DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144321

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Three cases of atypical pneumonia caused by Chlamydophila psittaci

Sandy Chau, MB, BS, FHKAM (Pathology)1;

Eugene YK Tso, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)2;

WS Leung, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)2;

Kitty SC Fung, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Pathology)1

1 Department of Pathology, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

2 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Sandy Chau (chauky@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Psittacosis is a zoonotic disease caused by

Chlamydophila psittaci. The most common

presentation is atypical pneumonia. Three cases of

pneumonia of varying severity due to psittacosis are

described. All patients had a history of avian contact.

The diagnosis was confirmed by molecular detection

of Chlamydophila psittaci in respiratory specimens.

The cases showed good recovery with doxycycline

treatment. Increased awareness of psittacosis

can shorten diagnostic delay and improve patient

outcomes.

Introduction

Psittacosis is a zoonotic disease caused by

Chlamydophila psittaci, an obligate intracellular

pathogen belonging to the family Chlamydiaceae.

Since its first description in 1879, zoonotic

and enzoonotic outbreaks have been reported

worldwide.1 Transmission occurs through direct

contact or inhalation of aerosols from dried faeces,

feather dust, or respiratory secretions of infected

birds. Individuals with occupational or recreational

exposure to birds like bird fanciers and veterinarians

are at greatest risk of infection. Person-to-person

transmission is rare.2 The disease can range from

subclinical infection to fatal pneumonia. Here, we

report three cases of atypical pneumonia caused by

C psittaci in Hong Kong.

Case reports

Case 1

A 62-year-old retired male presented in March 2014

with fever, headache, myalgia, cough, and yellowish

sputum for 6 days. He had underlying diabetes

mellitus, hypertension, gout, and renal impairment.

He visited the local bird market frequently and had

purchased two parrots before onset of symptoms.

The parrots were well all along. On presentation,

he was alert and stable and his temperature was

38.4°C. The oxygen saturation was 96% on room

air. Chest examination revealed left lower zone

crepitations. Chest radiograph showed left lower

zone consolidation. He was suspected of psittacosis

and was treated with ceftriaxone and doxycycline.

His sputum was positive for C psittaci by polymerase

chain reaction (PCR). Nasopharyngeal swab and

sputum were also positive for influenza A virus

subtype H3 by PCR. Oseltamivir was commenced.

He was afebrile the next day and was discharged after

5 days of hospitalisation. Paired serum collected 12

days apart showed rising Chlamydia group titre

from 40 to 80 by complement fixation test (CFT).

The parrots could no longer be traced as the patient’s

son released them.

Case 2

A 55-year-old male construction site worker with

hypertension was admitted in February 2014 with a

1-week history of fever, headache, generalised bone

pain, and cough. He had travelled to Shanwei in

China and bought a live chicken from a wet market

2 weeks earlier. On examination, his vital signs were

stable and had a temperature of 40°C. The oxygen

saturation was 98% on room air. Chest examination

was normal. Chest radiograph showed right upper

zone opacities. He was treated as a case of community-acquired

pneumonia with amoxicillin-clavulanate,

doxycycline, and oseltamivir. Sputum culture

showed growth of commensals only. Nasopharyngeal

aspirate (NPA) was negative for influenza viruses,

Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Chlamydophila

pneumoniae by PCR. Oseltamivir was stopped. His

fever subsided on day 3 and he was discharged after

4 days of hospitalisation. Complement fixation test

of paired sera taken 2 weeks apart showed a rise in

Chlamydia group titre from 20 to 80. Sputum was

retrieved and was positive for C psittaci by PCR.

Case 3

A 42-year-old female chef was hospitalised in

February 2014 with fever, cough, yellowish and

blood-stained sputum, and breathing difficulty for 1

week. She had no underlying illness. One week prior

to her admission, she had travelled to Zhaoqing in

China and bought live goose and chicken from a

wet market. On admission, she was in respiratory

distress and her temperature was 39.2°C. The oxygen

saturation was 90% on 100% supplemental oxygen

via non-rebreathing mask. Chest examination

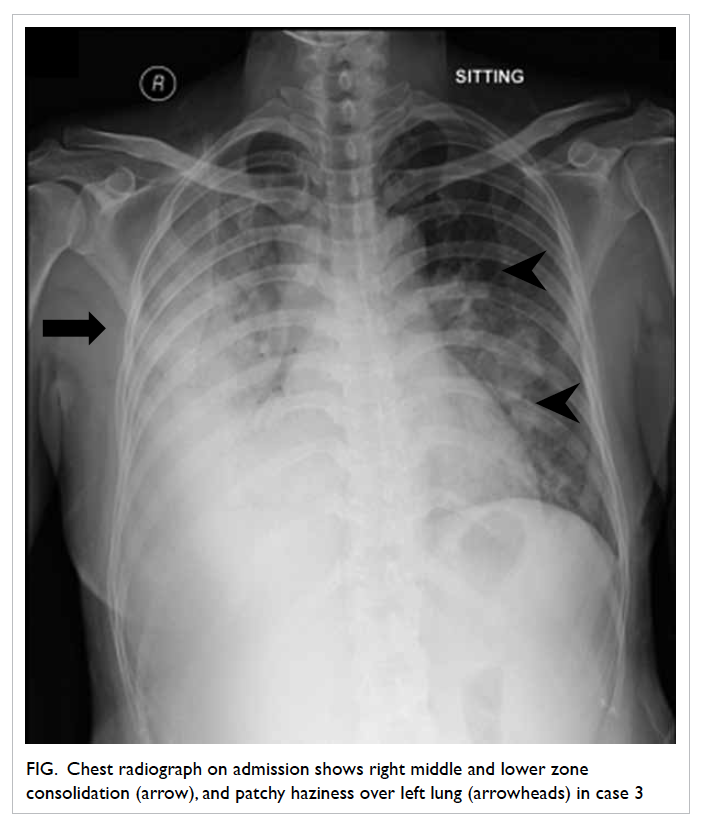

yielded coarse crepitations over the right side. Chest

radiograph revealed right middle and lower zone

consolidation, and left patchy haziness (Fig). On

the same day, she was transferred to the intensive

care unit. She required mechanical ventilation and

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).

She was treated as a case of severe community-acquired

pneumonia with piperacillin-tazobactam,

doxycycline, and oseltamivir. Sputum culture

showed growth of commensals only. Sputum, NPA,

and tracheal aspirate were negative for influenza

viruses, M pneumoniae, and C pneumoniae by PCR.

Urine was negative for Legionella pneumophila and

pneumococcal antigens. She gradually improved

and was extubated 3 days later, and ECMO was

stopped on day 7. She was discharged on day 24 of

hospitalisation. Paired serum drawn 12 days apart

showed rising Chlamydia group titre from 80 to 640

by CFT. Polymerase chain reaction for C psittaci was

positive in her stored sputum.

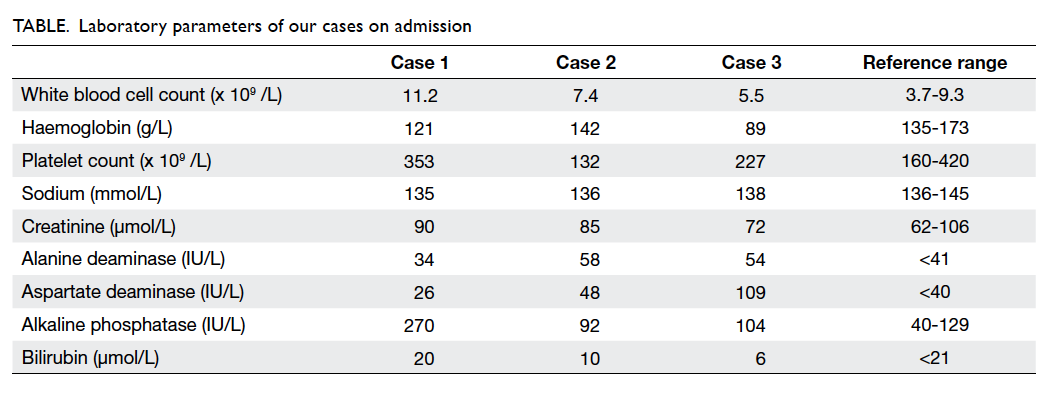

The laboratory profiles of the three cases on

admission are summarised in the Table.

Figure. Chest radiograph on admission shows right middle and lower zone consolidation (arrow), and patchy haziness over left lung (arrowheads) in case 3

Discussion

Psittacosis is an uncommon disease in Hong Kong.

Since 2008, this has been made as a statutory

notifiable disease. There were 11 confirmed cases

and six probable cases reported until 2013.3 In 2012,

there was an outbreak involving six staff working

at the New Territories North Animal Management

Centre in Sheung Shui.4

Chlamydophila psittaci is classified into

nine genotypes (A to F, E/B, M56, WC) based on

outer membrane protein A gene sequences, with

differential host preference and virulence among the

genotypes.1 It has been described in at least 460 bird

species from 30 orders.5 Birds can shed the organisms

when apparently healthy or overtly ill. Patient 1 had

been exposed to asymptomatic parrots, belonging

to the classic culprits, the psittacine birds (parrots,

parakeets, budgerigars, cockatiels). Other domestic

species—for examples, turkey, pigeon, goose, duck,

chicken—can be affected and are often overlooked

as potential reservoirs of infection.6 In patients

2 and 3, psittacosis was not suspected initially

although the patients had been exposed to poultry

in China. Chlamydophila psittaci is an emerging

pathogen among chicken.7 In China, the prevalence

of infection among market-sold chickens, ducks,

and pigeons has been reported to be 13.32%, 38.92%

and 31.09%, respectively.8 The substantial zoonotic

transmission risk from domestic species should also

be recognised.

Psittacosis is a systemic illness that affects

several organ systems, and atypical pneumonia as in

our cases is the most common manifestation. Patients

typically present with influenza-like symptoms,

which include high fever, headache, myalgia, and

dry cough. Patient 3 complained of blood-stained

sputum, which may occur occasionally.1 9 The headaches can be so severe as to suggest meningitis

on presentation. Diarrhoea is common and can be

the chief presenting complaint. Relative bradycardia,

Horder’s spots, and splenomegaly are characteristic

physical signs. There may be disparity between the

auscultatory findings and radiographic changes of

pneumonia. Segmental consolidation in lower lobe

is the most common radiographic abnormality

although normal chest radiograph has been reported

in over 20% of cases. Hilar lymphadenopathy and

pleural effusion are rare.10 The white cell count

is usually normal or slightly raised, with mildly

abnormal liver function. Our case presentations

were consistent with psittacosis. However, it is

indistinguishable clinically from other causes of

atypical pneumonia like C pneumoniae. The severity

ranged from mild-to-severe pneumonia requiring

intensive care management and ECMO in our cases.

Patient 1 had mild illness although co-infected

with influenza A. This diversity of presentation is

in agreement with other case series.9 The mortality

rate can be approximately 15% to 20% without

appropriate treatment but if properly treated, it is

rarely fatal.11 Extrapulmonary complications such as

endocarditis, myocarditis, renal disease, hepatitis,

keratoconjunctivitis, arthritis, and encephalitis have

also been described.

Chlamydophila psittaci is not covered during

routine bacterial or viral workup. Definitive

diagnosis can only be established by culture,

serology, or PCR specifically targeting on C psittaci.

Culture is time-consuming and requires level-3

biosafety facilities. Common serological assays

include CFT, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay,

and microimmunofluorescence (MIF) test. The

assays are neither sensitive nor specific but MIF test

is regarded as more specific.12 However, there are

still considerable cross-reactions between different

species of the Chlamydiaceae family.1 Besides, a

convalescent serum obtained at least 2 weeks apart

is required to demonstrate the 4-fold rise in titre.

In patient 1, the elevation in CFT titre was not

significant and therefore diagnosis may be missed if

relying on serology alone. Early use of doxycycline

in this patient might have blunted the antibody

response.13 In patients 2 and 3, serology results were

available only retrospectively; PCR for C psittaci was

performed subsequently to confirm the diagnosis.

In our cases, a nested PCR based on 16S rRNA

gene was used. The first-step PCR is genus-specific,

followed by the second-step PCR that can detect C

psittaci specifically.14 This method was demonstrated

to be sensitive and specific for detection of C

psittaci. When encountering respiratory illness with

suspicion of psittacosis, PCR testing on respiratory

specimens can offer a rapid and specific diagnosis.

Tetracyclines, in particular doxycycline, are

considered to be the treatment of choice. In patients

presenting with community-acquired pneumonia,

addition of doxycycline to a beta-lactam–based

empirical regimen can provide coverage for

both psittacosis and other atypical pathogens.

Defervescence usually takes place within 48 hours

of treatment. Our patients showed significant

improvement by day 3 of doxycycline treatment. The

commonly recommended duration of treatment is at

least 10 to 21 days to prevent relapse.9 Macrolides

can be used as alternative therapy, but may be

less efficacious in severe cases and gestational

psittacosis.6 Although quinolones have in-vitro

activity against C psittaci, their clinical effectiveness

remains to be determined.6

Conclusion

Psittacosis often goes unrecognised because of the

lack of distinctive symptoms and clinical suspicion.

In patients with atypical pneumonia, a history of

exposure to birds gives a very valuable diagnostic

clue. Early diagnosis with PCR testing and timely

initiation of appropriate antibiotics can reduce

patient morbidity and mortality.

Acknowledgement

We thank the Public Health Laboratory Services

Branch of the Centre for Health Protection for

providing the laboratory testing of psittacosis.

References

1. Beeckman DS, Vanrompay DC. Zoonotic Chlamydophila

psittaci infections from a clinical perspective. Clin

Microbiol Infect 2009;15:11-7. Crossref

2. Hughes C, Maharg P, Rosario P, et al. Possible nosocomial

transmission of psittacosis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol

1997;18:165-8. Crossref

3. Statistics on communicable diseases. Available from:

http://www.chp.gov.hk/en/notifiable1/10/26/43.html. Accessed 25 Feb 2015.

4. Psittacosis outbreak in an animal management centre,

2012. Communicable Diseases Watch 2013;10:9-10.

Available from: http://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/cdw_compendium_2013.pdf. Accessed 25 Feb 2015.

5. Kaleta EF, Taday EM. Avian host range of Chlamydophila

spp. based on isolation, antigen detection and serology.

Avian Pathol 2003;32:435-61. Crossref

6. Stewardson AJ, Grayson ML. Psittacosis. Infect Dis Clin

North Am 2010;24:7-25. Crossref

7. Lagae S, Kalmar I, Laroucau K, Vorimore F, Vanrompay D.

Emerging Chlamydia psittaci infections in chickens and

examination of transmission to humans. J Med Microbiol

2014;63:399-407. Crossref

8. Cong W, Huang SY, Zhang XY, et al. Seroprevalence

of Chlamydia psittaci infection in market-sold adult

chickens, ducks and pigeons in north-western China. J

Med Microbiol 2013;62:1211-4. Crossref

9. Yung AP, Grayson ML. Psittacosis—a review of 135 cases.

Med J Aust 1988;148:228-33.

10. Coutts II, Mackenzie S, White RJ. Clinical and radiographic

features of psittacosis infection. Thorax 1985;40:530-2. Crossref

11. Smith KA, Campbell CT, Murphy J, Stobierski MG,

Tengelsen LA. Compendium of measures to control

Chlamydophila psittaci (formerly Chlamydia psittaci)

infection among humans (psittacosis) and pet birds (avian

chlamydiosis), 2010 National Association of State Public

Health Veterinarians (NASPHV). J Exotic Pet

Med 2011;20:32-45. Crossref

12. Petrovay F, Balla E. Two fatal cases of psittacosis caused by

Chlamydophila psittaci. J Med Microbiol 2008;57:1296-8. Crossref

13. Heddema ER, van Hannen EJ, Duim B, et al. An outbreak

of psittacosis due to Chlamydophila psittaci genotype

A in a veterinary teaching hospital. J Med Microbiol

2006;55:1571-5. Crossref

14. Messmer TO, Skelton SK, Moroney JF, Daugharty H, Fields

BS. Application of a nested, multiplex PCR to psittacosis

outbreaks. J Clin Microbiol 1997;35:2043-6.