© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HKMMS

Halo-pelvic traction: a means of correcting severe spinal deformities

Louis CS Hsu, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)

Guest Author, Education and Research Committee, Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society

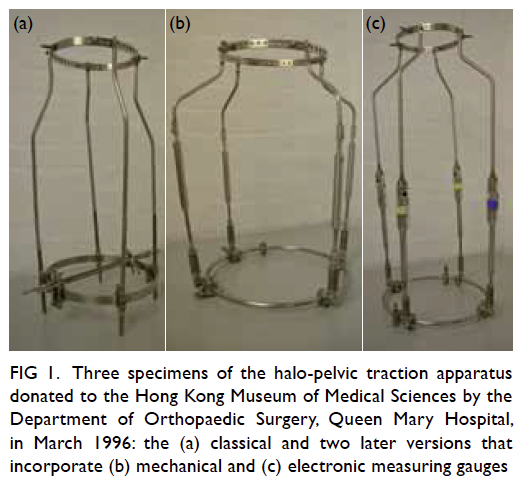

The ‘Halo’, a metal ring secured with four screws

into the outer dipole of the skull, was popularised by

Perry and Nickel in the 1970s for prolonged cervical

traction in place of the old-fashioned, two-screw

skull tongs used in cervical fractures. With pins

inserted into the lower femur, they devised the halofemoral

traction for correction of spinal deformities.

This proved to be inefficient and the femoral pins got

infected very easily. The patient also had to remain in

bed during the traction.

With extension of the Sandy Bay Convalescent

Home to become the Duchess of Kent Children’s

Hospital in the late 1960s, Prof A Hodgson, Prof

A Yau, and Dr J O’Brien developed the pelvic

attachment of the halo-pelvic traction (HPT) device.

The pelvic ring is secured to the two halves of the

pelvis by two threaded pins that traverse the whole

length of the two halves of the pelvis. Extension bars

fitted to the halo and pelvic rings provide fixation

and traction when the bars are gradually elongated.

The apparatus provided very powerful corrective

forces (Fig 1a). It also allowed the patient to remain

ambulant during treatment (Fig 2).

Figure 1. Three specimens of the halo-pelvic traction apparatus donated to the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences by the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Queen Mary Hospital, in March 1996: the (a) classical and two later versions that incorporate (b) mechanical and (c) electronic measuring gauges

Figure 2. Photographs of patients in the Duchess of Kent Children’s Hospital with the apparatus in situ

In the later stages of the HPT improvement,

gauges attached to extension bars were used to

measure the forces generated through the spine

and helped the surgeons to monitor and regulate

the speed of distraction. Initially, the gauges were a mechanical compression spring attached to the

bottom of the bars (Fig 1b). Later, electrical cells

were used and attached to the middle of the bars

(Fig 1c).

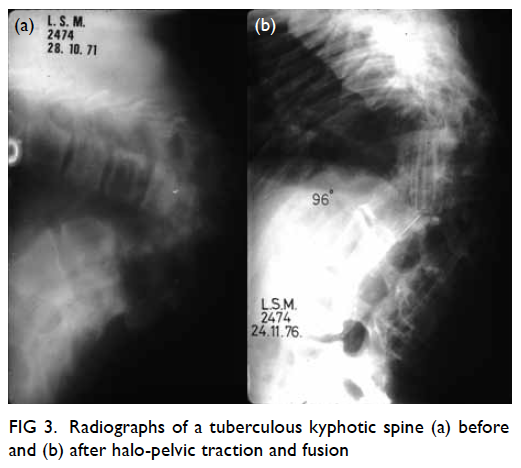

Halo-pelvic traction was ideal for the treatment

of severe and rigid spinal deformities such as healed

tuberculous kyphosis. The strong fixation allowed

osteotomies of the rigid deformity to be staged and

distraction forces to be gradually applied between

stages of surgery without fear of instability or spinal

cord compression (Fig 3).

Figure 3. Radiographs of a tuberculous kyphotic spine (a) before and (b) after halo-pelvic traction and fusion

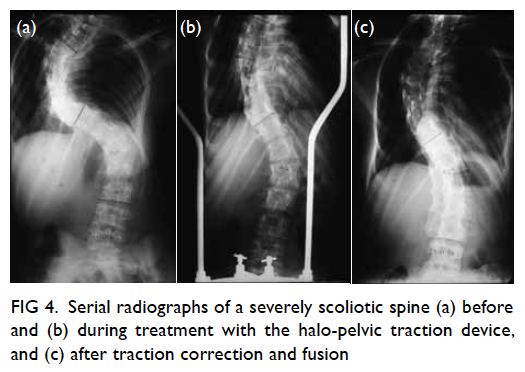

The apparatus can also be used for corrective

treatment of various types of severe scoliosis such

as that due to neurofibromatosis and poliomyelitis.

Again, the powerful distraction forces generated

can provide very dramatic correction of the rigid

deformities. Spinal fusions are performed after

correction of the deformities (Fig 4).

Figure 4. Serial radiographs of a severely scoliotic spine (a) before and (b) during treatment with the halo-pelvic traction device, and (c) after traction correction and fusion

Spinal tuberculosis and poliomyelitis epidemics

in Hong Kong in the 1950s and 60s left the region

with a significant number of patients with rigid spinal

deformities. Halo-pelvic traction came at the right

time as many patients could be appropriately treated

with this apparatus. Over 150 patients received HPT

treatment at the Duchess of Kent Children’s Hospital

during 1970 to 1982. All of them had severe spinal

deformities. They usually wore the apparatus for 3 to

6 months, and a few of them for up to a year.

However, the powerful distraction forces

along the spine, which houses the spinal cord, and

prolonged immobilisation resulted in some alarming

and unexpected complications.

During distraction, stretching the spine also stretches the nerves that run from the skull to the

trunk. The cranial nerves, especially the sixth,

tenth, eleventh and twelfth, and the brachial plexus,

especially the fifth and sixth nerve roots, can suffer

from traction injuries. In kyphotic patients, the spinal

cord may also be compressed by internal kyphus.

Detected early, these patients usually recover. Daily

neurological examination is an important routine in

managing the patients.

The cervical spine, being the most flexible part

of the spine, can be dramatically elongated by HPT.

The spinal cord may not keep pace. A small number

of patients with tuberculous kyphosis, despite a

gradual and slow distraction, suddenly developed

swinging temperatures and fluctuating rises in

blood pressure. These changes were attributed to

an early ‘coning’ of the medulla oblongata through

the foramen magnum, causing disturbances in the

temperature and blood pressure control centres.

These were quickly reverted by loosening the

distraction; the patients had no long-term effects

from these episodes.

An unexpected complication was discovered in

the odontoid process of the second cervical vertebra.

The blood supply to this process is essentially derived

from ligaments attached to this bone. With tension

in the ligaments from distraction, blood supply to the

odontoid process is jeopardised leading to avascular

necrosis. This was a rather common complication in

HPT. The necrosis itself recovered, but stiffness and

early degeneration of the cervical spine developed in

almost all of the patients.

Powerful traction to the flexible and fragile

cervical spine would cause minor damages to

the intervertebral ligaments and discs leading

to mild swelling, bleeding, and inflammatory

changes. Together with prolonged immobilisation,

spontaneous fusion had occurred in the cervical

spine in some patients.

With improvements in public health,

especially with infectious disease control and school

screening programmes for spinal deformities, severe

deformities requiring surgery are becoming rare. The

HPT device is now very rarely used, if at all, in Hong

Kong and in the rest of the world. Like many other

surgical instruments and equipment, it has become a

historical relic, though the service it provided to the

many deformed patients earns it a place in the Hong

Kong Museum of Medical Sciences.

References

1. O’Brien JP, Yau AC, Hodgson AR. Halo pelvic traction: a technic for severe spinal deformities. Clin Orthop Relat

Res 1973;93:179-90. CrossRef

2. Dove J, Hsu LC, Yau AC. The cervical spine after halo-pelvic traction. An analysis of the complications of 83

patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1980;62-B:158-61.

3. Yau AC, Hsu LC, O’Brien JP, Hodgson AR. Tuberculosis kyphosis: correction with spinal osteotomy, halo-pelvic

distraction, and anterior and posterior fusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1974;56:1419-34.