Hong Kong Med J 2014 Oct;20(5):413–20 | Epub 1 Aug 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134202

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

The needs of parents of children with visual impairment studying in mainstream schools in Hong Kong

Florence MY Lee, FHKCPaed, FHKAM (Paediatrics); Janice FK Tsang, MSocSc; Mandy MY Chui, MSc

Child Assessment Service, Department of Health, 2/F, 147L Argyle Street, Kowloon City, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Florence MY Lee (florence_lee@dh.gov.hk)

Abstract

Objectives: This study attempted to use a validated

and standardised psychometric tool to identify the

specific needs of parents of children with visual impairment studying in mainstream schools in Hong

Kong. The second aim was to compare their needs

with those of parents of mainstream school children

without special education needs and parents having

children with learning and behavioural problems.

Design: Cross-sectional survey.

Setting: Mainstream schools in Hong Kong.

Participants: Parents of 30 children with visual

impairment who were studying in mainstream

schools and attended assessment by optometrists at

Child Assessment Service between May 2009 and June

2010 were recruited in the study (visual impairment

group). Parents of 45 children with learning and

behavioural problems recruited from two parent

support groups (learning and behavioural problems

group), and parents of 233 children without special

education needs studying in mainstream schools

recruited in a previous validation study on Service

Needs Questionnaire (normal group) were used for

comparison. Participants were invited to complete a

self-administered Service Needs Questionnaire and

a questionnaire on demographics of the children

and their responding parents. The visual impairment

group was asked additional questions about the

ability of the child in coping and functioning in academic and recreational activities.

Results: Needs expressed by parents of the visual

impairment group were significantly higher than

those of parents of the normal group, and similar

to those in the learning and behavioural problems

group. Parents of children with visual impairment

expressed more needs for future education and

school support than resources for dealing with

personal and family stress.

Conclusion: Service needs of children with visual

impairment and their families are high, particularly

for future education and school support. More study

on the various modes of accommodation for children

with visual impairment and more collaborative

work among different partners working in the field

of rehabilitation will foster better service for these

children and their families.

New knowledge added by this

study

- Needs expressed by parents having children with visual impairment (VI) are significantly higher than those of parents of mainstream school children without special education needs, and similar to those of parents of children with learning and behavioural problems.

- Clinicians have to be sensitive to the service needs presented by children with VI and their families. More collaborative work among different partners working in the field of rehabilitation will foster better service for children with VI and their families.

Introduction

Parents of children with developmental difficulties

face many challenges with child handling and

coping with school. In helping these children, the

needs of their caretakers should not be ignored.

Besides, better understanding of the needs of their

parents could shed light on the desired direction of general service planning, and enable optimal

use of our resources. The formulation of service

needs in collaboration with parents instead of only

by the health care professionals helps to facilitate

efficient family support implementation. This can

also serve as pre-intervention measurement for

reliable outcome evaluation.1 Child Assessment Service (CAS) of the Department of Health

comprises multidisciplinary professionals and

provides comprehensive developmental assessment

and rehabilitation prescriptions to children with

developmental and behavioural problems in Hong

Kong. Recently, CAS developed a Service Needs

Questionnaire (SNQ) to examine the needs of

parents of children with learning and behavioural

problems including dyslexia and attention-deficit

hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The scale has

undergone formal procedures of scale validation and

standardisation, and can be used as a reliable tool

for mapping the needs of parents with children with

different developmental disabilities.2

Although many studies have investigated

service needs of disabled children,3 4 5 few have

attempted to investigate service needs of children

with visual impairment (VI) and their families. The

parents’ perceived needs based on ethnicity, and the

degree of vision loss in toddlers from Latino and Anglo

backgrounds were reported based on qualitative

description. The future of their children was the

universal concern among parents. Other concerns

were household finances, adequacy of services, and

the impact on siblings. The perceived insensitivity

and lack of information from professionals were

sources of difficulty and frustration.6 On studying the perspective of parents of children with VI, it was

noted that many experienced difficulties, frustration,

and concerns about the child’s future; there was also

lack of helpful information, social isolation, and

inadequate support from school and community.7

Parents of children newly diagnosed with VI and/or

ophthalmic disorders in a tertiary level centre had

a tendency to identify information as their greatest

need, almost irrespective of the amount or type

actually provided.8

In the local setting, there are limited needs

analysis studies on disabled children, and none

targeted towards children with VI in mainstream

schools. In Guangzhou, however, focus group

interviews were conducted in a qualitative study to

elicit the experiences of 23 Chinese parents in caring

for their children with developmental disability who

were residents of the Mental Retardation Unit in a

Maternal and Children Hospital. Five categories

of needs were identified: parental, informational,

attitude towards the child, coping, and support.9

In Hong Kong, the Education Bureau

encourages students with diverse learning needs

to receive appropriate education alongside their

peers so as to help them develop their potential.

While special schools cater for children with

significant developmental disabilities, children with

milder developmental disabilities are integrated

into mainstream schools. In mainstream schools,

students have diverse special education needs (SEN).

Most have learning and behavioural problems, and

few have physical and/or sensory problems. This

study is the first local attempt to use a validated

and standardised psychometric tool to identify

the specific needs of parents of children with VI

studying in mainstream schools. The study also

attempted to examine if their needs are different

from those of parents of children without SEN

studying in mainstream schools and parents of

children with learning and behavioural problems.

Better understanding of the parental needs will help

in planning for future service and support for these

children and their families.

Methods

Participants and recruitment procedures

Parents of children with visual impairment

Child Assessment Service of the Department

of Health provides comprehensive assessment,

rehabilitation prescriptions, and management

services to children and families in Hong Kong. In

2012, the number of referrals served by CAS was

8773 with children aged below 10 years accounting

for 98.4% of the referrals (written communication,

CAS, 2013). The number of children aged below 10

years was estimated to be 252 100 in Hong Kong in

2012.10 Between 2006 and 2010, the number of newly diagnosed visually impaired children in CAS ranged

from 28 to 37 every year.11

Parents of 30 children with VI who were

studying in mainstream schools and who underwent

assessment by optometrists at CAS between May

2009 and June 2010 were recruited to participate

in the study (VI group). The parents were asked to

reply once for each child. The purpose of the study

was clearly explained, and a consent form was signed

by each respondent. All 30 consented to participate,

but four failed to complete the questionnaire. The

analysis reported in this study was therefore based on data from

26 participants who completed the SNQ. The degree

of VI ranged from mild low vision to severe low

vision, according to the definition for the provision

of various rehabilitation services by the Hong

Kong Government.12 The visual acuity for mild low

vision was defined as from 6/18 to better than 6/60,

moderate low vision was from 6/60 to better than

6/120, and severe low vision was 6/120 or worse in

the better eye.

Parents of children with behavioural and learning

problems

Parents of children with learning and behavioural

problems were recruited from two local parent

support groups (LB group). Parent support group is

a self-help organisation which serves the common

interests of parents having children with same or

similar disability or disease. Behavioural and learning

problems are the major SEN concern in mainstream

schools. In Hong Kong, there are a number of parent

support groups for parents having children with

learning and behavioural problems. Two parent

support groups, the Hong Kong Association for AD/HD and the Hong Kong Association for Specific

Learning Disabilities, were invited to participate

in this study as apparently they have the biggest

membership and the longest history in serving children with such developmental problems and

disability. All parents attending their annual meetings

were invited to participate on a voluntary basis, and

45 participated. A letter stating the purpose of the

study was given and a consent form was signed by

each respondent. The analysis reported in this study

was based on the 43 participants who completed the

SNQs. Despite the constraint of such convenience

sampling, efforts have been paid to enhance the

representativeness of the selected participants.

Parents of mainstream school children without

special education needs

Anonymous raw data of parents of children attending

mainstream primary schools (n=233) collected in

Leung et al’s study for the development of SNQ was

accessed and analysed.2 Three primary schools, one

each from the territory’s administrative regions,

were requested to randomly select 135 students to participate using a random number generator. The

schools distributed the questionnaires to parents;

246 parents returned the questionnaires in sealed

envelopes (response rate 60.7%) and 233 provided

complete data. Among the 233 participants from the

primary school group, 33 with reported behavioural/learning difficulties were excluded, and 200 were

included in the comparison (normal group). Since

SNQ was jointly developed by CAS and Leung et al,2

the research data were archived and shared between

the two parties. Upon an agreement between CAS

and Leung et al,2 the research data were retrieved

and analysed by authors. Legitimacy of such

arrangement was documented in the research

protocol written for SNQ project. The data retrieved

and being analysed for this study included SNQ

scores and demographics of participants.

Measures

Participants of the VI group and LB group were asked

to complete the SNQ and a questionnaire on the

demographics of the children and their responding

parents. The VI group was asked 12 additional

questions about the children’s ability to cope and

function in academic and recreational activities.

Service Needs Questionnaire

Service Needs Questionnaire had 27 items. It was

sub-divided into two parts, and was self-administered

by the informants. The first part

consisted of eight items on personal and family stress.

Participants rated each item on a 5-point scale from

1 (disagree very much) to 5 (agree very much). The

second part consisted of 19 items on need for various

services. Participants rated each item on a 5-point

scale from 1 (do not endorse at all) to 5 (endorse a

lot). This scale has been validated for use in Chinese

parents.2 The areas of need which can be identified

by SNQ included the need for school support, need

for information, and need for support on family

functioning.

This questionnaire was developed among

Chinese families and it showed satisfactory

psychometric properties.2 For validity, the SNQ total

score (5 categories) correlated positively (correlation=0.55) with Parenting Stress Scale, and it could

differentiate between parents of children diagnosed

with learning/behavioural problems and those

attending normal primary schools (t(336)=12.07;

P<0.001; d=1.42). For internal consistency and reliability, the reported Cronbach’s alpha was 0.96 and

intra-class correlation was 0.76, respectively. In

Leung et al’s study,2 Rasch analysis was conducted

to demonstrate the primary psychometric properties

of SNQ. It was shown that SNQ measured a single

construct need (ie unidimensionality); was able

to distinguish strata of needs in children with

developmental disabilities; had sufficient items to capture needs of children with developmental

disabilities; and there was a meaningful item

hierarchy. Construct validity and reliability of

SNQ were also shown by additional analyses.

As SNQ serves to describe needs of children

with developmental disabilities, the reported

psychometric properties were sufficient to serve this

aim.

Ability of a child to cope and function in academic

and recreational activities

There were 12 additional questions designed to

obtain some descriptive information from VI group

on children’s functional needs, school coping, and

difficulties encountered in academic and recreational

activities. Participants were asked to report positive

or negative answers regarding each question and

requested to give examples if the answers were

positive. Some examples of these questions were:

“Which is the most difficult subject for you? Please

state problems encountered, if any”; “Are there any

problems encountered in recess or lunch time? If

yes, please state the problem and the reason”.

Demographic information

Participants were requested to supply demographic information about themselves and their children.

The study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of the Department of Health, Hong

Kong SAR Government.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics, frequency distribution,

and means were used to examine the profiles of

participants. Since Leung et al’s study2 showed

difference among parents of children with learning

and behavioural problems and those of normal

children, our hypothesis was that there was a

difference between the needs of parents of VI group

and those of normal group. The data were examined

before hypothesis testing so that appropriate

statistical tests could be applied. Independent t test

and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were

used to analyse the differences in means between

two or more than two groups if the corresponding

test assumptions were fulfilled. Otherwise, Kruskal-Wallis test was used to analyse the differences in

mean rank for comparison of more than two groups.

The statistical analyses were performed using the

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Windows

version 19.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US).13 Statistical

significance was set at P<0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

Characteristics of participants

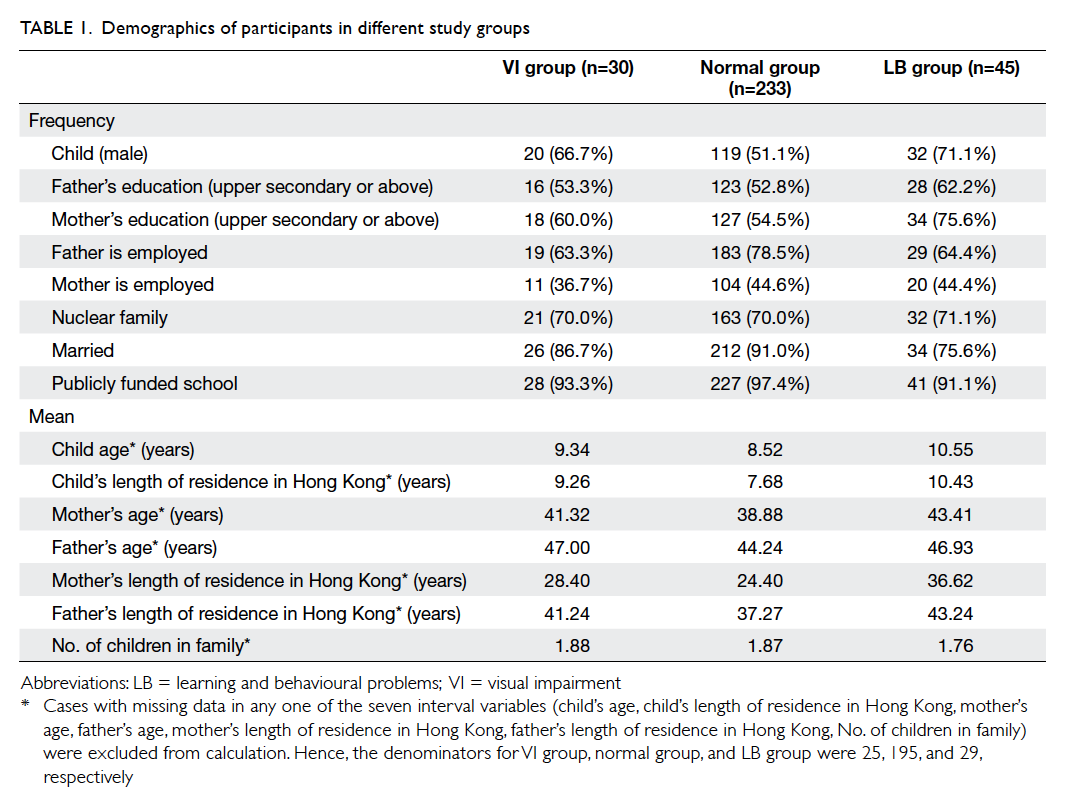

The demographic characteristics of parents in the

three groups were comparable. Compared with the

normal group, a higher proportion of boys were noted in VI and LB

groups and the mean age of children in LB and VI

groups was slightly higher. The parents of LB group

and VI group resided in Hong Kong for longer than

those of the normal group. Fewer fathers of LB and

VI groups were employed compared with those of

normal group (Table 1).

Intragroup comparison of Service Needs

Questionnaire in visual impairment group

Within the VI group, 26 participants with completed

SNQ data were included in the analysis. The most

common medical cause for VI was ocular or

oculocutaneous albinism (n=10). Other causes

included cataract (n=3), retinopathy of prematurity

(n=2), aniridia (n=2), retinal dystrophy (n=2), septo-optic

dysplasia (n=1), high refractive error (n=1), and

intraventricular haemorrhage (n=1); investigation

results were still pending for four cases.

Their cognitive abilities were mostly within

the low average to high average range. One had mild

mental retardation, two had limited intelligence,

and one had superior intelligence. Regarding co-morbid

developmental disabilities, 11 (42%) children

in the VI group had one or more than one type of

developmental disability apart from VI. One had

mild-grade mental retardation, four had dyslexia/risk for dyslexia, two had ADHD, one had autistic

spectrum disorder, two had mild hearing loss,

and one had mild anxiety problem. There was no

significant difference in SNQ total score between

those with or without co-morbid conditions (t(24)=

–0.6, P>0.05). The mean SNQ total scores for those

with and without co-morbid conditions were 94.93

(95% confidence interval [CI], 80.34-109.53) and

100.73 (95% CI, 86.51-114.94), respectively. Among

the 26 VI children, 18 had mild low vision and 8

had moderate-to-severe low vision. There was no

significant difference between the two levels of VI in

SNQ total score (t(24)= –1.425, P>0.05). The mean SNQ total score for those with mild low vision was

93.00 (95% CI, 79.55-106.45), and 107.25 (95% CI,

98.03-116.47) for those with moderate-to-severe low

vision. Therefore, all 26 cases could be treated as a

group for further analysis.

Reliability of Service Needs Questionnaire in

visual impairment group

The internal consistency of SNQ (Cronbach’s alpha=0.96) measured in the VI group was similar to the

magnitude reported in Leung et al’s study,2 despite

the difference in the samples used.

Comparison of service needs among normal

group, visual impairment group, and

behavioural and learning problems group

Owing to non-normality of the SNQ total score by

group, the Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA by ranks

was conducted to examine if the mean rank SNQ

total scores among the three groups were the same.

The Dunn-Bonferroni tests were further applied to

locate where the differences existed if the mean rank

SNQ total scores were not the same.

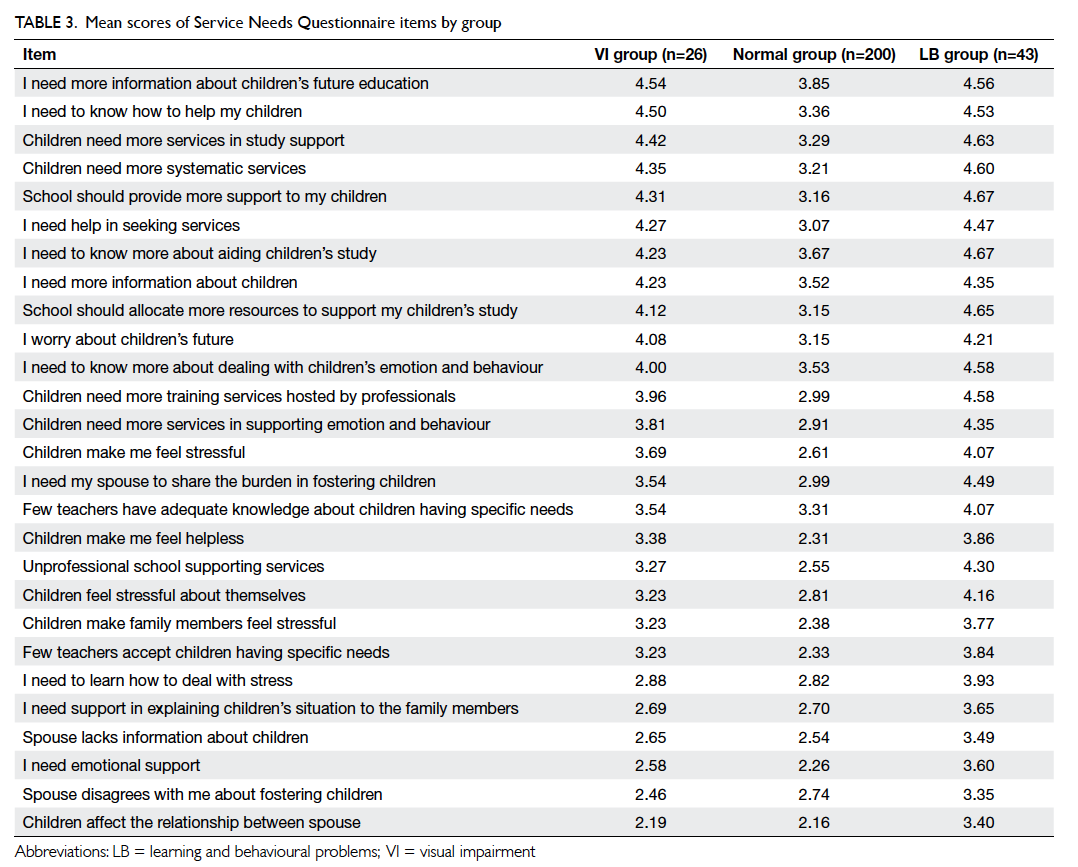

The Kruskal-Wallis test was significant (χ2(2)=80.928, P<0.001) inferring that the mean rank

SNQ total scores were not the same among the three

groups. The Dunn-Bonferroni tests showed that

the mean rank SNQ total score of the normal group

was significantly lower than that in VI group (z=

–4.042, P<0.001) and LB group (z= –8.531, P<0.001),

respectively. The mean rank SNQ total score of VI

group was slightly lower than that of the LB group, but

the difference was not significant (z=

–2.380, P=0.052; Table 2). Each SNQ item was

further analysed by conducting Kruskal-Wallis test

to examine if there was a difference among the three

groups. Bonferroni correction was applied to control

the family-wise type I error predefined as 0.05. All

SNQ items had significant differences among the

three groups.

Table 2. Kruskal-Wallis test of mean rank Service Needs Questionnaire total score and the multiple comparisons

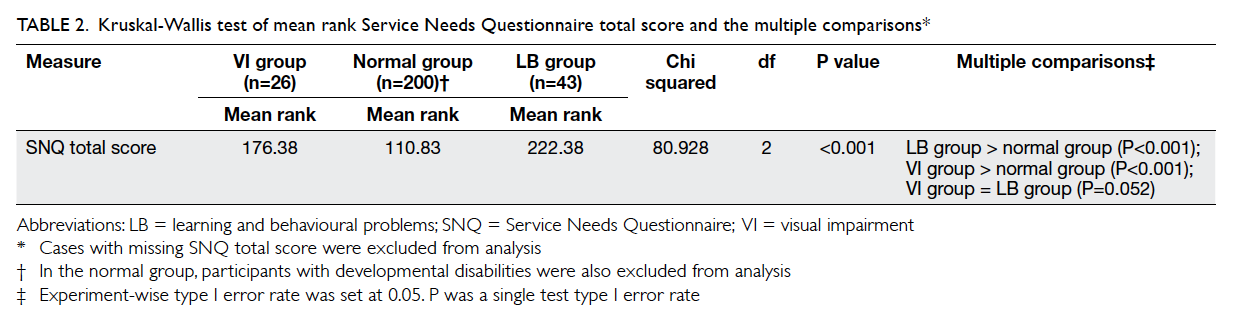

Eight of the top 10 needs were common to the

three groups. In the VI group, three of the top five

needs included education, services in supporting

study, and school support. For most SNQ items, the VI group scored significantly higher than the normal

group but similar to the LB group. For a few items

such as “I need to learn how to deal with stress”, “I

need emotional support”, and “Children affect the

relationship between spouse”, the VI group scored

significantly lower than the LB group but similar to

the normal group. On the item “Spouse disagrees

with me about fostering children”, the VI group had

lower score compared with the normal group. The

mean scores of each SNQ item are listed in Table 3.

Coping and functioning in academic and

recreational activities

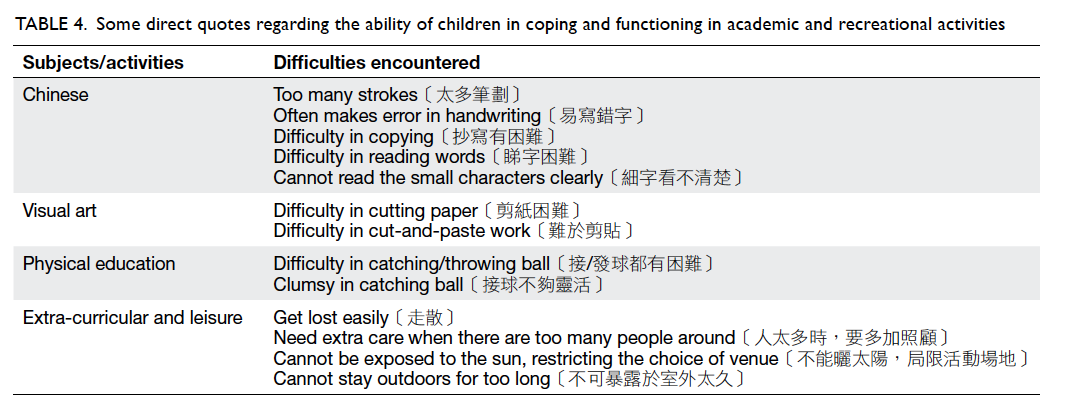

Regarding coping in school and functioning in

academic activities, most of the children with VI were

receiving some form of school accommodation and

support. The support included seating arrangement

(n=25, 97%), enlargement of font size (n=18, 70%),

assistance by peers in copying work and classroom

activities (n=7, 27%), and use of visual aids and assistive devices (n=3,12%). Physical exercise and

mathematics were reported as the most favourite

subjects, while Chinese and English were the most

difficult subjects for these children.

All children reported encountering difficulties

during classroom activities; examples included

difficulties with handwriting, reading, reading

comprehension and memory, ball games, as well as

cutting and pasting activities. Besides difficulties

encountered during class, around one-fifth (n=5)

reported encountering difficulties during recess or

lunch time due to lack of friends and peers to play

with and difficulties in attending outdoor activities.

Many (n=16, 62%) had joined some form

of extra-curricular activities, both indoor and

outdoor. Swimming, dancing, ping-pong ball, and

drawing were some examples of their favourite

activities. Some of the difficulties described were

problems with sustaining the practice, visual motor

coordination, communication with classmates, and classmates playing tricks on them. Around one-third

(n=8) reported difficulties in leisure activities during

school holidays, including the need for extra care

in crowded areas, extra protection when exposed

to sunlight, and some behavioural problems such

as talking loudly and offending other children. A

majority of them (n=20, 77%) did not join any self-help

parent group as many did not feel the need,

and most could not afford the time to join. Some

descriptive answers on the difficulties encountered

are listed in Table 4.

Table 4. Some direct quotes regarding the ability of children in coping and functioning in academic and recreational activities

Discussion

Vision is our major sense and children with VI

face many challenges and obstacles. In this study,

needs expressed by parents having children with

VI were significantly higher than those of parents

of mainstream school children without SEN. The

top five needs expressed by parents of VI children

are on need for information and services. In

particular, these parents expressed the need for

more information and services on future education

and school support despite receiving some degree of

accommodation at school. This may be related to the

general phenomenon among parents in Hong Kong

who predominantly focus on academic achievement

versus recreational and leisure activities. Meanwhile,

these parents might not be fully aware of the kind of

support available at school. The implication is for us

to work closely with the education sector to make

the school support service more transparent for the

parents. By maintaining necessary case monitoring,

we could give continuous feedback to the school

based on a child’s individual and changing needs.

Needs expressed by parents in the VI group

were significantly higher than those in the normal

group, but similar to those in the LB group. Children

with VI, in addition to their unique obstacles in

mainstream schools, also face some common

difficulties of adapting and adjusting academically,

socially, and behaviourally just like other children with SEN. Compared with parents of the normal

group, parents of the VI group perceived more

stress and, thus, more needs. Besides, nearly half the

children in VI group had co-morbidities, including

learning and behavioural problems. They might

experience similar challenges at school leading

to similar impact on their parents and families as

those in the LB group. Despite the insignificant

group difference between the VI and the LB groups,

we noted that more parents from the LB group

endorsed items related to stress, emotions, and effect

on relationship with spouse from the item analysis.

From this, it is believed that parents of the VI group

might experience relatively less stress and turmoil

resulting from children’s learning and behavioural

challenge as compared with the LB group. As

children with VI are often diagnosed at an early age,

it is speculated that their parents might have better

adjustment and more mutual support in caring for

them.

There were some limitations in this study,

including the small sample size. As compared to

the other developmental disabilities, the incidence

of VI was relatively low, affecting 0.1% of the school-age

population and 0.4% of children with all

developmental disabilities.14 In Hong Kong, most

children with significant developmental disabilities,

including those with severe low vision or blindness,

receive education in special schools. Children with

milder developmental disabilities, including those

with mild-to-moderate low vision, are integrated in

mainstream schools with support from teachers and

special schools. According to the statistics provided

by the Education Bureau, the total number of school

children with VI attending mainstream primary

schools was 40 in year 2006/07, 40 in 2007/08,

and 50 in 2008/09. The 30 cases in this study were

recruited from different regions of Hong Kong

during the study period and this cohort, therefore,

represents the majority of children with VI attending

mainstream schools in Hong Kong.

On the other hand, the VI group was not a

homogeneous group and nearly half had other

co-morbid conditions, which are common among

children with VI. The VI group with co-morbidities

is expected to express greater needs. However, this

was not observed in our study, probably due to the

small sample size. The other limitation might be the

possible self-selection bias in data collection. As

voluntary participation was sought in the LB group,

parents with high service needs might have been more

eager to participate, leading to bias. The normal

group was selected by convenience sampling, and the

grade, age, and gender distributions of the sampled

subjects in each school were not matched with those

of all students in each school. This normal group

might not represent all the mainstream primary

schools.

Currently, the Education Bureau provides

educational support for these children through

school teachers, with resource help from special

schools for VI children. Support includes assistive

facilities and visual aids, accommodation in school

activities and examination. It is encouraging to

note that these children are enjoying a variety of

extra-curricular activities despite the difficulties.

Nonetheless, more facilitation of peer support and

school integration is needed for these students both

during classroom and extra-curricular activities.

As most of these children should have needed

visual aids and assistive devices to optimise their

residual vision, the user rate noted was far below our

expectation. More systematic work on education

and training for parents will be needed to empower

them with the knowledge and skills for helping

their children, and to raise their awareness of local

community resources. On the whole, parents are less

aware of the availability of self-help support groups.

Fostering and encouragement of parent support

groups would be beneficial to the advocacy and

support of rehabilitation planning for children with

VI.

In this study, the needs of parents of children

with VI in mainstream school were measured using

a standardised and validated tool. With a relatively

low incidence of children with disability, and the

nature of common co-morbid conditions, it would be

beneficial to have pooled data from different regions,

including the education and hospital sectors, to shed

more light on the future planning of support services

for these children and their families. More study on

the various modes of accommodation for children

with VI and more collaborative work among different

partners working in the field of rehabilitation will

foster better service for these children and their

families.

Acknowledgements

Our special thanks to Dr Cynthia Leung for her

critical reading and Mr Morris Wu for the statistical

analysis and technical editing. We would like to

express our gratitude to all the parents who have

participated in this study.

References

1. Hendriks AH, De Moor JM, Oud JH, Franken WM.

Service needs of parents with motor or multiply disabled

children in Dutch therapeutic toddler classes. Clin Rehabil

2000;14:506-17. CrossRef

2. Leung C, Lau J, Chan G, Lau B, Chui M. Development and

validation of a questionnaire to measure the service needs

of families with children with developmental disabilities.

Res Dev Disabil 2010;31:664-71. CrossRef

3. Rosenbaum PL, King SM, Cadman DT. Measuring

processes of caregiving to physically disabled children and

their families. I: Identifying relevant components of care.

Dev Med Child Neurol 1992;34:103-14. CrossRef

4. Sloper P, Turner S. Service needs of families of children

with severe physical disability. Child Care Health Dev

1992;18:259-82. CrossRef

5. Nitta O, Taneda A, Nakajima K, Surya J. The relationship

between the disabilities of school-aged children with

cerebral palsy and their family needs. J Phys Ther Sci

2005;17:103-7. CrossRef

6. Dote-Kwan J, Chen D, Hughes M. Home environments

and perceived needs of Anglo and Latino families of

young children with visual impairments. J Vis Impair Blind

2009;103:531-42.

7. Leyser Y, Heinze T. Perspectives of parents of children who

are visually impaired: implications for the field. RE:view

2001;33:37-48.

8. Rahi JS, Manaras I, Tuomainen H, Hundt G. Health

services experiences of parents of recently diagnosed

visually impaired children. Br J Ophthalmol 2005;89:213-8. CrossRef

9. Wong SY, Wong TK, Martinson I, Lai AC, Chen WJ, He YS.

Needs of Chinese parents of children with developmental

disability. J Learn Disabil 2004;8:141-58.

10. Population by age group and sex, End-2012. Available

from: http://www.censtatd.gov.hk/hkstat/sub/sp150.jsp?tableID=002&ID=0&productType=8. Accessed 31 Oct 2013.

11. Lo PW. Children with visual impairment: experience

at Child Assessment Service (CAS). Child Assessment

Service Epidemiology and Research Bulletin. In press.

12. Hong Kong Government. White Paper on Rehabilitation:

Equal opportunities and full participation: A better

tomorrow for all. Hong Kong: HKSAR Government; 1995.

13. IBM Corp. Released 2010. IBM SPSS Statistics for

Windows, Version 19.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

14. Snyder TD, Tan AG, Hoffman CM. Children 3 through

21 years old served in federally supported programs for

the disabled, by type of disability: Selected years, 1976-77

through 2003-04. In: Snyder TD, Tan AG, Hoffman CM.

Digest of education statistics 2005 (NCES 2006-030). New

York: Institute of Educational Sciences; 2006: 81.