Hong Kong Med J 2014 Aug;20(4):285–9 | Epub 14 March 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134061

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Severe acute pyelonephritis: a review of clinical outcome and risk factors for mortality

Vera Y Chung, FHKAM (Surgery), FRCS (Edin);

CK Tai, FHKAM (Surgery), FRCS (Edin);

CW Fan, FHKAM (Surgery), FRCS (Edin);

CN Tang, FHKAM (Surgery), FRCS (Edin)

Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Pamela Youde Nethersole

Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr VY Chung (chungyeungvera@gmail.com)

Abstract

Objective: To review demographics of patients with acute pyelonephritis, their outcomes of severe upper urinary tract infection,

and to identify risk factors for long hospital stay and

mortality.

Design: Case series.

Setting: A regional hospital in Hong Kong.

Patients: Patients admitted between June 2007 and

June 2012 for acute pyelonephritis were identified.

Those with the most severe outcomes were analysed

of their mortality, need for care in the intensive care

unit, or necessitation of urological intervention.

Results: Overall, 68 patients fulfilled our criteria

for severe acute pyelonephritis. The female-to-male

ratio was 7:3. Their mean age was 58 years. Overall,

57% of the patients had impaired renal function

and 37% were diabetic; 47% developed shock after

admission and 56% required further intensive

care unit care; 75% of the patients demonstrated

radiological evidence of urinary tract obstruction

and required subsequent drainage procedures. Five

patients died due to severe acute pyelonephritis. The

prevalence of bacteraemia and bacteriuria was 57%

and 74%, respectively. Escherichia coli accounted

for the majority of causative organisms. Four risk

factors—bacteraemia, shock, need for

intensive care, and suppurative pyelonephritis—were associated with hospital stay of longer than 14

days. Old age (≥65 years), male sex, deranged renal

function, and presence of disseminated intravascular

coagulation were associated with mortality.

Conclusion: There was high prevalence of

bacteraemia and septic shock in patients with

severe acute pyelonephritis. The factors of old age

(≥65 years), male sex, deranged renal function, and

presence of disseminated intravascular coagulation

were associated with mortality. With the support

of intensive care, early recognition of urinary tract

obstruction and timely drainage, patients with

severe acute pyelonephritis generally carry a good

prognosis.

New knowledge added by this

study

- Contrary to the usual belief, the complexity of renal infections and septic shock were predictors for long hospital stay but not mortality.

- Escherichia coli still accounts for the majority of causative organisms in hospitalised patients with severe acute pyelonephritis.

- Early recognition of urinary tract obstruction and timely drainage are important in the treatment of severe acute pyelonephritis.

- Physicians could prevent potential mortalities by identifying those with risk factors and providing early intervention and intensive care.

Introduction

Acute pyelonephritis (AP) represents the most

severe form of urinary tract infection (UTI) and

is associated with significant morbidity and even

mortality. Approximately 250 000 cases of AP occur

each year in the US, with the incidence being higher

in women than men.1 The aetiological agent is

Escherichia coli in around 80% of the cases.2 Acute pyelonephritis has a quoted mortality of 10% to 20%.3

Several studies have identified a number of risk

factors for prediction of poor outcome, including

urinary tract abnormality, general debility, and

properties (ie virulence and resistance profile) of

microorganisms.4 5

The aim of this study was to review patient

demographics and outcomes of severe AP in a regional hospital, and to identify possible prognostic

factors for long hospital stay and fatal events.

Methods

Study design and data collection

We conducted a retrospective medical record review.

All patients admitted for AP between June 2007

and June 2012 to Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern

Hospital, Hong Kong were identified. Only patients

with the most severe outcomes were analysed

consecutively: (1) mortality, (2) need for care in

the intensive care unit (ICU), or (3) necessitation

of urological intervention. Patients suffering from

postoperative pyelonephritis were excluded.

The following data were collected: patient

demographics, presence of urinary tract obstruction,

presence of septic shock, need for intensive care,

modalities of urological intervention, bacteriologies,

length of stay, and mortality.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed by the Statistical Package

for the Social Sciences (Windows version 20; SPSS

Inc, Chicago [IL], US). A P value of less than 0.05 was

regarded as statistically significant. Chi squared test

and logistic regression analysis were performed. The

independent variables were patients’ demographic

and clinical data; the dependent variables were

mortality and long hospital stay (>14 days).

Results

Patient characteristics

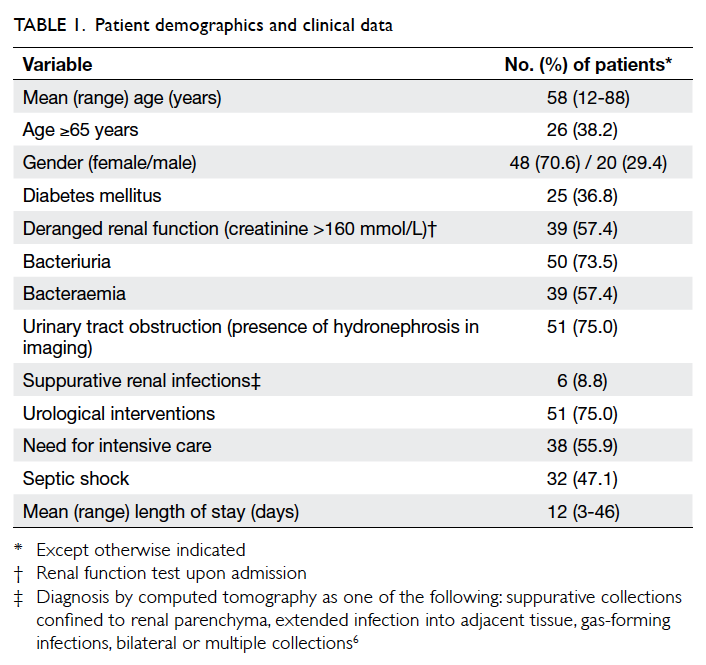

A total of 432 patients were admitted for AP from

June 2007 to June 2012. Of these, 68 patients fulfilled

our inclusion criteria for severe AP. Baseline patient

demographics, clinical characteristics, and imaging

findings are illustrated in Table 1.6 Overall, 75.0%

of the patients (n=51) demonstrated radiological

evidence of urinary tract obstruction, secondary to

stone (51.0%), ureteral stricture (5.8%), or extrinsic

compression (7.2%). Six patients had suppurative

renal infections, namely, renal abscess and

emphysematous pyelonephritis.

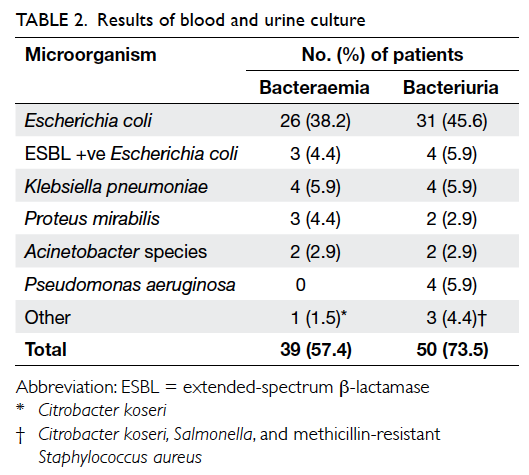

Microbiology

The yields of blood culture were positive in 57.4%

of the patients, with E coli being the commonest

causative organism (38.2%) followed by Klebsiella

pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, and Acinetobacter

species. Only three patients had bacteraemia caused

by extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing E coli

(Table 2).

The prevalence of bacteriuria was 73.5%,

and E coli accounted for the majority of cases

with bacteriuria, followed by K pneumoniae and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Table 2).

Urological procedure

In addition to antibiotic administration, 75% (n=51)

of the patients required urological interventions,

including percutaneous nephrostomy (n=41),

insertion of ureteric stent (n=5), percutaneous

drainage (n=1), and nephrectomy (n=5).

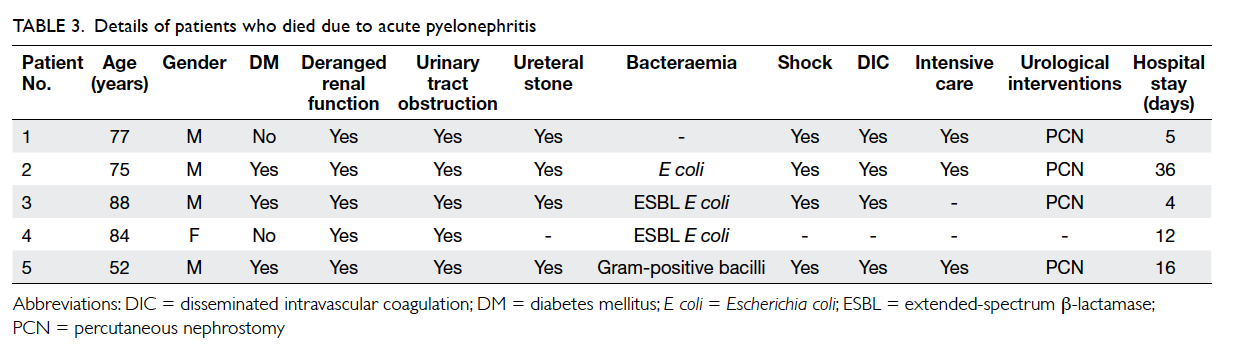

Mortality due to pyelonephritis

The overall mortality was 7.4% (n=5). Table 3

summarises the characteristics of patients who died

due to pyelonephritis within the same admission.

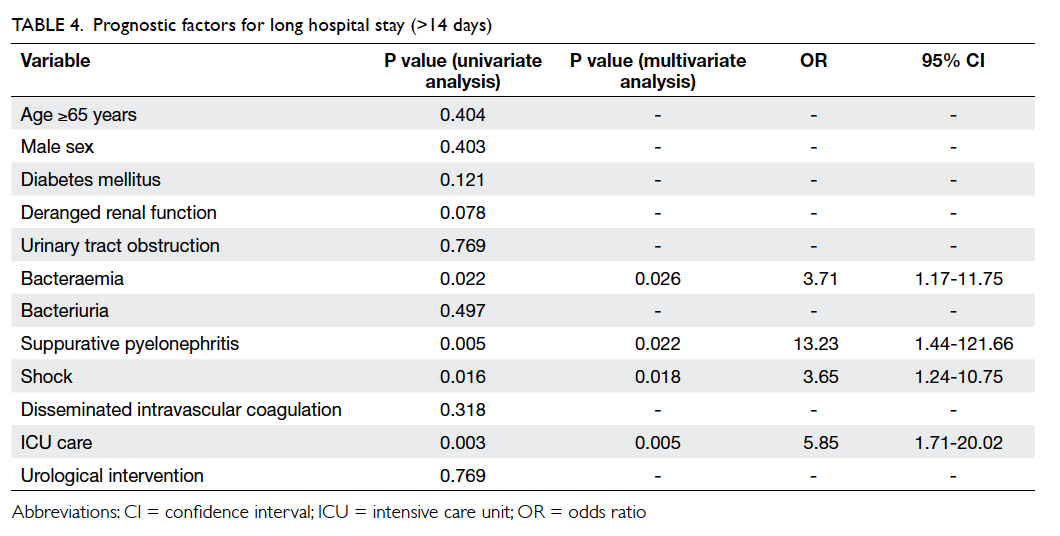

Prognostic factors for long hospital stay and

mortality

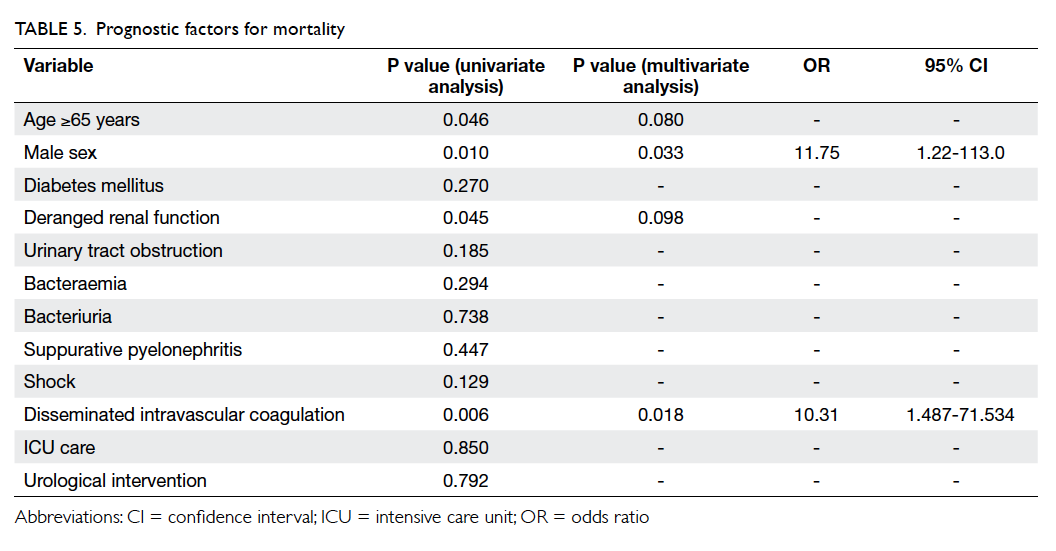

Risk factors for long hospital stay (>14 days; 32.4%)

and mortality (7.4%) were analysed (Tables 4 and 5).

Presence of bacteraemia (P=0.022), suppurative

pyelonephritis (P=0.005), shock (P=0.016), and need

for ICU care (P=0.003) were significant risk factors

for long hospital stay on univariate analysis. On

multivariate analysis, the odds ratios (ORs) were

3.71 for bacteraemia (P=0.026), 13.23 for suppurative pyelonephritis (P=0.022), 3.65 for shock (P=0.018),

and 5.85 for ICU care (P=0.005).

On univariate analysis, age of ≥65 years, male

sex, deranged renal function, and disseminated

intravascular coagulation (DIC) were predictors for

death. However, only male sex (OR=11.75; P=0.033)

and DIC (OR=10.31; P=0.018) were shown to be

independent risk factors in multivariate regression

analysis.

Discussion

Severe AP is an important disease entity that

frequently requires hospitalisation. Early recognition

of patients who are at risk of prolonged hospital stay

or even fatal events is important to improve treatment

results. Previous studies4 5 have shown a number of

risk factors including immunosuppression, old age,

and diabetes as risk factors for treatment failure. We

were interested in finding whether these risk factors

also applied to the local Hong Kong population.

An epidemiological study in the US found

that women are approximately 5 times more likely

than men to be hospitalised for AP; however, women

have a lower mortality rate than men.7 In our study

of hospitalised patients, females accounted for the

majority (70.6%) of AP cases. However, all but one

mortality from pyelonephritis occurred in the male

patients.

In one study on AP in adults, E coli was the

aetiological agent in 80% of the cases, but E coli

infections were less common in elderly patients

(60%). Furthermore, infections due to P mirabilis, K

pneumoniae, Serratia marcescens, and P aeruginosa

were very common due to the increased use of

catheters.2 Our study showed a similar microbial

spectrum. However, in AP, it is not always possible

to routinely document clinical UTI. This could be

attributed to previous antibiotic treatment, low

bacterial growth, or presence of atypical pathogens.8

In the present analysis, it was possible that a certain

proportion of patients had received antibiotic

treatment before admission to the hospital. Despite

this, the prevalence of bacteraemia and bacteriuria was relatively high (57.4% and 73.5%, respectively).

Escherichia coli accounted for the majority of

causative organisms.

An obstructed and infected kidney is a

urological emergency that may progress to septic

shock. Since acute obstructive uropathy raises the

renal pelvic pressure and, theoretically, decreases the

uptake of drugs by the kidney, emergency drainage

is warranted. A urological intervention significantly

increases the chances of good initial outcome.6 9

In this study, all patients who showed radiological

evidence of urinary tract obstruction were treated

with emergency drainage.

It has been suggested that bacteriuria and UTI occur more commonly in subjects with diabetes

than in the general population, and the risk of upper

tract involvement is also increased in these people.10

Diabetes seems to be associated with an increased

risk of severe UTI and unusual manifestations.11 12

The prevalence of diabetes in the present study was

also high (36.8%). In contrast with the results of

several studies, it was not shown to be a risk factor

for prolonged hospitalisation.4 5 The initial choice of

empirical antimicrobial therapy was not different

for diabetic patients, but we were more vigilant

for complications of UTI, such as emphysematous

pyelonephritis and abscess formation, in this group

of patients.

Recent reports4 13 have shown other risk

factors such as long-term catheterization and age of >65 years to be predictive of prolonged

hospitalisation. Our study revealed that four risk

factors—including bacteraemia, shock, need for

intensive care, and suppurative pyelonephritis—were associated with long hospital stay. These four

risk factors were closely related with and denoted the

most severe degree of pyelonephritis, thus resulting

in longer hospitalisation.

The mortality rate for patients with

pyelonephritis has been reported to be 1.2% to 33%.14 15

In our study, which included more severe group of

AP patients (ie those who required intensive care

or urological interventions), the overall mortality

rate was 7.4%. According to a previous study,4 septic

shock, bedridden status, age of >65 years, recent

use of antibiotics, and immunosuppression were

independent predictors of death. Another research

found that baseline health status of patients and

complexity of suppuration were the most important

predictors of clinical outcomes for suppurative

renal infections.6 In our analysis, patients who died

due to AP were predominantly older than 65 years,

presented with septic shock, and required drainage

for urinary tract obstruction. Among the risk factors

studied, age of ≥65 years, male sex, deranged renal

function, and DIC were associated with mortality

in univariate analysis. Additional multivariate

correlates were male sex and presence of DIC.

The limitation of the study was that the study

population consisted of a heterogeneous group

of patients and might not be representative of the

majority of uncomplicated AP cases. Presence of

resistant pathogens may contribute to treatment

failure, but we did not estimate this factor in our

analysis. Nevertheless, the outcomes of severe AP

also bear clinical implications for physicians who

mainly treat critically ill, hospitalised patients.

Conclusion

There was high prevalence of bacteraemia and septic

shock in patients with severe AP, with E coli being

the predominant causative organism. Male sex and presence of DIC were associated with mortality.

Early recognition of risk factors can potentially help

prevent death from severe AP.

References

1. Ramakrishanan K, Scheid DC. Diagnosis and management of acute pyelonephritis in adults. Am Fam Physician 2005;71:933-42.

2. Stamm WE, Hooton TM. Management of urinary tract infections in adults. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1328-34. CrossRef

3. Roberts FJ, Geere IW, Coldman A. A three-year study of positive blood cultures, with emphasis on prognosis. Rev infect Dis 1991;13:34-6. CrossRef

4. Efstathiou SP, Pefanis AV, Tsioulos DI, et al. Acute pyelonephritis in adults: prediction of mortality and failure of treatment. Arch Int Med 2003;163:1206-12. CrossRef

5. Pertel PE, Haverstock D. Risk factors for a poor outcome after therapy for acute pyelonephritis. BJU Int 2006;98:141-7. CrossRef

6. Stojadinović MM, Mićić SR, Milovanović DR, Janković SM. Risk factors for treatment failure in renal suppurative infections. Int Urol Nephrol 2009;41:319-25. CrossRef

7. Foxman B, Klemstine KL, Brown PD. Acute pyelonephritis in US hospitals in 1997: hospitalization and in-hospital mortality. Ann Epidemiol 2003;13:144-50. CrossRef

8. Rollino C, Beltrame G, Ferro M, Quattrocchio G, Sandrone M, Quarello F. Acute pyelonephritis in adults: a case series of 223 patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012;27:3488-93. CrossRef

9. Yamamoto Y, Fujita K, Nakazawa S, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for septic shock in patients receiving emergency drainage for acute pyelonephritis with upper urinary tract calculi. BMC Urology 2012;12:4. CrossRef

10. Stapleton A. Urinary tract infections in patients with diabetes. Am J Med 2008;113:80-4. CrossRef

11. Patterson JE, Andriole VT. Bacterial urinary tract infections in diabetes. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1995;9:25-51.

12. Lye WC, Chan RK, Lee EJ, Kumarasinghe G. Urinary tract infections in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Infect 1992;24:169-74. CrossRef

13. Roberts JA. Management of pyelonephritis and upper urinary tract infections. Urol Clin North Am 1999;26:753-63. CrossRef

14. Lee JH, Lee YM, Cho JH. Risk factors of septic shock in bacteremic acute pyelonephritis patients admitted to an ER. J Infect Chemother 2012;18:130-3. CrossRef

15. Yoshimura K, Utsunomiya N, Ichioka K, Ueda N, Matsui Y, Terai A. Emergency drainage from urosepsis associated with upper urinary tract calculi. J Urol 2005;173:458-62. CrossRef