the

completed questionnaire that was only opened by

researchers at a later time. Third, questionnaires

completed before ICU discharge might not reflect

the whole ICU experience. Recruiting NOKs when

the patient was nearing ICU discharge reduced

premature data capture and prevented the otherwise

increased administrative cost, increased recall bias,

and anticipated lower response rate that would be

involved when tracing eligible NOKs following ICU

discharge. Fourth, FS-ICU has not been validated

in the Chinese language. The Chinese (Taiwan)

version provided by CARENET was modified by the

co-authors wherein Taiwanese terms were replaced

by ones familiar to the Hong Kong people and

questions on the respondent’s demographics were

added as in the original English questionnaire. This

modified version was circulated to and approved by

all co-authors to ensure face validity. The high return

rate of the questionnaire and the high response rate

to questions (95.0%) indicated feasibility of this

modified Chinese version.11 Last, this was a single-centre

study and thus generalisability of the results

to other settings may not be appropriate.

Conclusions

Family satisfaction is an important measure of ICU

quality. We found that families were satisfied with

the ICU care we provided and with their role in

decision-making. Their satisfaction was comparable

with most overseas centres. Nonetheless there

remains room for improvement when compared

with the Canadian database. Future initiatives will

focus on improving the ICU environment, agitation

management, and enhancing communication with

families.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all members of the FAME team

including Dr Arthur CW Lau, Ms Nora LP Kwok,

Ms L Lau, Ms CH Lee, and Ms HY Wong for their

administrative advice and contribution in data

collection and entry, and Ms CH Li, Ms WY So,

and Ms PS Chiu for subject recruitment. We also

wish to thank the Canadian Researchers at the End of

Life Network for sharing their FS-ICU database.

Current versions of the FS-ICU questionnaire can

be found on their website <www.thecarenet.ca/57-researchers/our-projects/family-satisfaction-survey>.

References

1. Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, et al. Clinical

practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered

intensive care unit: American College of Critical

Care Medicine Task Force 2004-2005. Crit Care Med

2007;35:605-22. Crossref

2. Lewin SA, Skea ZC, Entwistle V, Zwarenstein M, Dick J.

Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred

approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev 2001;(4):CD003267. Crossref

3. Roter DL, Hall JA, Kern DE, Barker LR, Cole KA, Roca

RP. Improving physicians’ interviewing skills and reducing

patients’ emotional distress. A randomized clinical trial.

Arch Intern Med 1995;155:1877-84. Crossref

4. Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered

care on outcomes. J Fam Pract 2000;49:796-804.

5. Heyland DK, Tranmer JE; Kingston General Hospital ICU

Research Working Group. Measuring family satisfaction

with care in the intensive care unit: the development

of a questionnaire and preliminary results. J Crit Care

2001;16:142-9. Crossref

6. Sundararajan K, Martin M, Rajagopala S, Chapman MJ.

Posttraumatic stress disorder in close relatives of intensive

care unit patients’ evaluation (PRICE) study. Aust Crit

Care 2014;27:183-7. Crossref

7. Schmidt M, Azoulay E. Having a loved one in the ICU: the

forgotten family. Curr Opin Crit Care 2012;18:540-7. Crossref

8. Davidson JE, Jones C, Bienvenu J. Family response to

critical illness: postintensive care syndrome-family. Crit

Care Med 2012;40:618-24. Crossref

9. Flaatten H. The present use of quality indicators in the

intensive care unit. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2012;56:1078-83. Crossref

10. de Vos M, Graafmans W, Keesman E, Westert G, van der

Voort PH. Quality measurement at intensive care units:

which indicators should we use? J Crit Care 2007;22:267-74. Crossref

11. Stricker KH, Niemann S, Bugnon S, Wurz J, Rohrer O,

Rothen HU. Family satisfaction in the intensive care unit:

cross-cultural adaptation of a questionnaire. J Crit Care

2007;22:204-11. Crossref

12. Wall RJ, Engelberg RA, Downey L, Heyland DK, Curtis

JR. Refinement, scoring, and validation of the family

satisfaction in the intensive care unit (FS-ICU) survey. Crit

Care Med 2007;35:271-9. Crossref

13. Jongerden IP, Slooter AJ, Peelen LM, et al. Effect of intensive

care environment on family and patient satisfaction: a

before-after study. Intensive Care Med 2013;39:1626-34. Crossref

14. Tastan S, Iyigun E, Ayhan H, Kilickaya O, Yilmaz AA,

Kurt E. Validity and reliability of Turkish version of family

satisfaction in the intensive care unit. Int J Nurs Pract

2014;20:320-6. Crossref

15. Heyland DK, Rocker GM, Dodek PM, et al. Family

satisfaction with care in the intensive care unit: results of a

multiple center study. Crit Care Med 2002;30:1413-8. Crossref

16. Schwarzkopf D, Behrend S, Skupin H, et al. Family

satisfaction in the intensive care unit: a quantitative and

qualitative analysis. Intensive Care Med 2013;39:1071-9. Crossref

17. Stricker KH, Kimberger O, Schmidlin K, Zwahlen M,

Mohr U, Rothen HU. Family satisfaction in the intensive

care unit: what makes the difference? Intensive Care Med

2009;35:2051-9. Crossref

18. Osborn TR, Curtis JR, Nielsen EL, Back AL, Shannon

SE, Engelberg RA. Identifying elements of ICU care

that families report as important but unsatisfactory:

decision-making, control, and ICU atmosphere. Chest

2012;142:1185-92. Crossref

19. Hunziker S, McHugh W, Sarnoff-Lee B, et al. Predictors

and correlates of dissatisfaction with intensive care. Crit

Care Med 2012;40:1554-61. Crossref

20. Scheunemann LP, McDevitt M, Carson SS, Hanson LC.

Randomized, controlled trials of interventions to improve

communication in intensive care: a systematic review.

Chest 2011;139:543-54. Crossref

21. Kodali S, Stametz RA, Bengier AC, Clarke DN, Layon AJ,

Darer JD. Family experience with intensive care unit care:

association of self-reported family conferences and family

satisfaction. J Crit Care 2014;29:641-4. Crossref

22. Lily CM, De Meo DL, Sonnar LA, et al. An intensive

communication intervention for the critically ill. Am J Med

2000;109:469-75. Crossref

23. Shelton W, Moore CD, Socaris S, Gao J, Dowling J.

The effect of a family support intervention on family

satisfaction, length-of-stay, and cost of care in the intensive

care unit. Crit Care Med 2010;38:1315-20. Crossref

24. Rusinova K, Kukal J, Simek J, Cerny V; DEPRESS

study working group. Limited family members/staff

communication in intensive care units in the Czech

and Slovak Republics considerably increases anxiety in

patients’ relatives—the DEPRESS study. BMC Psychiatry

2014;14:21. Crossref

25. Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. A

communication strategy and brochure for relatives of

patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med 2007;356:469-78. Crossref

26. McDonagh JR, Elliott TB, Engelberg RA, et al. Family

satisfaction with family conferences about end-of-life care

in the intensive care unit: increased proportion of family

speech is associated with increased satisfaction. Crit Care

Med 2004;32:1484-8. Crossref

27. Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Shannon SE, Treece PD, Engelberg

RA, Rubenfeld GD. The family conference as a focus to

improve communication about end-of-life care in the

intensive care unit: opportunities for improvement. Crit

Care Med 2001;29(2 Suppl):N26-33. Crossref

28. Kress JP, Pohlman AS, O’Connor MF, Hall JB. Daily

interruption of sedative infusions in critically ill patients

undergoing mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med

2000;342:1471-7. Crossref

29. Girard TD, Kress JP, Fuchs BD, et al. Efficacy and safety

of a paired sedation and ventilator weaning protocol

for mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care

(Awakening and Breathing Controlled trial): a randomised

controlled trial. Lancet 2008;371:126-34. Crossref

30. Granja C, Gomes E, Amaro A, et al. Understanding

posttraumatic stress disorder–related symptoms after

critical care: the early illness amnesia hypothesis. Crit Care

Med 2008;36:2801-9. Crossref

31. Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. Clinical practice

guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and

delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit

Care Med 2013;41:263-306. Crossref

32. Crow R, Gage H, Hampson S, et al. The measurement of

satisfaction with healthcare: implications for practice from

a systematic review of the literature. Health Technol Assess

2002;6:1-244. Crossref